One of the most hated government buildings in colonial Saigon, the Maison Centrale de Saigon (Khám Lớn Sài Gòn), or Saigon Central Prison, was a truly grim institution where thousands of unfortunates were incarcerated in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions.

Related Articles:

- Old Saigon Building Of The Week: Hồ Chí Minh City General Sciences Library

- Icons Of Old Saigon: Shophouse Architecture

- Icons Of Old Saigon: The Casino de Saigon

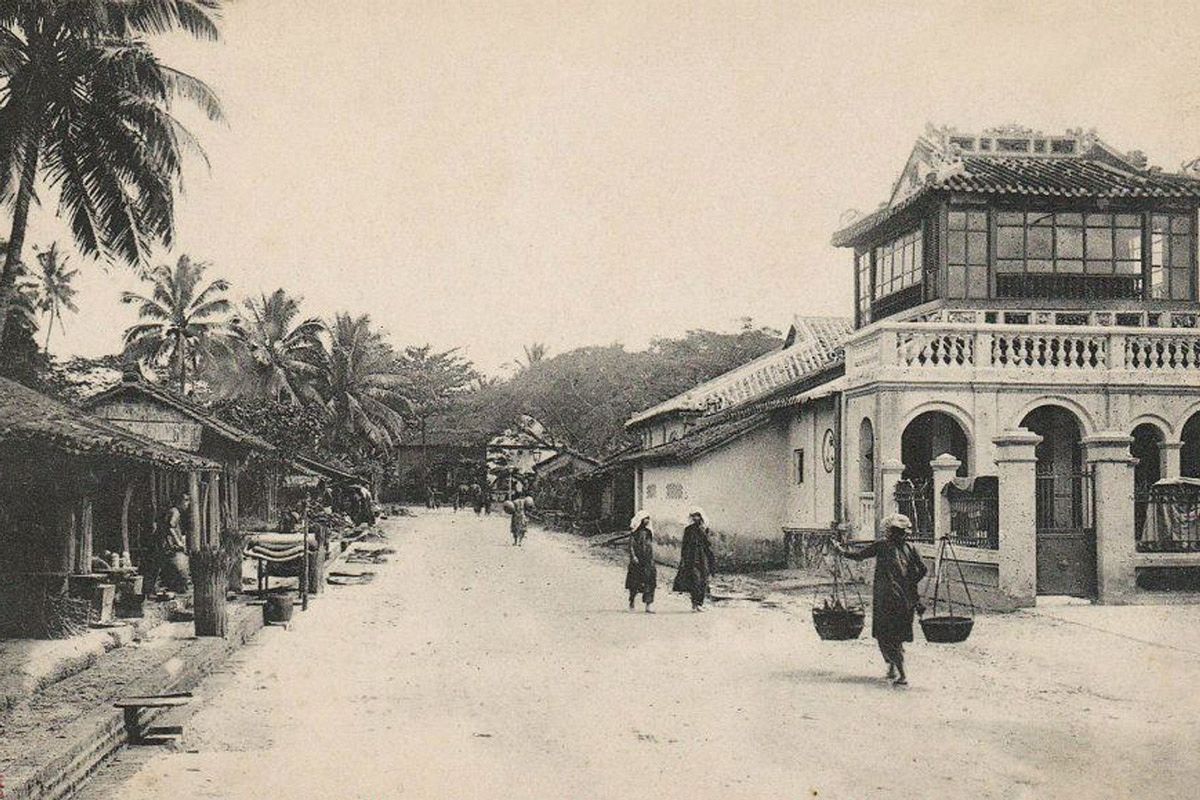

Noodle soup sellers opposite the Maison Centrale de Saigon

Originally built in 1865-1866 on the site now occupied by the Hồ Chí Minh City General Sciences Library, the Maison Centrale was enlarged in 1885 at the time of the construction of the adjacent Palais de Justice (Law Courts), “following a plan that met all the legal and medical requirements embodied in the theory and practice of the period,” according to a 1933 article published in L'Eveil économique de l'Indochine. The prison included “a central pavilion overlooking the rue de La Grandière incorporating the registry, archives and guards’ offices on the ground floor and staff housing on the upper floor”.

The Maison Centrale de Saigon pictured in the 1890s

After the 1885 reconstruction, the Maison Centrale's detention buildings comprised huge windowless three-storey blocks, built around a large front courtyard and two smaller rear courtyards. Political prisoner Phan Văn Hùm’s 1928 memoir Ngồi tù Khám Lớn (In Khám Lớn Prison) tells us that the cell walls and ceilings were painted black, and prisoners were forced to lie on the stone floor with their feet manacled. Prisoners on “death row” were accommodated in five-meter-long tubes built into the walls, accessed by steel grills.

Several reports from the late 1880s onwards describe the Maison Centrale as overcrowded and filthy, its inmates given insufficient food and overworked by excessive labour. One particular document from 1889 mentions over 900 prisoners, incarcerated in “deplorably unsanitary conditions”. Dampness and lack of light and ventilation contributed to poor hygiene, and deadly epidemics were commonplace.

During the 1880s and 1890s, many unfortunate inmates of the Maison Centrale fell victim to cholera and beriberi. Any prisoner suffering from these illnesses was immediately evacuated to Chợ Quán Hospital; according to one medical survey (Traité d'hygiène, Étiologie et prophylaxie des maladies transmissibles, 1912), during the period between July 14 and December 29, 1899, 213 of the 236 deaths at that hospital were due to beriberi and 195 of those who died came from the Maison Centrale de Saigon, “proving that living conditions were far from being secondary causes of the disease”.

The Maison Centrale de Saigon in its original form on the 1871 city map and after reconstruction on the 1896 city map

One of the biggest concerns for humanitarians of the era was the incarceration of minors in the prison. In his book Ma chère Cochinchine, trente années d'impressions et de souvenirs, février 1881-1910 (1911), George Dürrwell describes the “painful memory” of a professional visit to the Maison Centrale, where he found “10 children aged 12-15 years” incarcerated in “a dark cell of about 15 feet square entirely occupied by a huge camp bed”. These “small and unhappy children” had been sent for some minor offences to this “horrible slum”, where they would “vegetate” until they reached the age of 16.

He continues: “I might add that, in order to avoid the danger from adult prisoners, their hours of going outside were scrupulously measured, and it’s thus that these poor kids were usually confined to their cell.” Not until 1904, after Cochinchina Governor Rodier had given an impassioned speech about the dangers of mixing children with adults in the “promiscuity of the Maison Centrale”, did the French authorities finally begin to set up special facilities for young offenders.

Prisoners wearing the "cangue" inside the Maison Centrale

During the early years of the 20th century, the Maison Centrale witnessed numerous large-scale prison riots, the most serious being those of 1905 and 1914, when in each case several prison guards were killed. However, perhaps the most famous incident at the prison was the attack launched on the night of February 14, 1916 by a band of around 300 armed supporters of the Heaven and Earth Association (Thiên Địa Hội, 天地会Tiāndìhuì) in an attempt to free their leader Phan Xích Long (1893-1916). The attack failed; 57 attackers were killed and many others captured.

As early as 1905, the authorities made a public admission that conditions in the Maison Centrale were “not consistent with the principles of modern hygiene”, but in subsequent years nothing was done to deal with the problem.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the number of detainees increased steadily along with the growth of anti-colonial activity, compounding the problem of overcrowding and lack of sanitation. During this period, many Vietnamese revolutionaries were detained in the Maison Centrale and several were executed in the courtyard, including the early Communist activist Lý Tự Trọng (1914-1931), after whom the street outside the Hồ Chí Minh City General Sciences Library is now named.

Left: Phan Xích Long (1893-1916) - Right: Lý Tự Trọng (1914-1931)

According to a 1933 article in the Courrier de Saïgon newspaper, “Our prison, built a long time ago, was built to incarcerate just a few hundred prisoners. However, today there are more than a thousand housed there, living one on top of the other. The steady increase in the number of detainees at the Maison Centrale has obliged the authorities to install an annex at Phu-My, in a building belonging to the Saigon Botanical and Zoological Gardens. On average, another 350 prisoners are housed there.”

In July 1934, an article entitled “À bas les bastilles capitalistes!” (Down with the capitalist bastions!) in the French Communist Party newspaper L'Humanité claimed that as many as 6,971 prisoners were being held in the Maison Centrale.

The July 1934 article “À bas les bastilles capitalistes!” in the French Communist Party newspaper L'Humanité

With the number of detainees continuing to increase, the French authorities conceived a plan to build a much larger prison outside the city center. Reporting on this plan, an article in the May 1933 edition of L'Eveil économique de l'Indochine states: “Based on the information we have, the new Maison Centrale will be built through a loan on a plot of 16 hectares, located in the village of Chi-Hoa. It will accommodate 2,000, with special quarters for each category of prisoner, and even a hospital. What lucky prisoners!”

Yet, due to financial difficulties, the plan was shelved and conditions at the Maison Centrale continued to deteriorate.

The event which finally spurred the French authorities into action was the failure of the Southern Uprising (Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa) in November 1940. In the wake of this uprising, huge numbers of rebels were captured, obliging the French authorities to repurpose government offices as detention centers and even to rent hotels and other private buildings for use as temporary prisons!

Finally in December 1941, approval was given for the construction of the current prison in Chí Hòa (now District 10). At this time, Japanese forces were occupying Saigon and the new prison is said to have been designed by a Japanese military architect. Construction began in 1943, but due to administrative delays and the subsequent outbreak of the First Indochina War, Chí Hòa Prison was not completed until March 1953.

Chí Hòa Prison (Wikipedia photo)

Soon after Ngô Đình Diệm assumed power in 1955 as President of the Republic of Việt Nam, he drew up a plan to build a grand National Library building on the site of the old Maison Centrale. However, because of the prevailing political and economic situation, the project quickly ground to a halt. Consequently, the old prison survived as a temporary detention facility until 1968, when it was finally demolished to make way for the new National Library, now the Hồ Chí Minh City General Sciences Library.

Still in use today, the replacement Chí Hòa Prison was a three-storey octagonal structure designed in the shape of the bagua (八卦) or eight trigram symbol used in Taoist cosmology. Since 1953, it has acquired an equally fearsome reputation as a high-security detention facility – although in 1995 this failed to prevent the infamous Phước “Tám Ngón" (Eight-fingered Phước) from carrying out what was described at the time as “an unbelievable prison break”!

Hồ Chí Minh City General Sciences Library

Tim Doling is the author of the walking tours book Exploring Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2014) and also conducts 4-hour Heritage Tours of Historic Saigon and Cholon. For more information about Saigon history and Tim's tours visit his website, www.historicvietnam.com.