When you step inside the jewel-box-sized Nay Mai Tạp Hóa, you have no choice but to confront the immediacy of the products on display around you. Clothing, artwork, zines, jewellery, stickers, you name it, from local and international designers. The shop, which opened last year, fulfills the ‘anything-you-might-need’ role of its distinction as a tạp hóa; the Vietnamese equivalent to a corner store.

In addition to those that fall under the Soulvenir and Nay May labels, the store stocks a range of items from both Vietnamese and international designers.

Tân Nguyễn and his partner Ý chose to call Nay Mai a tạp hóa and not a boutique to underscore their casualness and intimacy. Your local tạp hóa is probably mere minutes from your door, and the staff likely knows you, maybe from your late-night penchant for potato chips or always forgetting your rain poncho.

When out in Saigon, it is often easy to spot people wearing Soulvenir and Nay Mai items.

The charm and familiarity of a corner store is probably not why you came to Nay Mai, though. Odds are you came for Soulvenir, the Vietnamese fashion brand that has become one of the most well-known both inside and out of the country. It explores the culture and history of Vietnam primarily through single-color screen prints that adorn garments. Their wearable designs are meant to be worn by anyone, with the idea that the wearer will feel both powerful and fashionable. The images and words are simple but striking and can easily catalyze a conversation. I’ve found that if I up my observation skills when out in Saigon, I see their pieces everywhere.

The now-iconic Việt Nam ball cap from Soulvenir.

When speaking about the brand to reputable local publications such as i-D and L'Officiel, Tân usually serves as the official spokesperson because the name Nay Mai originated in 2017 with a final project for his graphic design studies at Seattle Central Creative Academy. Today, the label is a joint effort of the couple.

While Tân is the one who referenced the story of Alice in Wonderland when I asked him about how he and Ý research and take inspiration for their designs, it is me who feels like Alice during the time I spent getting to know them and their trajectory from international students in America to Saigon-based designers, business owners, and parents.

Tân and Ý with their children Biển and Mây.

To best understand the creative sphere of this couple, both in profession and life, it’s smart to think about successful complements.

Tân and Ý

They are the fundamental complement. The evolution from close friends to college sweethearts to collaborators began after they both had moved, Tân from Saigon and Ý from Nha Trang, to the U.S. to attend high school. In addition to a shared interest in design, their similar experienes as foreign students and a shared native language and culture helped them forge a strong bond when they met while working the same part-time cafeteria job and attending classes where the cafeteria was housed – Seattle Central. Their bond only strengthened as they struggled, strived, and supported each other through college.

While students in the US, Ý (left) and Tân (right) visited New York City in 2017. Photo courtesy of Nai Mai.

Despite working full-time hours as full-time students and still being stressed about making tuition – Ý remembers lots of tears – they loved the well-respected Associate Degree program. It gave them the opportunity to explore their enthusiasm for fashion and layout with encouraging professors in an environment that let them play and experiment. It was there that they taught themselves the basics of screen printing on old, unused equipment and learned how to work together in the creative process.

Being raised around two generations of tailors means it’s hard to separate fashion from who Tân is. With a playful tone of jealousy, Ý explained how designing clothes comes naturally to him. “It’s so easy for him; he just knows how something is going to look.” She further explained that this stems from his research and appreciation of fashion, everything from that of his favourite hip hop artists to the reworked aesthetic of Belgian designer Martin Margiela. Tân was also a founder of the now-idling social media account VSSG – The Vietnamese Street Style Group – which highlighted fashionable young Vietnamese.

Tân and Ý (and baby Biển) screen printing at an outdoor market in the International District in Seattle. Photo courtesy of Nai Mai.

The vision for a jacket or a pair of shorts may come from Tân, but Ý is clearly the one who determines when something is finished. When they were preparing their first collection, Chapter 1: Lao Động, Tân’s parents, who had moved to America by then, offered as much guidance from afar as they could to help the couple understand patternmaking. Despite the help, there was still a lot of back and forth with the tailor they worked with. Ý explained that “normally, a tailor would provide two or three samples for a design. But we had boxes full of them.” Even when she “would drive him crazy needing things to be right,” they were made right. As much as Tân was upset they had to push back the release, he loved the final samples.

This exacting nature has extended to Ý’s idea to change the interior stitching on the shoulder seam on some recent T-shirts. It is finished in a way so that if you wanted to wear the shirt inside out, the seam would belie that. It is a thoughtful touch that not only acknowledges that people do wear their shirts inside out but also gives those who may have never, a new option.

Reflecting on the impact of their studies at Seattle Central, Tân said, “I can’t remember the specifics, but in class we would discuss how we have information that is always there. Like, I knew that Nay Mai would sell what it does even before seeing any of it.”

Ý continued, “You kind of always know what you’re going to do. It’s just in you, and you have to just do it. When I was doing the branding for the store, I didn’t have to go through the whole branding process. I closed my eyes and did it. I knew exactly what to do because it’s always been there.”

Tân, Ý, Biển, and baby Mây in Seattle a few months before they moved back to Vietnam. Photo courtesy of Nai Mai.

Nay Mai and Soulvenir

Even though the world met Soulvenir first, Nay Mai is the umbrella for all that they do – the “mother or soul” as Ý pointed out. Behind the little tạp hóa up front is their studio, where their ideas incubate and take shape. But Nay Mai also serves as a label that they design from. The name comes from a saying that you can see printed on the front doors, “Here Today, There Tomorrow.”

“Soulvenir is the connection with the cultural part of us, and Nay Mai is our playground,” Ý succinctly explained.

Nay Mai is also profoundly the soul because it is also their home, as indicated by the request to remove your shoes upon entering, The second floor is where they live. The property is actually where Tân grew up.

Tân shared that as his work has always been about his Vietnamese community and culture, it was important for him to be here, to return. After they both had finished college, including Tân’s further studies to receive a B.A. at Lake Washington University of Technology, they had tried to find design jobs in Seattle, but the market was tough. They were even able to open a proto-Nay Mai shop through a grant from the municipal government. It was called Không Gian (space) and sold Soulvenir t-shirts and hoodies. But then the pandemic, parenthood, and the recession. They felt stuck. In late 2022, they returned to Saigon.

Coming home gave them a chance to reconnect with friends and designers here. It also gave them a new opportunity to expand and better realize their designs. The easier access to materials and manufacturing partners “gave them the chance to create more things, to create more products, even just for the sake of being creative.”

“We want to present ideas that are not necessarily always Vietnamese, but that Vietnamese people can learn from and other people can exchange information from,” he further explained.

My first purchase from them was their Yêu (love) t-shirt, which includes lines from a Xuân Diệu poem. The sentiment soothed my perpetually longing heart. The message behind the shirt, though, was to either understand why Diệu also had such a heart or offer someone unfamiliar with him, like I was, an opportunity to learn why.

Front and back of the Yêu (love) t-shirt from Soulvenir includes lines from a Xuân Diệu poem.

With Soulvenir, they feel strongly about being responsible with how their designs connect to Vietnam, regardless of where the printed image or words might fall on a political spectrum. Each choice is thoughtfully considered for how and what it communicates.

Tân thinks the Việt Nam ball cap is the perfect middleground for their messaging. On the pure fun side, there is the Tôi Ko Phải Là DJ / I’m Not a DJ T-shirt. They’ve also done shirts that touch on more serious topics, such as Thích Quảng Đức, who was a Buddhist monk who self-immolated as a form of protest in 1963, or the war in Gaza.

Responsibility is underscored by their awareness of how such subjects will be received. “I always think about the message we’re putting out, political or not,” Ý explained,

The Hoà Bình Cho Trẻ Em (peace for children) design was created using an illustration from a Vietnamese poetry book for kids and their son Biển’s handwriting. It was made in reference to the war in Gaza.

“It has to make sense to us,” Tân continued. “The message has to be something we believe in. If we’re going to put something out there that’s more controversial, then we have to do it in an appropriate way.”

Their creativity is evident when they do so, such as with Gaza. Last year, they created an image with an illustration from a Vietnamese poetry book for children. Along the bottom was a message written in their son Biển’s handwriting: Hoà Bình Cho Trẻ Em (peace for children).

The designs that come under Nay Mai are for when they want to design for design’s sake. Unlike Soulvenir, they are not created with the idea of representing Vietnam’s history or culture, whether that’s because it’s something totally unrelated (such as an image from a film) or would be inappropriate (a bikini).

Movies, on that note, are a big part of their lives and can serve as inspiration for them in the same way that Vietnamese sign typography or the DIY aesthetic of the Seattle punk scene they were around can . A trip to the zoo can cause them to be struck by French colonial chairs from a century ago, and a trip to MUJI gives them appreciation for minimalism.

“Everything is inspiring to us,” Ý said. “We tell ourselves a product is good when function, form, and context are in balance. That is what we want to do with our designs.”

Ý holds the Bảo Vệ Tương Lai (protect our future) sign she designed. Its reference to a traffic sign is a straigtforward message about protecting children (the future). But the playfulness inherent is for those who know that children are often used in Vietnamese propaganda to signify the future of the country.

We returned to Alice going down the rabbit hole when I asked Tân how he finds old photos of Vietnam that regularly appear on the Soulvenir Instagram, their “visual moodboard.” He might search “1997 in Saigon,” and then be taken by a particular photographer, who he then searches for within Getty Images, which leads him to the photographer’s peers, which might lead him to gas stations of that era. It is an endless enjoyable journey for his curiosity and imagination.

Pride and Community

Tân and Ý share purely for the act of sharing and to connect with peers who do the same or appreciate what they see. The desire “to connect, recollect, and express our collective self beyond boundaries” is also part of how they officially describe Soulvenir, but it’s clear how this is the ethos of Nay Mai, too.

Connecting through experience and expression feeds into another of the store’s complements: an interplay between senses of pride and community. Tân and Ý believe there is a lot of good design happening in Vietnam right now, and they are eager to showcase what they can in Nay Mai. But for that to happen, Tân and Ý have to feel that they can speak for the designs, which, as previously mentioned, can be anything and everything.

When browsing the store, you might also find small treasures like messages from other designers or customers

“I want to be able to easily talk about the products,” Ý asserted, with Tân finishing her thought, “in the same way we can talk about our own.” This personal connection to each and every one of the makers and the ability to speak on their behalf sets them apart from similar stores in the city.

And when those products sell, Ý, especially beams with pride, “One of the highest compliments I received from a customer was that they could see how proud I was of what we have.”

Customers are both locals and tourists who learn of the designs through the couple's Instagram accounts and their international network of friends, peers, and clients

If you follow Nay Mai’s Instagram, you know how proud they also are of their community of customers. The daily stories contain photos of customers who visited and purchased that day. The smiles are wide as they show off Nay Mai’s sustainable rice bags that serve as shopping bags.

“Even if we only have one customer for the day, I’m proud to show them off. We’re nothing without our customers,” said Ý.

They feel that they are horrible at marketing, but their social media sharing and presence at maker fests, such as the regularly held LÔCÔ art market, are easy ways for them to create touchpoints that are genuine. Their customers are locals and tourists, especially those from afar who know of their designs through the couple’s network of friends, peers, and clients – the studio is also where Ý does her freelance layout work.

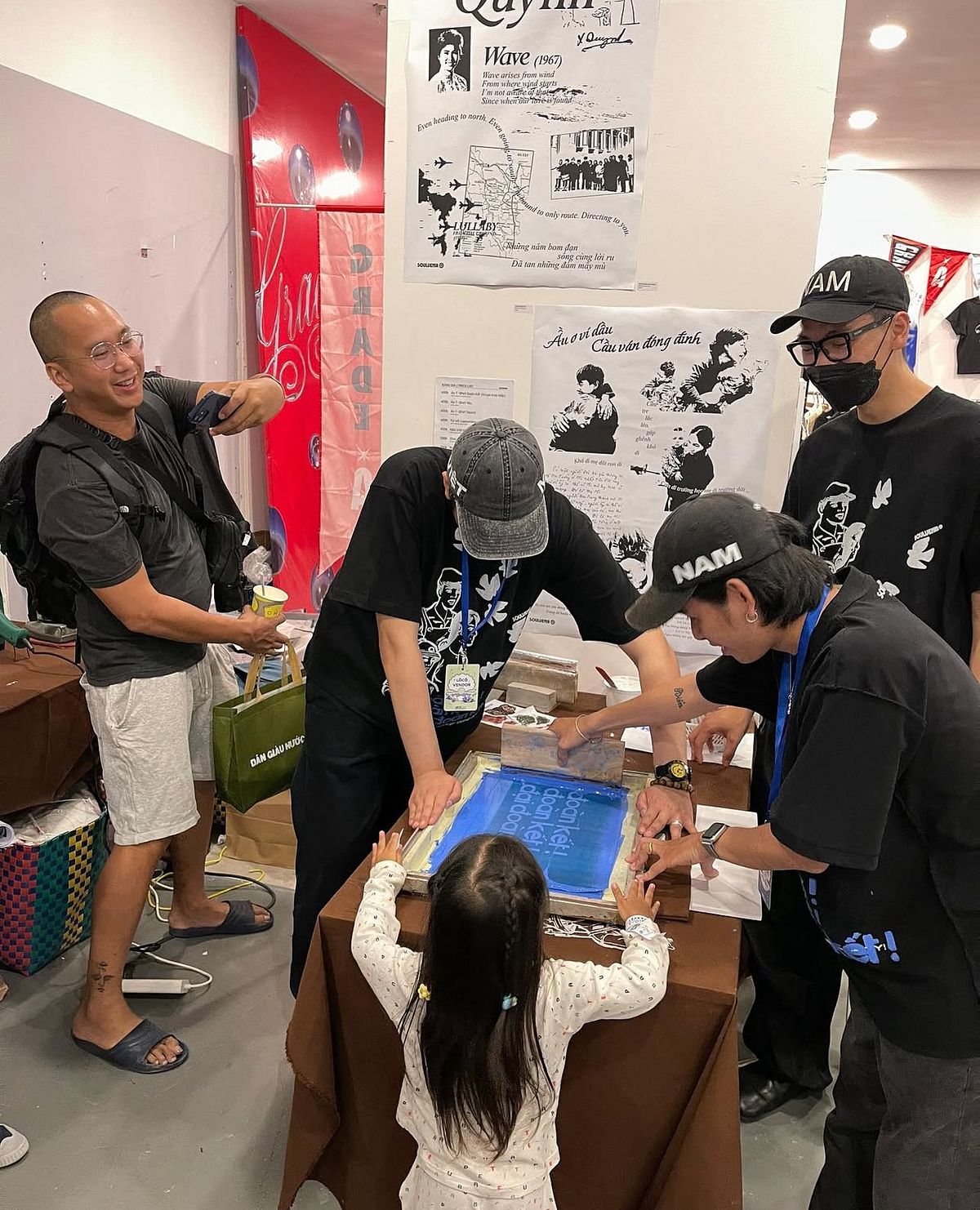

At Soulvenir's first appearance at a LÔCÔ art market since moving back to Vietnam, Tân (foreground, right) helps a little girl complete a screen print. Photo courtesy of Nai Mai.

Nay Mai represents all that Tân and Ý pursue with their work, but when speaking to them, it is clear that Biển and his little sister Mây represent the primary why at this moment. They are the ultimate source of pride. Both voice how the children’s wonder and excitement are endlessly inspiring, and how they’ve learned so much more about themselves from them and through parenting.

The children’s school tuition fees play a role in the already difficult financial challenges of running a small business – it’s like a third kid, Tân joked. They have to have enough capital to manufacture their products, which can be especially difficult at times because there is no wholesale-style business. If they don’t have enough because of something like the monthly fees, things get put on hold; things such as their latest collection or finding a new place to live so that they can expand the shop space. The goal of a more robust online shop will be easier to attain soon.

With Nay Mai as their home, the community that surrounds Nay Mai has always literally and figuratively been Tân’s community. It is now Biển and Mây’s, too. But for them, their childhood community includes the shop’s staff who have become extended members of their family, and the designers, friends, and customers whom they might meet when they’re not at school.

Tân and Ý’s faces light up when they talk of the kids’ interest in art and design and their curiosity about what they see in the shop or out in the world. They are clearly cultivating an appreciation of visual communication, maybe even for a future generation.

Tân and Ý drive forward.

When Tân was explaining how his designs are always, already, in him, he told me that “everything we do is a prototype of the next thing.”