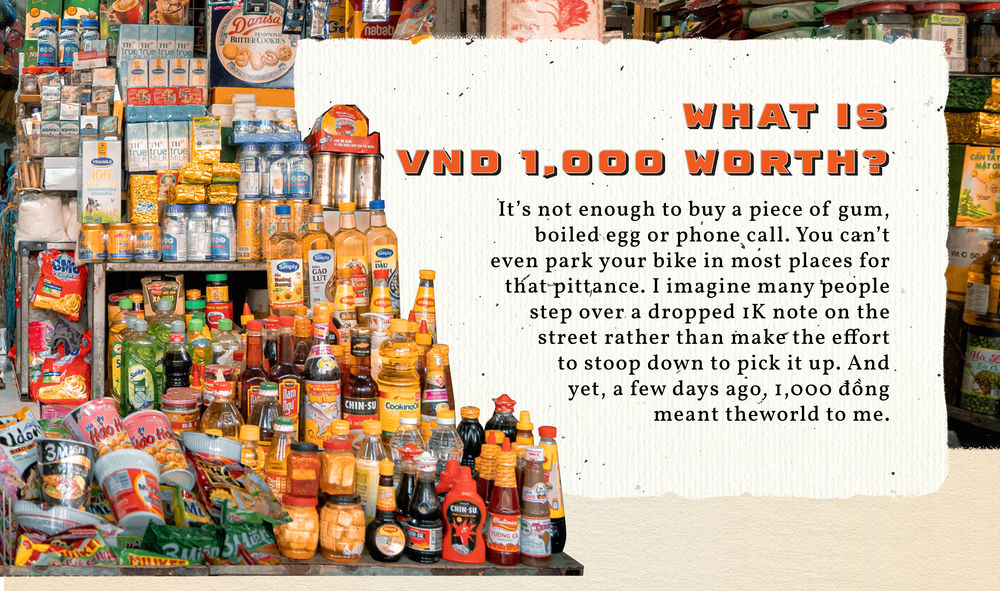

One day after work, I stopped at my local tạp hóa to pick up a bottle of rice wine, a bag of chips and a can of beer. The man who runs the shop, as he does with all customers, tallied up the purchase on his calculator and, despite it totaling VND51,000, asked me simply for năm mươi. It’s possible he didn’t want to fuss and fumble with making change, even though I had the exact amount already in hand, but I’d like to think that it was a small discount earned after years of weekly visits to his shop to buy everything from beer to batteries, pens to toilet paper. Though we exchange little more than pleasantries, the husband and wife who own the shop situated beneath their home have become familiar. If one considers tạp hóa important community institutions, that 1,000 felt like a subtle sign that I was further ingratiating myself in the neighborhood. As an outsider in Vietnam, this is no small matter.

A typical mom-and-pop shop in Vietnam

I’m not so mawkish to attach so much sentimentality to the scene that I saved the banknote. But I did pause to look at it a bit before placing it in my wallet. The depiction on the back of an elephant hauling lumber seems preposterously out of place in a time when massive trucks rumble down Saigon’s highways beset by an increasing number of private cars ferrying the nation’s emergent middle class. Living in Vietnam, perhaps more than in many places, one bears witness to constant reminders of the pace of societal change, the confluence of tradition and modernity and the intersection of familiarity and foreignness. One recognizes all of these elements in tạp hóas and their role in Vietnamese society.

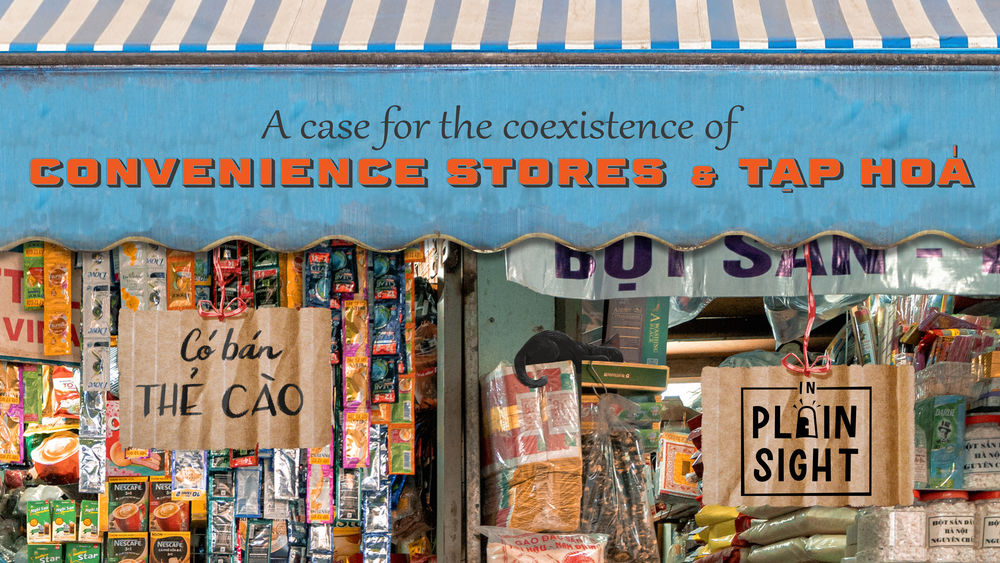

If you need it, the tạp hóa probably has it: deodorant, shaving cream, cream-filled crackers, powdered milk, plastic toys, packaged pastries, chili flakes, toothpicks, toothbrushes, toothpaste, pickled plums, popcorn, juice, napkins, nail clippers, cooking oil, canned sardines, ceramic bowls, candles, chopsticks, coconut milk, eggs, sacks of sugar, salt, baking powder, hand sanitizer, diapers, chewing gum, cashews, adhesive, shredded pork, peanuts, umbrellas, insect repellent.

Strings of shampoo and body wash packets hang on either side of many tạp hóa entryways like absurd aluminum moss or perhaps the beaded curtains that once concealed the seedy backrooms of Saigon’s GI bars. The single-use sundry items fill me with a certain sadness. Larger bottles are certainly much cheaper per ounce, but many people live in such economically precarious situations that such a purchase is unfeasible. Some days, I’m able to convince myself that no, the sachets are actually aimed at people so afflicted by wanderlust and a thirst for adventure that they can’t be certain they’ll use the same shower for more than a day. But neither reality nullifies the environmental impact of the packaging, and I detect great guilt and arrogance wafting off humanity; a stink that can’t be soaped and scrubbed away.

Thread, buttons, needles, scissors, strings, clippers, cords, and tape-measures. Once the circular Royal Dansk tins have been emptied of their mid-tier cookies, they become holders of household sewing materials. Your mom or grandma probably has one in her house right now and there is a good chance it was purchased as a gift from a tạp hóa. But what will happen to these metal containers when fewer and fewer people know how to stitch? We can’t let them go empty! I propose a few other uses: art supplies, makeup, jewelry, cash, contraband, blockchain wallet passwords, or perhaps even a loved one’s ashes.

One buys a small packet of salt at the tạp hóa without giving much thought to the common cooking product or its nearly negligible price. Yet, if you lived in Europe 500 years ago, you’d think about that purchase very differently. Thanks to the scarcity of spices, and the rigors of ocean trade, a single kilo of salt would cost more than US$2,000 in today’s currency. Sometimes I pick some up at the tạp hóa and sprinkle a little on my tongue to remind myself of the riches I enjoy in the modern age. I do the same with MSG, a glorious substance that was only invented in the 20th century, to celebrate the splendors of science, innovation and the evolution of the human experience made possible through collective knowledge.

What is the lifespan of a plastic poncho?

The type of plastic poncho hanging on a hook in front of a tạp hóa that you buy for VND10,000 when the cloudy sky shudders and you’re still three clicks from home and lack the patience to shelter beneath a bridge or building even — how long do those last? Do you get only one use out of them? Two? Three? And then what happens to them? I haven’t heard of anyone repurposing them. Certainly not to be used as replacements for a pillow cover. No, they get tossed into the trash and contribute to our dizzying plastic waste problem that chokes sea turtles and poisons porpoises. Is that worth staying moderately dry for? What’s wrong with a little rain — you’re not made out of sugar, you won’t melt.

There is no uniform system governing what a tạp hóa carries. The proprietors make the decisions based on personal preferences and prejudices, local customer needs, relationships with distributors, suppliers, and product availability. There are the standard items one will find at each, like bottled water, fish sauce and candy. And then there are the outliers and odd one-offs. Like boiled quail eggs, Japanese durian pastries, Vietnam Airlines napkins and tiny liquor bottles pilfered via a relative who works as a flight attendant.

If you owned a tạp hóa, what oddities would you stock?

If you owned a tạp hóa, what oddities would you stock? I think I’d have a “take a photograph, leave a photograph” box where people could drop a picture with no context or explanation. The snapshots would be simple ways to peek into a stranger’s life and have someone do so in return. They would function like encountering a single sentence of a novel you’ll never get to read the rest of.

An element of Saigon’s tạp hóa scene demanding discussion is the import stores on Ham Nghi Boulevard. These ramshackle assemblies of foreign foods have a dazzling array of sugar-bombed breakfast cereals, jars of gherkins, muffin mix, cake sprinkles, Pop-Tarts, taco seasoning, blended curry, Russian caviar, Kentucky bourbon, blocks of cheddar cheese, frozen bratwurst, blueberry jelly, canned peaches, snap peas, string beans, au jus sauce, dried lentils, linguini, matcha, mustard, chocolate bars, cornbread powder, and so on and so on and so on all crammed on shelves that reach to the ceiling. The buildings' cramped, narrow lanes force shoppers in search of exotic items to shimmy, jostle and shoulder-contort around one another with errant elbows, purses or backpacks sending a cascade of products tumbling to the floor. The city’s newer, more luxurious import grocery chains and malls free shoppers from this chaos, yet do so via significant price markups on each item. Is it worth it? And when buying a foreign product in Vietnam, doesn’t finding it in an exceedingly local store increase the exoticness of it? Aren’t humans drawn to the exotic?

A man hops the curb, and without getting off his motorbike or even turning the engine off, shouts chị ơi at the front of the tạp hóa. Inside, a woman rises from the floor where she and her family are having fried fish, pork omelet, stir-fried morning glory, and rice for lunch.

The living space tucked behind the storefront contains a child’s desk, ancestral altar, TV blaring some singing competition and a hammock swinging above a stack of newspapers. She sells the man his pack of cigarettes and returns to her meal. This common scene is a visual manifestation of the way tạp hóa conflates an owners’ family life, leisure time, labor and community. But how much longer will society work this way? As more and more people move to 9-5 jobs in offices or factories, one’s professional and private roles and relationships become more clearly delineated, like an atlas slowly filling in with borders during the age of exploration.

Walking in the middle of the night, the roads devoid of traffic, sidewalks free of pedestrians, restaurants darkened, the city’s emptiness can feel overwhelming; the buildings above start to resemble surreal cuspids in the maw of some beast eager to swallow you whole. The families that run tạp hóa have long since gone to bed and shuttered their storefronts with heavy metal gates and padlocks. And then, from the blackness emerges a bright white light — a soothing spill of warmth that is less a beacon than a soft voice calling to you: Here, over here, you’re not alone. The convenience store is always there for you.

7-Eleven, Mini-Stop, Circle K, Family Mart, Champs and even VinMart do a lot that tạp hóa don’t. Not only are they open 24-7, they also feature an array of hot food items and snacks while providing an essential space for people to congregate. Many feature expanded seating areas that fill up with uniform-clad students bent over homework, scrolling social media or simply chatting. "We used to study at coffee shops before we discovered the convenience store. It has air-conditioners, WiFi and cheaper drinks," explained student Tran Hoang, currently studying at the HCMC Medicine and Pharmacy University.

Around 78% of those occupying convenient store seating areas are teenagers or those in their 20s. It makes sense. Where else are they going to go? Parks are few and far between and become sketchy at night, bars and restaurants expensive, family homes sometimes oppressive and without privacy. Free internet, air conditioning, bathrooms, just enough jaunty pop music to keep conversations private and not overwhelm a person reading a book, it’s almost as if teenagers were designed in response to the existence of convenience stores, and not the other way around.

If the items at tạp hóa allow nostalgic reminders of items from childhood, the shelves at convenience stores reflect the new products arriving in Vietnam: Doritos, hanami Kit Kats, BBQ-flavored popcorn, Thai shrimp chips, craft beer, banana milk, iPhone cords, Exploding Kittens card games, facemasks, sexual lubricant, ice-cream bars shaped like fish, natto, string-cheese, frozen pizza, and a smoldering vat of mild broth with meatballs, sausage and eggs and upfront.

Perhaps the most emblematic item on offer is the ubiquitous triangle sandwich. Assembled in some unknown, distant warehouse, they come in a variety of flavors: egg salad, tuna, sauteed chicken, and “mixed.” They are easy, affordable, and packed with enough precisely balanced chemicals and preservatives to tickle the pleasure centers of one’s brain. Like drinking and smoking, one could forgive, even embrace, their unhealthiness if they were honest. They are anything but. Peeling the pieces of bread apart confirms the canard: while the ingredients are stuffed to the front to look robust in the packaging, the back half of each holds hardly any filling, just two dry pieces of bread touching with all the titillation of holding your grandma’s hand in church. The contrast between what it looks like you’re buying and what you actually get is an affront to one’s intelligence.

If not a restoration of hope and trust in the world, the convenience store sushi offers a better culinary experience. Delicious and lacking any deception whatsoever, it also allows you to feel like the apex predator you truly are. Imagine a 200-kilo tuna — the top of its food chain, zooming at 40 kilometers an hour — being ripped from the depths by little more than a string, a pole and a human hand. The fish then travels from a stretch of open Pacific to port to processing plant to packaging center to your palate. Your australopithecine ancestors could never imagine you reclining on a couch in some air conditioned hovel in Phú Mỹ Hưng snacking on such a monstrous sea creature. The convenience store affords you this pleasure.

It’s not just tạp hóa that convenience stores are competing with. In addition to the restaurants that their foods are fighting taste buds for, they are pulling business away from beauty shops and pharmacies via their selection of cosmetics. Thanks to influences from abroad and increased spending power, Vietnamese are buying more skincare products than ever before. Complex rituals involving creams, masks, moisturizers, scrubs and washes have replaced the arduous task of applying shining lacquer to one’s teeth. The literal black and white difference reveals that while fashion changes, one’s willingness to endure lengthy rituals for the sake one’s appearance remains.

Convenience stores can also be portals

At night, Thai Van Lung Street is quiet: as District 1 empties of its office workers for the day and the streets clear of the food carts that cater to them, the road becomes desolate, save a group of men drinking on the corner, a stray dog scavenging through trash piles, or someone entering a luxury hotel. Thai Van Lung’s Family Mart is similarly dead: the staff idles beneath the fluorescents before a lone businessman plops a bottle of tea and instant noodles on the counter. Yet, there is a back exit. Passing through it, one becomes immediately overwhelmed with the chaotic, almost synesthetic assault on the senses that is Little Tokyo: the cacophony of clinking glasses clattering out izakayas and echoing through the narrow alleyways; oily smoke wafting off sizzling pork slathered with teriyaki sauce alongside takoyaki, those moist tentacle-laden morsels; red and blue lights strung overhead blend in the humid light to give the entire scene the same purple hue seen on a bruised fruit that’s still fit to eat.

For all the joys they offer, a precise misery accompanies the modern convenience store

A misery in the beep of a scanning gun, of an ever-changing labor force consisting of young people earning a paltry VND30,000 or less per hour with profits going to overseas corporations, the bananas sold in plastic bags, eggs in plastic wrap, straws encased in plastic, the plastic sleeve that circles a plastic cup that contains artificially colored sugary drink poured from a giant vat behind the check-out that spins, spins, spins, spins, spins; staring at it while waiting in line can induce a certain meditative trance.

Your mind seems to leave your body, perhaps slipping into someone else’s, perhaps the staff member working the register, perhaps the character in the novel, Convenience Store Woman who proclaims: “When you work in a convenience store, people often look down on you for working there. I find this fascinating, and I like to look them in the face when they do this to me. And as I do so I always think: that's what a human is.”

Vietnam hasn’t sold its soul to the convenience stores quite yet, though. Tạp hóa and traditional wet markets represent 75% of fast-moving consumer good (FMCG) sales and a recent survey revealed that 92% of locals prefer buying basic necessities there. Respondents and experts cite a great variety of reasons for the preference, with convenience near the top of the list. After all, one seems to pass one at every turn when walking in any neighborhood — rural or urban — across the country. They also accept debt, meaning the local kid the owners have seen grow up can come in for candy his parents will pay for later, or a family down on their luck can have their canned milk put on layaway. And a person can purchase small portions of whatever they need. If you find yourself lacking a few pinches of sugar to finish making dinner, just pop next door and get the precise amount. No need to splash out for a large container that will linger in the cupboard.

But times may be changing. There are an estimated 1,200 convenience stores in the country and, despite having failed to meet previously set goals, experts expect significant growth in the coming decade. As the youths who grew up on convenience stores constitute a larger share of the economy, the market may shift to cater to their preferences.

The ability to use credit cards and pay electricity and water bills may lure them. Or maybe it will be the store’s expanded array of international products. Or maybe the soft, comforting light and hum or air conditioning that will elicit nostalgia for simpler, teenage days.

The future is perhaps best summed up by a scene that played out last week at a tạp hóa near my home. A shopper selected a typical assortment of products: cartons of yogurt, bar of soap, bag of peanuts, and placed them in a tote bag emblazoned with a Family Mart logo no doubt given as promotion for having achieved some spending threshold or point system. As with many aspects of modern society, the traditional will continue to co-exist with the modern. Women will have both an áo dài and a pants suit hanging in their closets; buses will fill with people wearing nón lá and baseball caps; there will be cải lương shows and hip-hop concerts; youths will wash down bowls of phở with bubble tea. Vietnam has always looked to simultaneously embrace the past while adapting to the future.

If a tạp hóa’s chaotic nature and variety of community purposes mean it can be likened to a symphony, then perhaps a convenience store is a cleaner, more straightforward concerto? Different moods demand we listen to different records.

Written by Paul Christiansen.

Graphics by Hannah Hoang and Uyen Ngo.

Production by Alberto Prieto.

Photos by Le Thai Hoang Nguyen and Alberto Prieto.

In Plain Sight is a Saigoneer series exploring overlooked or under-appreciated places in the city. We hope it inspires you to notice the many fascinating stories, histories, and ruminations waiting right in front of your eyes. Have a place that you cherish and want more people to notice it? Write to us via contribute@saigoneer.com.