By (un)conventional standards, Saigon’s Geological Museum may warrant a score of 1.3/9, but if one considers it as a source of whimsy, it’s a solid 8.2/9.

For years, Saigoneer’s editorial staff has discussed visiting and writing about the Geological Museum (Bảo tàng Địa chất), but it never got done. I’ve lived here for half a decade, and when I moved to a new neighborhood a year ago my daily walk to the office took me past the museum; yet I still had never entered. Then, on a whim, one random Tuesday morning several weeks ago, I went. The result? I didn’t think I could love Saigon more than I already did, and yet…

The Collection

When a meteor, a hulking hunk of prehistoric mass, shreds through Earth’s atmosphere and slams into the surface, the impact vaporizes terrestrial scraps of minerals and sends debris into the sky. The molten globs float like glassy raindrops and fall thousands of kilometers away. Buried under layers of rock laid over millions of years, occasionally the shiny shards work their way to the surface; shimmering examples of Earth’s immensity and the intensity of time. Have you ever seen one? If not, you can.

A case filled with these tektites awaits in District 1 alongside literal pieces of lava, impressions made by long-extinct sea creatures straight out of a science-fiction movie, and wood transformed to stone. Can you imagine, wood to stone! What was once a tiny seed and then a towering tube of pulp pumping sap to a canopy of soft leaves made into solid rock by the geological machinations of our exceedingly strange planet. No one seems to care.

If they did care, the Geological Museum might receive regular visitors. Instead, my arrival came as a shock to the gate attendee. Scrambling to turn on the lights and overhead fans of the museum’s single room, she passed me the log-in book. I was the second name on the list, and without a date at the top, I can’t be sure if I was the second guest of the day, the month or possibly the year.

I entered a single large room that consists of two dozen or so display cases arranged in two rows with a large table in the middle. A variety of rocks and minerals rest behind old filmy glass atop aged wooden cabinets; some of them ajar enough to notice they contain nothing but the types of odds and ends one might find in a neglected shed: batteries, newsprint, a microphone cord, random rocks.

The Trip Advisor reviews for the museum are brutal — "Unimaginatively organized. Unless you are very interested in Geology it is not worth the visit;" "Not amazing not exciting;" "We visited too [sic] check out the info of Ho chi min [sic], but this was very confusing and basic info" — but not entirely true. Visitors claim that there is no accompanying signage for the minerals on display, but each item does have a name beside it in Vietnamese, French and/or English (the linguistic hodgepodge is somewhat insignificant given the scientific obscurity of each term).

But while the curators of the museum do offer names, they don't feature information, in any language, about the specimens. Not their rarity. Not their origins. Not their uses. Not their age. Not their worth. The museum seems to be saying that if you don’t know why bauxite is so important, or can’t appreciate granite, or marvel at the delicate fossilized lobes of brain coral, that’s on you. As maybe it should be.

A Scant History

I left the museum somewhat dejected, somewhat bemused. Already my head filled with ways to ruminate on the value of museums in general, the failure of modern society to recognize our planet’s grandeur, and the intrigue of silt clay. I planned to pontificate on the failure of Saigon to support its museums, drawing on anecdotes of the Ho Chi Minh Campaign Museum needing to raise funds via leasing out its parking lot to weddings and the zoo’s continued efforts to replace animals with chintzy carnival rides and cafes. I was going to attempt heart-string-pulling comparisons to how I fell in love with the natural world and thus developed empathy at the Field Museum in America, where I grew up, and the paltry chance this museum would inspire the same in any Vietnamese youth.

But first, I thought maybe the building itself held a story. The Geological Museum occupies a single room of a run-down structure on Nguyen Binh Khiem Street adjacent to the zoo. The olive exterior wood is beset by a series of charming French shutters. They are all closed, and I suspect if the building were to have been repainted recently (certainly it had not), they would have been painted shut without anyone realizing.

I reached out to local architecture expert Mel Schenck, who told me that it’s an example of early Vietnamese modernism, but beyond that he has encountered nothing more regarding its construction or past. Local historian Tim Doling added that the museum moved into the building in 1973, but he doesn’t know what, if anything, it was used for before that.

The collection in its current form came into existence in 1954, when part of the collection of the French Service géologique de l’Indochine was relocated from Hanoi to Saigon and entrusted to the RVN Ministry of Economy. It was placed on view, initially, in a villa on Han Thuyen Street.

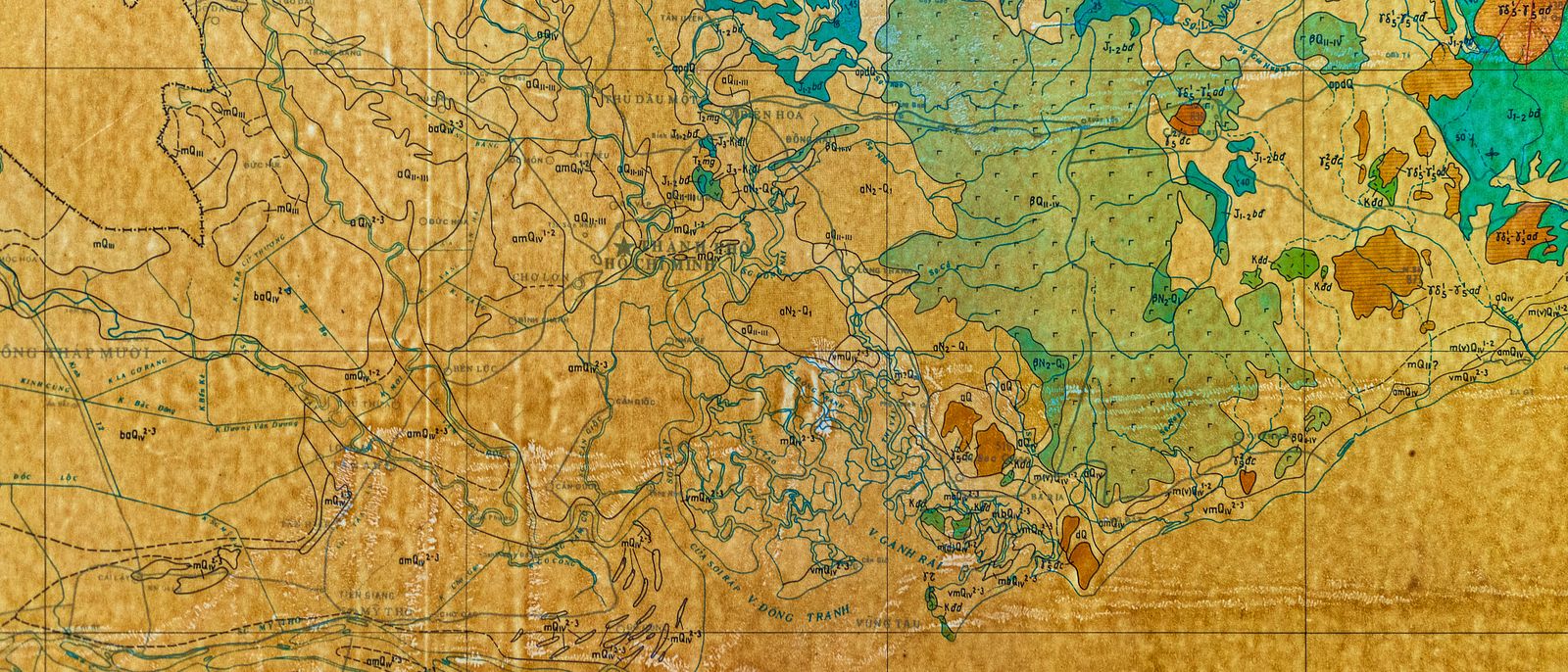

These bare details seem suited for the bare museum. The collection falls under the auspice of the General Department of Geology and Minerals of Vietnam, whose stated purposes include “doing researches, making geological maps; evaluating and exploring mineral deposits; collecting, evaluating and protecting natural resources, etc.” Established in 1945, its operations are crucial for the nation’s mineral and raw earth material industry as well as assisting with development and construction initiatives.

Public education about the planet’s fascinating history falls under their purview as well, but very little seems to be done in this regard. Saigoneer reached out to the department but received no response. Did our message fall into a spam folder? Was informing the public about the museum and its contents deemed too paltry to warrant a response? Or, perhaps the way one guards the location of a favorite coffee shop, the scientists want to hoard the knowledge for themselves, as if mainstream appreciation would sully it?

An Illuminating Second Visit

Shots of 1,500-year-old knives carved out of stone; dusty beakers filled with splintered minerals; some images of the horrendously out-of-date reproduction paintings that depict prehistoric fauna from Europe and the Americas in wildly inaccurate poses; perhaps a filmy photo that captured my disillusioned reflection on a display case paired with a caption regarding the inability of concepts of the self to supersede the permanence of granite — I had a shot list in mind for the second visit to the museum with Saigoneer’s photographer. They were mostly abandoned the moment the booming Vinahouse music hit us.

Several weeks ago, the metal gate of an adjacent storefront had been lifted, revealing a scurry of workers laying carpet and installing glass cases. Soon the telltale bouquets that accompany a store opening were placed out front. Then, a karaoke speaker. A sign proclaimed it as the “Exhibition Rock and Gem 2020 at the Geological Museum,” yet that seems as accurate as calling the city’s air pollution romantic Da Lat fog. And it wasn’t just one exhibition, as a second one occupied a space beside the museum's entrance on Nguyen Huu Canh.

After snapping a few photos of the museum’s first floor, the throbbing techno lured us like some synth-heavy Pied Piper. Small rubies, sapphires, garnets, amethysts and other stones rested on tiny trays in perfectly-polished glass display cases. Presumably sold for people looking to make jewelry, out of curiosity, we asked the man behind the counter for the prices.

“I don’t know,” he said.

I don’t know? The man’s most important job as shopkeeper is to know the prices for his wares and, if they are agreeable to customers, accept money in exchange for them. Without knowing the prices it’s a little unclear what his role was there. He didn’t seem to think his lack of knowledge was an issue, however, as he began pulling out semi-precious gems from his bag to show us. Rather than being frustrated (we weren’t there to buy gems, after all), his warm smile and affability quickly won us over. He spilled jewels on the counter for us to photograph, and even let us hold his gaudy gold and ruby ring all while bass throbbed into the mid-afternoon humidity. Certainly, this is the only museum with an atmosphere more appropriate for beer promotion girls offering watery larger samples than academics presenting research papers.

After deciding against purchasing the jewel-encrusted seashell display (as if we could have been told how much it cost anyway), we headed to the second exhibition room. Like the previous one, its display cases filled with jewels, watches, earrings and religious trinkets had business cards placed atop suggesting no specimens from the museum’s collection were pilfered to fill its shelves, but rather the space was rented out to jewel dealers on the simple assumption that visitors to the museum may be the exact clientele that would want to drop thousands of US dollars on stones.

Saigoneer may know a thing or two about modernist architecture, whale worship and iced tea, but our gem knowledge is scant. Thus, we were quite curious to learn exactly how much the stones are worth, none more so than the enormous rock on the ring worn by Thao, one of the store’s employees. US$30,000, was the answer. But it wasn’t hers, rather it's owned by the store, and wearing it is something of a uniform to meet the expectations of customers who ascribe value to hunks of inorganic matter that shimmers like laughter when the light hits them.

After marveling at the three images of Jesus Christ amongst the many Buddha pendants, learning a few things about sapphires (the lighter the color, the higher the value), and posing for the requisite photo with Thao, she asked if we’d visited the museum yet. Of course, we said we checked out the room. "The? No, there are five," she explained. Wait, what? Five?

Despite having been waived off by the lobby guard when I tried to go up to the staircase on my first visit, it seems that the building’s upper floors contain four more collections! After learning about this, we were again given the classic X-armed “no” by the guard. But when Thao emerged from the adjacent shop he had to relinquish. Setting down his cup of tea and the cellphone he was watching who-knows-what on, he sighed as he stood to guide us upstairs. He unlocked several sparingly-labeled rooms and in one case even had to remove a piece of tape that had been placed across the entrance.

In appearance and presentation, each of the additional rooms were similar to the ground floor: scant descriptions beneath nondescript rocks in shabby cases. Yet, a few whimsical items rested on the shelves. Mineral water. Simple, natural H2O with a smattering of dissolved salts, mineral water is as close to you as the nearest convenience store, and yet an entire display case was dedicated to bottles of it at the museum. Joined by precise chemical formulas, none of the three dozen or so samples were kept in sleek glass beakers, but rather seemingly whatever plastic bottle had been leftover from the previous night’s rice wine session.

Then there was the giant receptacle of Vietnamese crude oil. Oil, inarguably the most important compound of our modern age, is the enabler of a vast number of achievements, including rapid transportation and the electricity that fuels respirators and computer screens and the heating of homes. But oil is also a cause of the climate change threatening lives around the world, the source of the plastic trash choking sea turtles, and necessary fuel for wars that have slaughtered civilians by the millions. To see the unassuming black sluice resting so innocently in an old glass jug in the stuffy third-floor room reminds one that the simple compound holds no magic properties, and whatever brilliance or atrocity it is made to wreck upon the world is certainly a reflection of humanity.

As we stood gazing at the artifacts, snapping photos, the guard who had seemed so put off to labor up the stairs to let us in softened. He stood in the doorway taking our photo. Was he amused a crew of foreigners had taken interest in the museum? Was he an unabashed geology nerd who found delight in the idea that someone shared his passion? Is the Saigoneer dispatch so disarmingly attractive as to necessitate preserving in photo form? Unclear. But there was something profound in his action. What had been a stereotypical moment of a lazy staff member shirking his responsibility became one of wordless, acknowledged appreciation. He appreciated our presence in the museum and we appreciated his opening it up to us. What, if not appreciation, is the fabric that keeps our society together?

A Five-Star Review

Again, the Geological Museum is not a categorically good museum. The amount of information is poor and the collection of limited scientific value compared to institutions holding more rare and important specimens; the un-air conditioned rooms are hot and uncomfortable, and the staff is potentially so disinterested they might withhold 80% of the collection from visitors. Yet, it’s a glorious example of the splendors of Saigon. From horrible techno music to comically ill-prepared staff to commercial needs taking priority over intellectual pursuits, it's not perfect. And yet, the whimsy of water bottles tucked into display cases, the inexplicable and wildly inaccurate dinosaur mural in the motorbike parking area and, most importantly, the kind, colorful and generous people seem to exemplify the city.

You should go to the Geological Museum if you are a mineral nerd. You should go if you appreciate the soothing sound of footsteps on Vietnamese modernist stairwells. You should go if you have guests in town who are tired of typical cafes and nightclubs. You should go because, for all its flaws, the museum is unflinchingly earnest, welcoming (with a bit of luck), kind, a little strange and filled with unspecified history. It is Saigon. It is beautiful.

In Plain Sight is a Saigoneer series exploring overlooked or under-appreciated places in the city. We hope it inspires you to notice the many fascinating stories, histories, and ruminations waiting right in front of your eyes. Have a place that you cherish and want more people to notice it? Write to us via contribute@saigoneer.com.