France’s Vietnamese population is one of the largest outside Vietnam. From colonial assignments to refugee migrations, the community has grown, shifted, and evolved since its beginnings in the 1860s. Meet the new generation of French-Vietnamese creatives — chefs, authors, cultural consultants — who are reimagining and representing Vietnamese culture in Paris in fresh and deeply personal ways.

History of Vietnamese migration to France

Paris hosts the oldest Vietnamese community in the western world. Today, an estimated 70,000 people of Vietnamese heritage live within the city limits, and another 100,000 in the surrounding Île-de-France region — together forming one of the largest Vietnamese populations outside Vietnam.

The first arrivals were not immigrants in the modern sense, but Nguyễn dynasty diplomats and officials, sent in the late 18th century when France and Vietnam established formal ties. After France colonized southern Vietnam in 1862, Paris became a gathering place for Vietnamese civil servants, scholars, intellectuals, and artists — many of whom left an early cultural imprint on the city.

Door-to-door assortment of Vietnamese eateries and businesses in Paris.

When Vietnam gained independence in 1954, France remained an important destination for those seeking education or new economic prospects. But with the country divided and North Vietnam closed off, most newcomers during this period came from the South.

The upheaval of the American War brought a new chapter. The first wave of refugees, arriving in the months just before April 30, 1975, were largely political figures from the former South Vietnamese government and their families, beginning a larger and more complex migration story that would continue into the late 20th century.

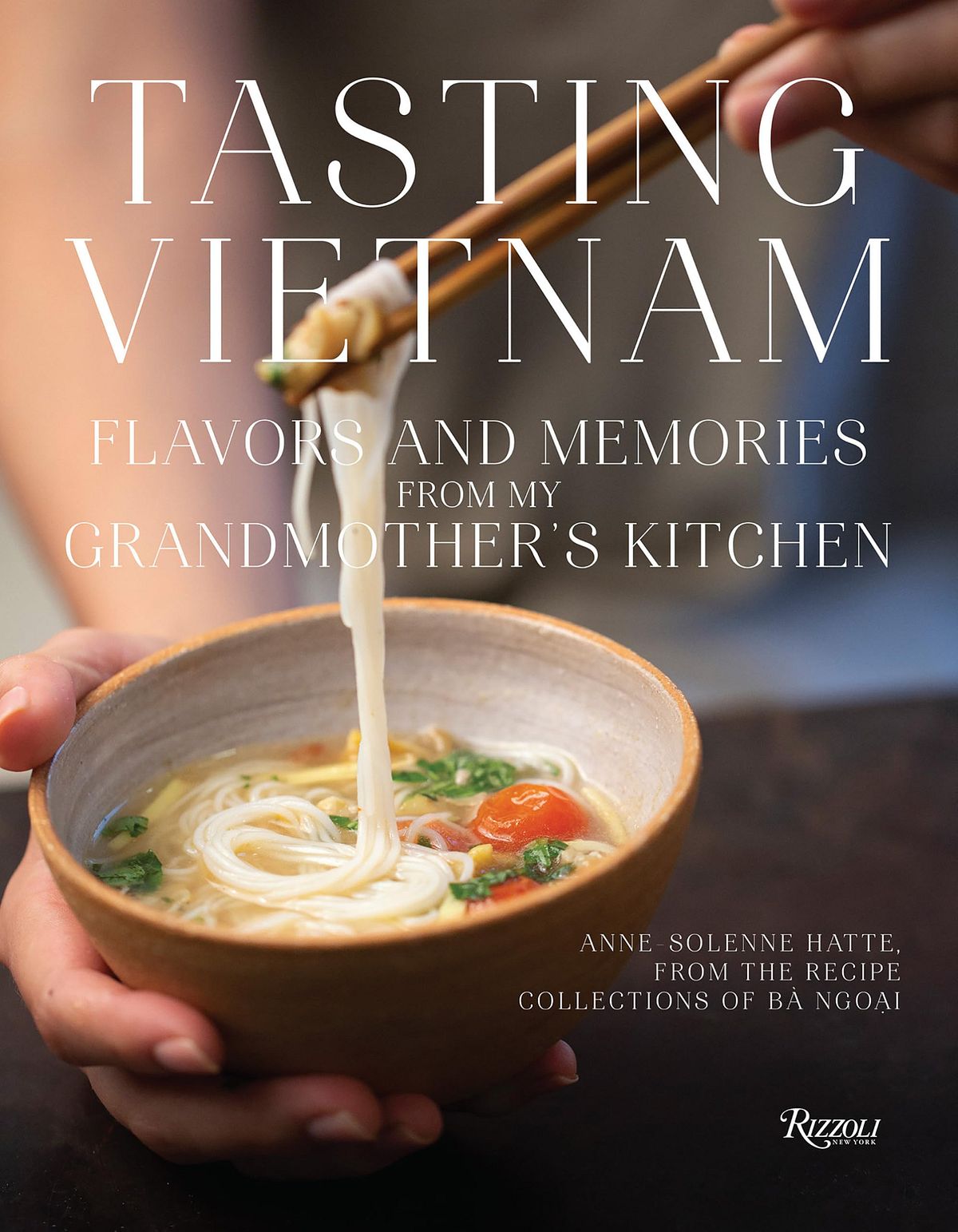

Anne-Solenne Hatte, author of Tasting Vietnam: Flavors and Memories from My Grandmother's Kitchen, shares with me that her grandfather worked in the previous government. “Even though he was a man of power, the one who was leading the family was really my grandmother... After [Diệm’s assassination], my grandfather had a job offer in Taiwan for a political position, but my grandmother said, ‘No more politics. It's done. We have nine children, and we need to take care of them.’” Because of her grandparents’ involvement in the Catholic community, a cardinal helped them immigrate to a small town in the center of France.

The cover of Anne-Solenne Hatte's book. Image via Amazon.

Vietnamese refugees, like Anne-Solenne’s grandparents, had to do what they had to do to stay alive, which often meant opening restaurants. She recounts: “My grandmother couldn't look back to her past. She needed to survive and move forward by creating a Vietnamese restaurant in the garage of their government-subsidized house without any money. It was not a project of the heart, it was a project of survival. They needed money.” She goes on to describe a small space, a third of the size of the hotel bar we were sitting in, that could only fit four dining tables. “All of the children participated. My mother and all of my aunts and uncles had a special skill: you do the appetizer, you do the main course. My mother and her twin were the waitresses. My grandmother would wake up at 6am to start cooking and work until 3am.”

Anne-Solenne Hatte (left) gathers her bà ngoại's (right) most loved recipes into a book project. Photo courtesy of Anne-Solenne Hatte.

The family recipes have always interested the former actress: “My grandmother is very close to me, even though she passed away five years ago — she's still with me every day. So the cookbook is very important to me. When I first started, it was just a cookbook for my family because there are 60 of us. Every one of us loves cooking, and I felt it was easier to have something like a dictionary where we could put all our recipes together.”

But as anyone who has ever asked a Vietnamese person for a cooking lesson knows, collecting recipes is a lot more challenging and less straightforward than it sounds. “By the time I stayed with my grandmother, I realized her recipes were alive,” Anne-Solenne recalls. “Because she had moved between Vietnam, Washington, D.C., and France, she needed to adapt and recapture the taste without money, without nước mắm, without crabs, without whatever ingredients.” The completion of her book Tasting Vietnam, which weaves recipes with memoir, is made even more impressive considering their language barrier. In her words: “I don’t speak Vietnamese, but I speak the language of taste, the taste of Vietnam.”

With a cookbook under her belt, Anne-Solenne just wrapped up production on a documentary featuring videos she recorded of her grandmother in the kitchen and an open door to the past via found archival footage of her family. “I think food is a great door to storytelling [about the Vietnamese experience] because it brings joy and lightness. It’s more powerful than when it’s always linked with pain.” Her documentary is called Taste of Exile.

The tricky situation Vietnamese food got itself into

In the years following the American War, the 13th arrondissement of Paris, referred to by most as Chinatown, transformed into “Quận Mười Ba” by the 1980s, as waves of Vietnamese refugees had reshaped the neighborhood, filling its streets with the shops, markets, and gathering places that anchored the community in a new country.

A view of the Asian quarter in the 13th arrondissement of Paris in 1994. Photo by Pierre Michaud via Radio France.

While an Asian presence already existed in the area, the post-war influx turned it into a vibrant hub of Vietnamese life. Supermarkets like Tang Frères, Buddhist temples, travel agencies, bookshops, and steaming bowls of phở became fixtures of the local landscape. For many of the new arrivals, the restaurants weren’t just places to eat: kitchens became a source of community, serving familiar flavors to fellow refugees at prices they could manage.

“The first generation created restaurants to feed their own community. They sold their food for low prices so their fellow refugees could afford it,” Nam Nguyen, the proprietor of Hanoi Corner, a Vietnamese coffee distributor, observed. He goes on to explain: “Because of this, in France, Vietnamese food is expected to be cheaper than McDonald’s.”

As Julien Dô Lê Phạm, founder of the creative food agency Phamily First, argues in his Subway Takes video: “Southeast Asian food should get more respect, or at least be treated equally as any other cuisine. I love Italian food. I love a good cacio e pepe. It’s the most common dish that can be done in 5 minutes. You know phở? You have broth that was made the day before, with bones, with a lot of love, with the spices and everything. You have meat in three different forms. You have fresh herbs. You have everything. Phở is around EUR12–15... But people are willing to pay US$30 for the cacio e pepe.”

In addition to being cheap, Vietnamese restaurants in France have traditionally been seen as indistinguishable from one another and pigeonholed into making only a few well-known dishes. From a dining table across the street from Pont Neuf, the team behind the food and beverage brand Hà Nội 1988 explained to me: “Older generations go to the 13th arrondissement for Vietnamese food, but rarely with a specific restaurant in mind.” Among the French, bò bún is the most popular dish, surpassing even phở. Bò bún is so popular in France that even Thai or Chinese restaurants serve it. In my opinion, when chefs outside the culture start serving a dish, it’s a surefire sign that it has become both popular — and profitable.

As a concept, bò bún is fairly typical Vietnamese fare, but the name might be unfamiliar to Vietnamese outside of Europe, who would call this dish bún bò xào. Photo via Grazia.

As someone who has only heard of bún bò, and never bò bún, I was a bit confused. Bò bún is a bowl of rice vermicelli noodles topped with stir-fried lemongrass beef, lettuce, cucumber, mint, cilantro, bean sprouts, pickled carrots, roasted peanuts, and a fried eggroll — which is called “nem” in French, after the northern term, instead of the southern “chả giò.” Bò bún is served with nước chấm. In Vietnam, we would call this dish bún bò Nam Bộ, bún bò xào, or bún thịt bò xào. Why the name was flipped in France remains unknown, but it's a mystery many of us would like to understand.

Expanding France’s understanding of Vietnamese food

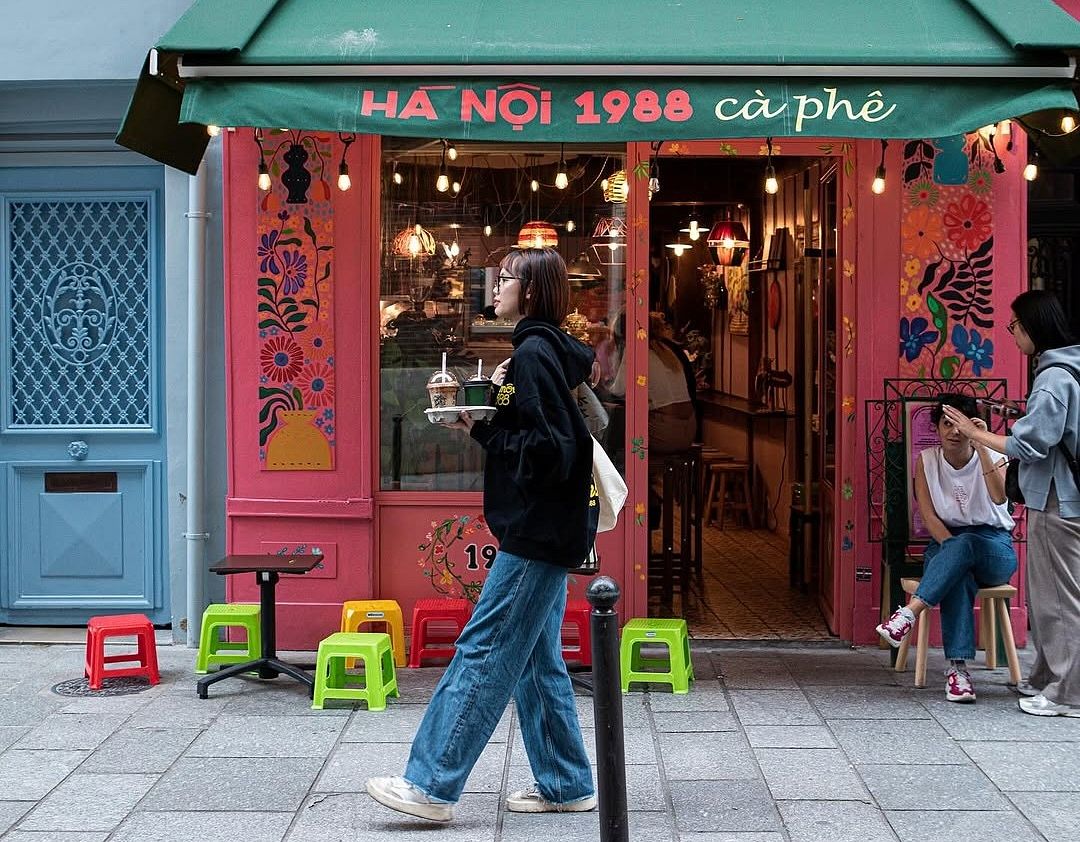

Steps from Notre-Dame, Hà Nội 1988 feels like a time capsule of Vietnam, with its retro décor and menu of familiar, soulful dishes, rooted in the flavors of the north. Founded in 2020 by Huy Nguyễn, a former photojournalist from Hà Nội, his dedication to developing his own northern-style phở earned him the Golden Anise Award from the Vietnamese Culinary Culture Association and Tuổi Trẻ. From there, Hà Nội 1988 has become a pioneer in introducing northern Vietnamese cuisine — beyond the usual phở and nem — to French audiences.

When I asked Uyên Trần, the general manager, and Phương Trần (no relation), the marketing lead at Hà Nội 1988, about the popularity of northern Vietnamese cuisine in Paris, they laughed and said, “Now restaurants are serving northern dishes. We can’t say if it’s because of us, but we know they were far less common before Hà Nội 1988 opened.”

The Hanoi 1988 team and their location. Photos by Tâm Lê.

They also emphasized the importance of their central location, outside the expected 13th arrondissement, in expanding non-Vietnamese’s understanding of Vietnamese food. “We have many Parisians dining here, and a large number of international visitors from China, Korea, and the United States, particularly Asian Americans. Several social media food influencers and prestigious chefs, including Chef Hélène Darroze [a long-time juror on French Top Chef], have taken notice of us, which has helped draw in an even more diverse audience. For us, it’s a source of pride to bring Vietnamese food closer to people from all over the world.”

But it’s become about so much more than food. Both Uyên and Phương came to Paris, from Vietnam, for college and started working at the restaurant as a part-time job. Uyên recounts, “Before I started working here, I didn’t realize how important it was to share Vietnamese cuisine and culture. At first, it was just a part-time job while studying in France, but over time I became proud of what our food represents. And I believe many members of our team feel the same.” She smiles as she continues: “Now it’s not only Vietnamese people who are opening Vietnamese restaurants and coffee shops, the French are doing it as well. Vietnam has become kinda trendy in Paris.”

Outside the Hanoi 1988 Cafe in the Latin Quarter. Photo via Time Out.

And in the five years since they’ve started, some of those were during the COVID-19 pandemic, Hà Nội 1988 has certainly started moving from cuisine into culture. They’ve got two restaurants and two cafés, the latest one being Hà Nội 1988 Flowers and Archives in trendy Le Marais, which offers not only coffee, but workshops on flower arrangement, paper flower making, and other skills. They’ve got their own merch and have collaborated on pop-ups with companies like Uniqlo. They’ve recently released a cookbook, and possibly, one of the most exciting pieces of news: they brought Hanoian coffeehouse Cộng Cà Phê to France.

Cộng Cà Phê's first location in France. Photo via Cộng Cà Phê.

I arrived in the 2nd arrondissement, steps from the Paris Opéra, just before the official grand opening of Cộng Cà Phê’s first French outpost, to see a space that looked more like a war zone than a café. Tarps hung like makeshift barricades, hammers echoed against exposed walls, and the scent of sawdust lingered in the air. In the middle of this chaos sat Giang Dang, the café chain’s CEO, coolly stationed at a laptop in the back corner. She didn’t need to raise her voice; her quiet focus carried the weight of command, like a field general plotting strategy while the battle raged around her. Even in the not-yet-completed café, the staging felt unmistakably Cộng: equal parts grit, vision, and discipline.

This Paris location on 18 rue Volney marks the brand’s first foray into Europe, an ambitious step for a café chain already beloved across Vietnam. For Giang, the significance of this moment goes beyond business. “We usually have brands coming to Vietnam,” she told me. “Now we can have a Vietnamese brand come to other places.”

For Giang, the decision was not only about expansion, but about who she trusted to bring the Cộng identity abroad. “We had inquiries before, from France,” she explained. “But actually, Huy [founder of Hà Nội 1988] was the first Vietnamese person to reach out. We did some research and saw his restaurants. That gave us the confidence that he could really do it. And I have to say, he has a very professional team.”

And this location won’t be the only stage. Giang shared that other new Parisian locations are already in the works, and the chain has its sights set on an even wider horizon. “My dream is to one day expand to New York, or Japan,” she said, her voice steady but the ambition clear. If Paris is the foothold, Europe — and beyond — may soon follow.

The future of Vietnamese food in Paris

The City of Light’s Vietnamese culinary scene is evolving from enclaved phở joints to high-concept eateries and hybrid café-boutiques. It reflects a generational shift: from first-generation immigrants who opened restaurants out of necessity in the 13th arrondissement, to second-generation and recent Vietnamese entrepreneurs" who now use food, design, and storytelling to assert identity in Paris’s most fashionable quarters. Many of these cultural ambassadors are eager to reclaim and redefine what “Vietnamese” means in France today.

Left: My Ly, the founder of Bà Nội (left); and Nam Nguyễn (right), the founder of Hanoi Corner. Photo by Tâm Lê.

Right: Bà Nội's gỏi cuốn. Photo via Bà Nội.

“My parents really didn’t want me to go into the restaurant business,” recalled My Ly Phạm, founder of Bà Nội. “When I told them my idea, they made me meet with a family friend who had a restaurant, just so I could see how hard it was. For that generation, it was about survival. But for ours, it’s different — we choose to do this work, we’re not forced into it.”

For My Ly, that choice meant building a restaurant featuring summer rolls. “At home, everyone rolled their own at the table: my family, my French friends, anyone who came over. It felt normal to me, but my French friends would always say, ‘Oh my God, this is so good.’ That’s when I realized I wanted French people to discover this way of eating.”

She pursued the idea methodically, studying business, working in restaurants during a gap year, and spending semesters abroad in Bangkok and later traveling through Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, and Hong Kong. Each place added something to her vision. “In Myanmar, by the lake, I tried fish with this peanut sauce that was amazing. I asked the chef what was in it, and that recipe became my sauce.” Her menu today blends memory and inspiration: tom yum adjusted to her own taste, teriyaki salmon, and that peanut sauce. “If I were opening now, maybe I’d ask if it’s legitimate to do it this way. But eight years ago, it wasn’t about legitimacy. It was about inspiration, about sharing flavors with French people in my own way.”

That balance between authenticity and adaptation is a recurring theme among Paris’s Vietnamese restaurateurs. Nam of Hanoi Corner, put it bluntly: “People in Vietnam don’t fight over their authenticity. Recipes vary and everyone just says, ‘It’s the way I like it.’ French food borrows from everywhere — Japanese minimalism, Chinese small dim sum plates, African spices — and that’s how it thrives. Like how the French kebab is different from the original, I want Vietnamese cuisine in Paris to grow the same way, to have its own French-Vietnamese identity.”

Julien Dô Lê Phạm with cơm hến and bánh mì xíu mại from Chop Chop's collaboration with Saigon Kiss. Photos by Tâm Lê.

“I feel like French-Vietnamese food is not born yet,” echoes Julien Dô Lê Phạm. We are sitting in front of his spot Chop Chop, a painfully cool wine bar that hosts a rotating cast of multicultural chefs. This week is the Vietnamese-Dutch collective Saigon Kiss serving central dishes like cơm hến and bánh mì xíu mại. People mill around us hoping for a seat to open up, as he continues: “I see what’s going on in New York and it’s so interesting. Ha’s Đặc Biệt is doing American-Vietnamese. Mắm is authentically Vietnamese. Bánh by Lauren is amazing. She’s doing something very authentic in a New York way. I feel like we are late in Paris, in terms of having the younger generation create restaurants with their own identity. There is a freedom in the US, where a mix of cultures in cooking is possible. Whereas in France, you are always seen as an immigrant — you need to do your food and adapt it to French people.”

Julien pauses as he chooses his next words carefully, “This event might be the edgiest Vietnamese thing in Paris right now, but the best is yet to come once us kids of immigrants are totally free to express ourselves. Creating something that is intentionally mixed was not possible until now. For a long time, it was only about French food, French food, no deviations, and Vietnamese restaurants were considered hole-in-the-walls. It’s only been recently that Paris has embraced its diversity and the kids of immigrants. That’s why Paris is so exciting nowadays.”

Julien’s optimistic sentiment reminds me of something Nam expressed earlier, laughing as we stood outside Cộng Cà Phê during their soft launch: “Being Vietnamese in Paris is finally starting to feel fun.” Santé to that!