"The artist can’t reflect the truths of life if they don’t live, can they?"

Táo, whose real name is Võ Hồ Thanh Vi, belongs to Vietnam’s earliest generation of rappers, having been making music since 2010. As a young rapper, Táo already had a number of impressive releases under his belt, like ‘Morphine,’ ‘Tâm Thần Phân Liệt,’ and ‘2 5.’ In 2019, he unveiled the debut album “Đĩa Than” after three years of production, in collaboration with six producers, including Astronormous and Teddy Chilla.

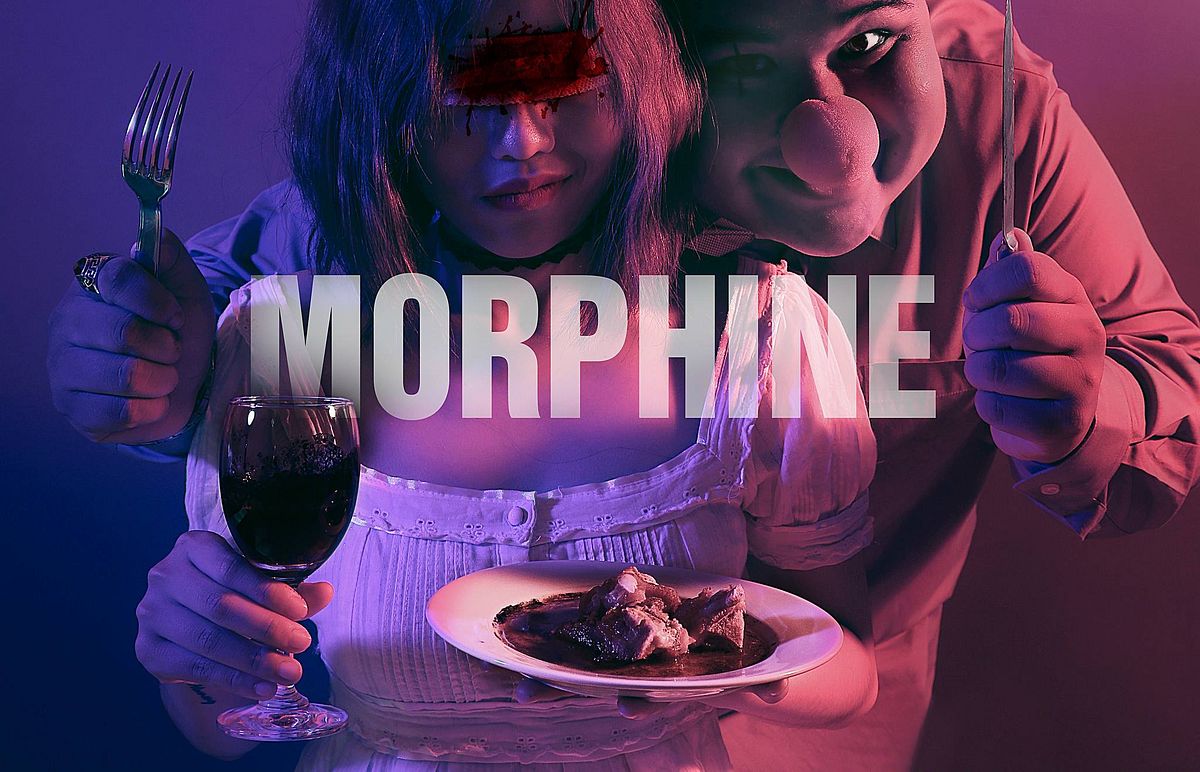

In Vietnam’s rap landscape, Táo’s music is characterized by an assured and distinctive flow that’s easily distinguishable. His early success like ‘Tâm Thần Phân Liệt’ and ‘Morphine’ has strong horrorcore themes — a subgenre known for its lugubrious ambiance and its focus on dissecting the dark corners of the human condition.

Oftentimes once a musician has managed to generate a hit song, they have to find a way to live in the shadow of that celebrated work. Táo is no exception. For the first 10 years of his journey in hip-hop, people almost always associated him with the anguish and antagonism of ‘Tâm Thần Phân Liệt,’ or the agony in ‘Morphine.’ Táo’s body of work is frequently labeled “sad, macabre, ghastly music” and he’s pigeonholed as the “artist for sadness.”

Táo experimented with horrorcore as a small project with a darker theme, establishing doom and gloom as the overarching atmosphere, but he’s never sought to broadcast negative messages or promote whatever the songs convey. He’s also never wanted to tie himself to any genre or topic, as he believes that will drain any last drop of creativity.

This vision propelled Táo to branch out more. “Đĩa Than” was born of a pessimism within someone going through mental health problems, drenched in woe in between the jazz and hip-hop notes. The album also marked the end of the decade for Táo under the label of a rapper. A year later, he introduced ‘Blue Tequila,’ the lead single of the EP “Y?” and reincarnated under a new direction of just as Táo, someone who makes music.

From Morphine to Blue Tequila.

The adventure to find a new character in music led Táo down a path toward different art practices like painting, photography, cooking, etc. He tried things out to hone observation skills and to experience the special personalities of each art form. He chose to not widely share his work and only keeps them for his close friends and family who really know who he is.

It’s easy to notice the growth Táo has achieved, as demonstrated in every single he’s put out for the EP. ‘Blue Tequila,’ the appetizer, establishes a scene, using inspiration from the common liquor. ‘Tương Tư,’ the next course, plays on ideas from fashion; the costume that carries the key visual was custom-made. And lastly, ‘Red Rum’ is a feast with a cocktail, perfume, fashion, saxophone, and even a brush with contemporary dance. Above all else, each song comes with a poem and artwork from contemporary artists and poets.

Even though there is a confluence of many elements in this record, Táo views every piece as an expression of his life, not just as marketing gimmicks: “If I practice art just for the sake of it, I can’t immerse myself in life. I just want to stand on the side to observe the beauty of life. The artist can’t reflect the truths of life if they don’t live, can they?”

From left to right: scenes from the music videos for 'Tương Tư,' 'Blue Tequila' and 'Red Rum.'

Some artists decide to expand their artistic repertoire just to become too distracted in their own path; they dabble in many areas but can’t master any. Táo is very keenly aware of this pitfall, and wishes to keep himself as just “someone who makes music” instead of “artist.” He often reminds himself that his stints with photography, perfumery or painting are just detours to enrich his journey with music.

The interdisciplinary nature of the extended play means that the final result is not just due to Táo’s efforts alone. Its concept was shaped like a small seed that receives love and care from many other arts from different art forms. They are the painters, directors, dancers, designers, perfumers and musicians who took Táo’s ideas and transposed them into their own pieces.

Those experiences with other art forms helped form a connection between Táo and other artists. He approached with an interest in the basics and the experts came with the rest.

“By trying new things, I realized that by myself I can’t do things the way someone with the skills can. It helped me put down my ego to delegate components to the artists, and focus on perfecting my part in music. It’s how I learn to trust people with my work, because before, my music creation process happened solitarily in my room,” Táo shares.

When a music release encompasses many different features from other fields, it allows for a richer experience for the audience, who can approach the work from many angles. With ‘Red Rum,’ one can get through to the music via its uniquely created cocktail, the dynamism of alto saxophone, the fragrant notes of the perfume, or the elegant movements of the dancers. "I hope we can get past the belief that within a project there must be a central component and peripheral add-ons. Sometimes, everything you see in front of you are all shining parts deserving of appreciation."

After the full release of “Y?”, Táo embarked on yet another new quest in his art practice with an exhibition showcasing the pieces created within the realm of the extended play. He wanted to offer listeners a way to tangibly experience the work outside the limitations of sounds. The exhibition was held in early December last year.

When asked about the intersection of forms in art, Táo explains that it’s an inevitable outcome. The arts are closely interwoven with culture and they will grow when culture grows. Many experiences that we are currently enjoying came from the adaptation of foreign art practices; if there is no cross-culture learning and experience, culture might become stagnant.

Even though Táo’s belief is steadfast, he admits to feeling daunted by pressures, both from himself and from the audience. “But I still believe that new things take time to get used to. The prevalence of the internet provides a chance for Vietnamese music to rub shoulders with new forms of expression. Maybe somebody in Vietnam has already done this or that thing, but they are still trying to find their own community. Just you wait.”