When I first started as a writer, I noticed that I couldn’t write in Vietnamese very well, despite the fact that I was born here. Most of my English vocabulary comes from books, so in order to improve my mother tongue, I began reading Vietnamese texts. The first one I chose was Hà Nội Băm Sáu Phố Phường, or The 36 Streets of Hanoi, by Thạch Lam. This book had been lying on my bookshelf for a long time, but that day was the first time I picked it up.

Before reading any sentence of Thạch Lam, the foreword written by Khái Hưng already made me cry — partly because of his excellent prose, which was concise yet profound. And I was touched also because they, whom I saw as writing colleagues, had laid out a literary path that I could follow for the rest of my life.

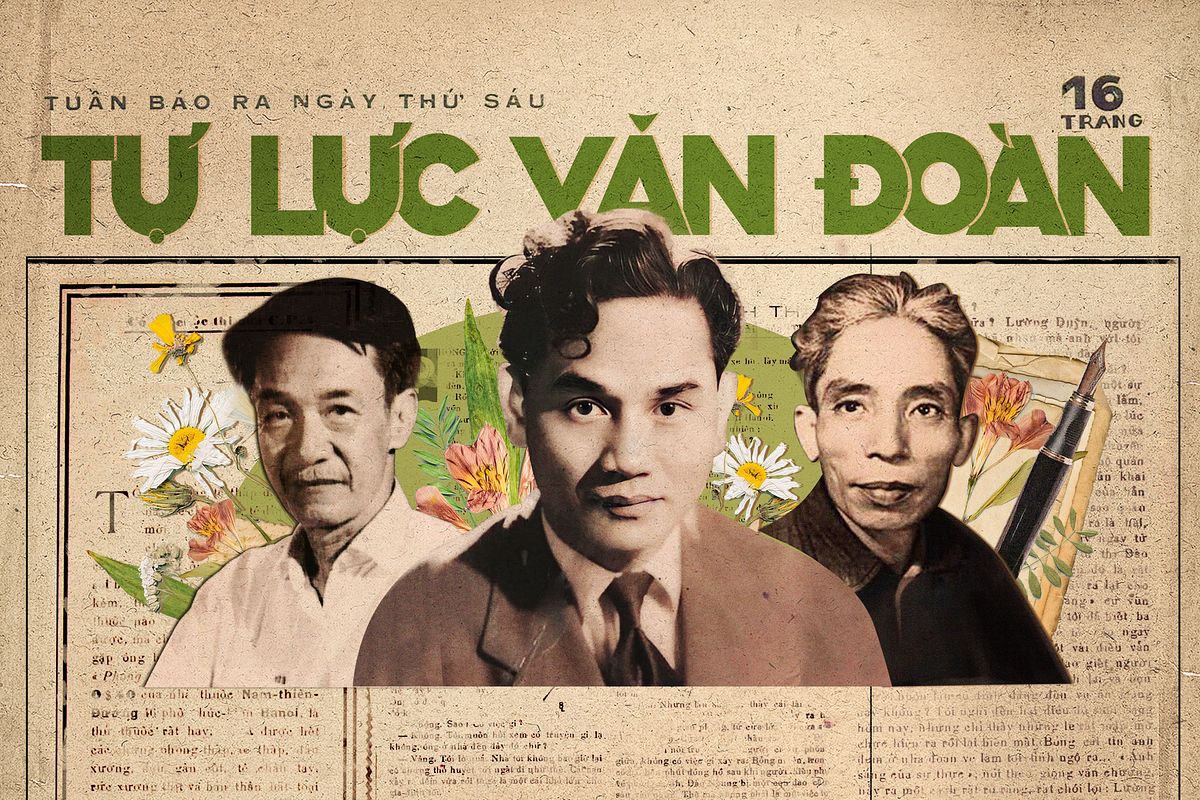

The logo of the Tự Lực Văn Đoàn collective.

A band of literary brothers

Thạch Lam and Khái Hưng were members of Tự Lực Văn Đoàn, or the Self-Reliant Literary Group. The writer collective was founded during the French colonial era with the purpose of "enriching our country's literary wealth.” As a reader loving their works, I was drawn to the story of Tự Lực. This was not just a story about writing and journalism, it was also about the destiny of a country — a story with tragedies that still resonate to this day.

Tự Lực Văn Đoàn's key members.

“The story of Tự Lực Văn Đoàn was a huge conflict of the Vietnamese society,” Nguyễn Đình Huynh tells me. Huynh has studied the Self-Reliant group for over 50 years; he was enraptured with their story because he was born in Cẩm Giàng, the same hometown as three group members — three siblings — Thạch Lam, Hoàng Đạo, and Nhất Linh.

“Around 1925, Vietnamese literature began to shift from the brush to the fountain pen," he explains. “At that time, all French government documents changed from Confucian script [chữ Nho] to Vietnamese script, so the literary world also moved from Chinese to quốc ngữ [modern Vietnamese]."

The newspaper's "Vui Cười" (Humor) section.

Although quốc ngữ has existed since the 17th century, it was not until the time of Tự Lực that people used it to create literature. “Besides Tự Lực, there were other people writing with quốc ngữ, but they were doing it separately and lacked association. The Group, on the other hand, was the collection of seven people, the seven best writers of all literary genres. Nhất Linh assigned their roles, this one writing essays, that one poetry… Thus, when they published a newspaper, they could cover it all.”

The Group’s work first reached its audience through Phong Hoá — Vietnam’s first satirical newspaper. With an issue in hand, readers could pore over a chapter of Nhất Linh's novel, then move on to Hoàng Đạo's social commentary, stay curious through Thạch Lam's nightlife reportage, laugh along with Tú Mỡ's satirical poetry, criticize the ludicrous mistakes of other newspapers along with Khái Hưng, shiver at Thế Lữ's horror stories, and recite Xuân Diệu's romantic poems. And holding true to the satirical identity, the section “Vui Cười" (Humor) had the most writers, with submissions not only from the whole editorial team, but also the public.

“The Self-reliant Literary Group gained popularity in the 1930s,” said Martina Thục Nhi Nguyễn, an associate professor of history at Baruch College at City University of New York. “They were the first generation who studied completely under the new Franco-Vietnamese education system. Compared to the previous generations of intellectuals, they were completely different. The previous generation of Phạm Quỳnh or Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh, if they wanted to be in academia, they had to study Confucianism. But then the next generation, of Nhất Linh, Thạch Lam, Vũ Trọng Phụng…they all learned western studies.”

In the curriculum of the west, they read foreign literature. Martina continued: “The contribution of the Group to Vietnam’s literature was applying foreign genres to create works in quốc ngữ.” The first principle of the Group was:

Instead of translating Les Miserables like Phạm Quỳnh did, the Group read foreign books, then reflected among themselves and created their own works, for their fellow countrymen, in Vietnamese. Take Thế Lữ, for example: he wrote a series of short stories about Lê Phong, a reporter who specializes in solving mysterious cases with Sherlock Holmes’ deductive reasoning.

When it first started, the Group hired a printing house to publish their books and newspapers. After that, they bought printing machines to open Đời Nay, their own publishing house. To see how popular the Group's books were, one can just look at the numbers. In the years from 1925–1945, the average book had 1,000–2,000 copies printed. As for the Group's books, at least 5,000 copies of each title were printed, with some reaching 16,000. Khái Hưng was the best-selling author with a total volume of 87,000 copies.

And then there were none

A portrait of Thạch Lam. Image via Hà Nội Mới.

In 1942, the Group lost its first member, Thạch Lam, to tuberculosis. In his final moment, his brothers in the Group couldn’t be there. Hoàng Đạo and Khái Hưng were imprisoned in Hòa Bình, while Nhất Linh had to flee to China; they had been involved in anti-French activities.

Huynh says: “If the Group had not failed in the revolution, then they would have been praised greatly. But they got into trouble because they were anti-communist. Some people say Tự Lực Văn Đoàn ended in 1942 to avoid talking about what happened after.”

At that time, France was in an inferior position during World War II, and then Japan invaded Vietnam, making the colonial government even weaker. A series of secret organizations were formed with the aim of gaining independence. Thạch Lam, Tú Mỡ and Thế Lữ were not politically active, while Nhất Linh, Khái Hưng and Hoàng Đạo formed their own party. They later joined Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng, one of the non-communist parties.

From left to right: Nhất Linh, Khái Hưng, Hoàng Đạo.

Huynh said: “To tell you the truth, at that time the Vietnamese revolution was very complicated. Everybody said they were patriotic, but they were patriotic in their own way. All parties wanted to fight for independence, but this one wanted to crown a king, that one might want a prime minister, the other wanted a head of state, each had their own way.”

With their difference in ideals, the parties got so divided that eventually the Vietnamese not only fought the French, but also each other. In his last novel, Giòng Sông Thanh Thuỷ, Nhất Linh wrote about his revolutionary activities in Vietnam and China from 1944–1945, the time when tensions between Việt Quốc and the Việt Minh came to a murderous boiling point.

Photo via Quán Sách Gia Trinh.

This was also a time of decline for the Group. Phong Hoá had stopped publishing for several years after being accused of mocking the government. Ngày Nay, their "backup" newspaper in case Phong Hóa was suspended, originally focused on social issues, then became a propaganda tool for Việt Quốc. The Group’s time of writing freely had come to an end.

In 1945, the August Revolution succeeded. All the parties temporarily sat together to create the Government of Resistance Coalition, with Hồ Chí Minh at the top. Remembering this time, Tú Mỡ once wrote: “[In the new government], anh Tam [Nhất Linh] was the Minister of Foreign Affairs, anh Long [Hoàng Đạo] the Minister of the Economy. I was happy, Tự Lực Văn Đoàn may be together again. But I was wrong...”

It’s hard to know everything that happened. Not long afterward, Nhất Linh resigned and left for China. Khái Hưng was captured and executed by the Việt Minh after the Ôn Như Hầu incident. Hoàng Đạo died suddenly on a train in China, and his family is still unsure whether he was poisoned or not. Later on, Nhất Linh also drank poison and killed himself.

From left to right: Tú Mỡ, Thế Lữ, Xuân Diệu.

And so among the seven of Tự Lực, only Tú Mỡ, Thế Lữ, and Xuân Diệu lived until old age. The others were called traitors, and their descendants had to flee the country. That is why the tragedy still resonates to this day. Fortunately, the most valuable thing that Tự Lực created, their văn sản, or literary wealth, lives on.

Of the seven members of Tự Lực, only Xuân Diệu was honored with a street in Hanoi. Photos by Linh Phạm.

The book Hà Nội Băm Sáu Phố Phường is an anthology of all the newspaper pieces that Thạch Lam wrote, which were published one year after he was gone. The book has 22 chapters, among which 16 are about the cuisine of Hanoi. But Thạch Lam didn’t just simply write about food, he also described the affection that an opium addict harbors for a piece of giò, or the happiness of a cart driver sipping wine, or the way that the courtesans ate bún ốc: “The sour broth wrinkled the tired faces, the hot pepper burns the wilted lips, and sometimes makes them drop a tear that is more honest than any shed for love.”

Through food, Thạch Lam talked about the daily life of the Vietnamese. In the book's foreword, Khái Hưng writes:

When Thạch Lam wrote about “the tiny souls living in the dark,” he contributed to that which Khái Hưng called dã sử, or history written by the people. This part was what made me cry. I became a writer because I want to write down the things I see and hear. And from deep within my soul, I felt the longing to follow in their footsteps.

The headquarters of Tự Lực at 80 Quán Thánh was an imposing villa before, but is now obscured by shops and a bank.

Both Martina and Huynh asked why I cared about Tự Lực. I didn’t have a good answer then, but it is much clearer now. I tell their story to show my respect for the ones who built our quốc ngữ literary wealth, the ones who inspire me to keep on adding to the dã sử of this country.

This feature was first published in May 2022.