Perched on top of a hilly area, Da Lat's Cao Dai temple is a towering structure of vibrant aesthetics and intriguing mysticism.

Read the article in Vietnamese here.

A common tour schedule for tourists in Saigon often includes a day trip to the tunnels in Cu Chi and Tay Ninh’s nearby Cao Dai Temple. Da Lat also has a large Cao Dai Temple, yet it rarely appears on people’s misty mountain town travel itineraries. Perhaps the hoodied hipsters are too distracted snapping selfies in front of yellow walls, bemoaning their inability to gaze at "repugnant statues," or sussing out the best bánh mì xíu mại. Saigoneer, however, was curious to bypass the more conventional tourist stops and took the 10-kilometer cruise out of town to the Da Phuoc Temple.

Cao Dai is a young religion; its founder Ngô Văn Chiêu established it in the 1920s. Born to a destitute family, Chiêu eventually became a bureaucrat in the French-Indochinese government and developed an interest in spiritualism, in addition to the Confucian principles he was raised with. In 1920, when working in Phu Quoc, he claimed the Supreme Being spoke to him on numerous occasions. Upon his return to Saigon three years later, his belief in the need for a religion that unites all other religions, as informed by his discussions with the Supreme Being, led him to attract other followers, many of them Vietnamese working in the colonial administration.

In 1926, Chiêu and 28 followers, including a man named Lê Văn Trung, who had experienced similar visions, signed the official doctrine of Cao Dai. Chiêu returned to the more secluded life he was accustomed to while Trung became the religion's first pope as it developed an administrative structure similar to Catholicism.

From there, the religion spread throughout southern and central Vietnam, with numbers growing to one million by the outbreak of World War II. In the conflicts that followed, it undertook militaristic and political activities that were dismantled by America and its allies. It wasn’t until 2007 that it was granted legal recognition and unrestricted rights to practice, with an estimated four to six million followers today.

A running theme in the history of Cao Dai is skepticism about, or outright dismissal of, the religion, particularly by western observers. This view continues today, as exemplified by a Qantas in-flight magazine published in 1999, which describes its adherents as belonging to a “cult” and disparages the interior of a temple where “saccharine pink clashes brazenly with Tiffany blue.” It’s difficult to imagine such language being used to describe other religious sites.

Thanks to its relatively recent founding, unlike more ancient religions, outsiders often consider Cao Dai’s tenants to be bizarre. The synchronistic religion merges elements of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism while also honoring aspects of Spiritism, Brahmanism, Islam, and Christianity while believing a singular god with numerous prophets and visionaries. Its professed fundamental principles include followers honoring their “duties towards themselves, their family, their society (a broader family), then toward humanity (the universal family); the “renunciation of honors, riches, and luxury”; the “adoration of God, the veneration of Superior Spirits and the worship of ancestors”; and the “existence of the spirits and the soul, their survival beyond the physical body, and their evolution by successive reincarnations, according to the Karmic Law.”

These principles, contained in the Buddhist, Confucian and Taoist teachings that Cao Dai draws from, are hardly outlandish. Yet, the religion has sometimes been viewed, especially by the west, as bizarre thanks in part to their inclusion of saints such as Shakespeare, Victor Hugo, Jesus, Muhammad, Moses, Joan of Arc, Louis Pasteur, Sun Yat-sen, Lenin, and Vietnamese poet and prophet Trang Trinh. Despite sharing most religions’ core precincts of unselfish love and justice, Cao Dai’s inclusion of these modern figures, its very newness, as well as the historical and political events that have surrounded it, have led some people to see it as intrinsically stranger than many other religions.

An example commonly cited by cynics to delegitimize Cao Dai is its temple’s architecture and aesthetics. In his 1953 Indochine Report, British writer Bernard Newman wrote of the Cao Dai Cathedral in Tay Ninh: "The designers of the Festival of Britain would love it: so would Walt Disney." Graham Greene concurred in The Quiet American, calling it “a Walt Disney fantasia of the East, dragons and snakes in technicolour.” Such descriptions continued well past Vietnam’s Doi Moi era that ushered in greater interaction between Vietnam and the west, including a 1993 article in National Geographic that stated: "The temple itself is a Disneyesque expression of the sect's childlike borrowings from the world's religious experience. Bleeding heart statues of the sacrificed Christ, long Confucian beards, flabby, smiling Buddhas and vast pillars swathed in a confection of dragons all conspire to convince the unsuspecting visitor that he has stumbled upon a museum of religious waxworks."

The use of dramatic color, exaggerated statues, ornate decorations, and a propensity for opulent scales are, of course, nothing new to religious structures. Rather, they can be found in some of the most famed and revered churches, mosques, synagogues, and temples around the world. Cao Dai communities, however, do not benefit from the great economic power of other religions, which results in Cao Dai buildings necessitating cheaper construction and materials, which may contribute to the unfair disparagement.

At 1,627 square meters, Da Lat’s Da Phuoc Temple is one of the largest of the nation’s 1,300 Cao Dai temples. The first altar was built in 1938 and helped grow the religion in the region to its present-day size of approximately 80,000 followers. Construction of the current structure began in 2005 and was completed in 2010 at a cost of VND7 billion (US$303,429). It was modeled after the Tay Ninh temple.

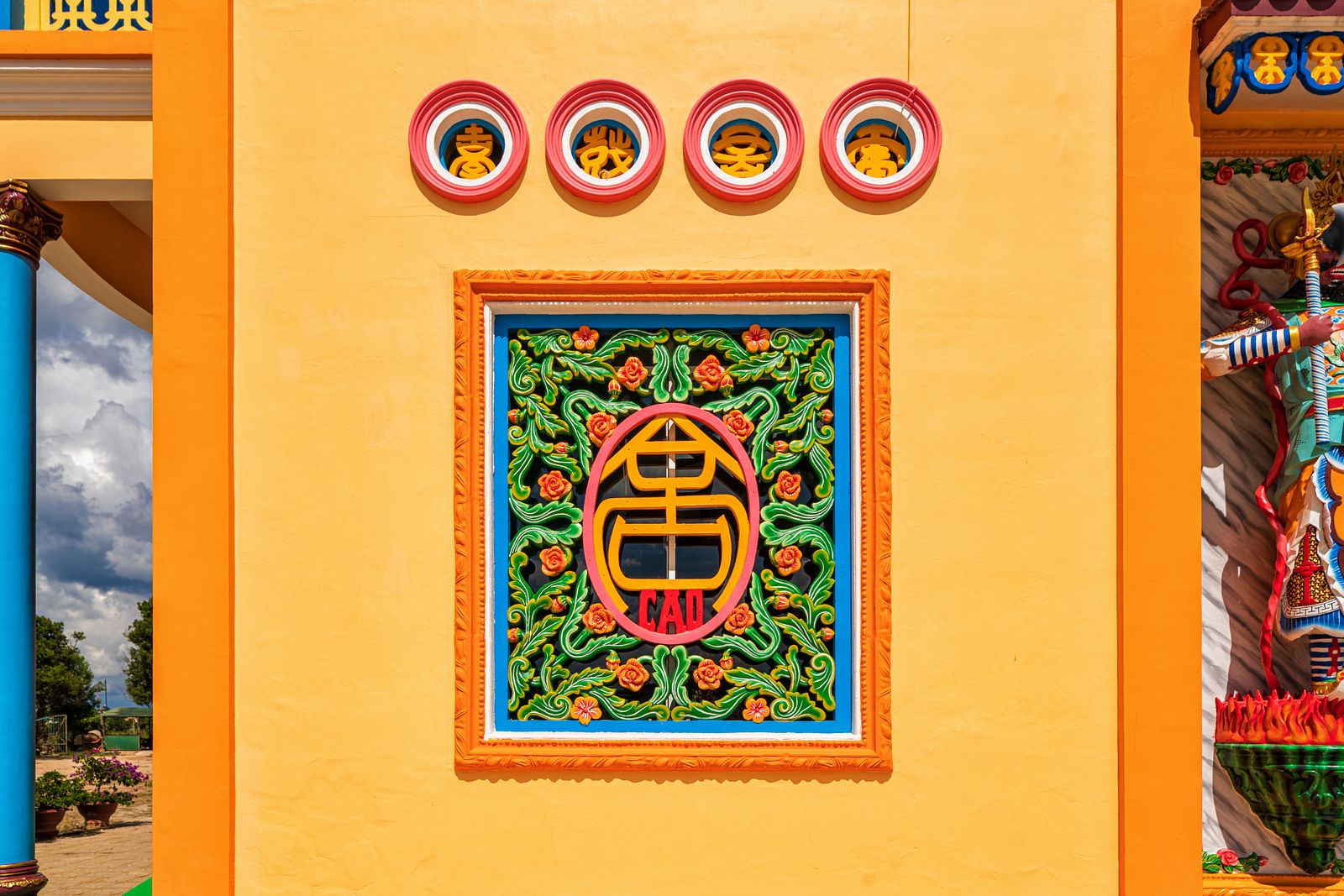

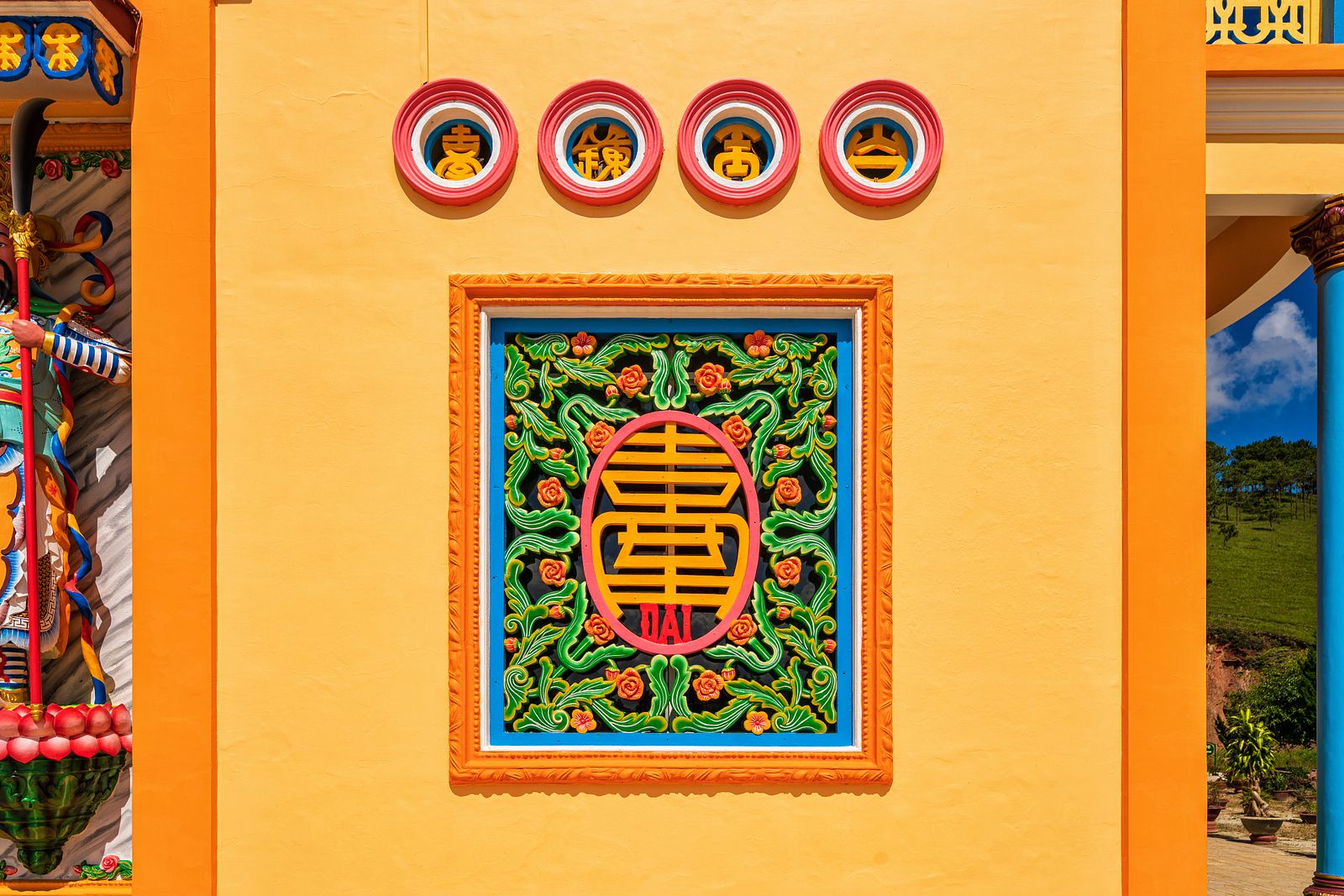

Da Phuoc stands on the top of a hill and thus makes an imposing impression upon approach. One immediately notices the building’s four large Dragon Flower pillars that represent the states in a period of human evolution according to the religion. Inside, a drawing, known as the Cân Công Bình image, depicts a hand holding a scale over the world symbolizing justice. The walls and pillars' bright colors that outsiders discredit as akin to cartoon animation, in fact, have important meaning with yellow representing Buddhism, blue for Taoism, and red for Confucianism. The temple also features a large painting of the Thien Nhan, or Divine Eye, the most important image in the Cao Dai religion, symbolizing the all-seeing divine. It serves to remind followers that God is watching over the entire world and that one must in return remain mindful of oneself to follow religious teachings.

Nearly every structural and design element in the temple has a metaphorical meaning. From the dragons wrapped around the interior pillars to the number of steps leading to different levels to the building’s overall orientation relate to core beliefs or elements of the various traditions that Cao Dai draws from. One doesn’t need to understand them to appreciate a visit, but it is necessary to acknowledge that this is not some slapdash aesthetic, but rather one reflective of specific and important foundations of the religion.

Plenty of scholarship has been written about the fascinating history, beliefs, and modern-day status of Cao Dai, including its meaning-laden architecture. One need not familiarize themselves with it before visiting a temple in Da Lat, Tay Ninh, or elsewhere, though it makes for a more enriching experience. As long as the visit is conducted respectfully, the quiet, spacious grounds and striking structures provide a serene environment to walk around and embrace silence and unique aesthetics, with some beautiful views of the countryside on the way.

Da Phuoc Temple | Tu Phuoc, Ward 11, Da Lat, Lam Dong Province