The story of Vietnam and cọp is not one where we will come out looking good.

In just a few days, the beginning of February 2022 will also usher in the start of a Year of the Tiger. If this was any other zodiac animal, many prospective parents would be looking at their desk calendar with bright eyes, marking out dates and mulling over schedules for a new member of the family. Tiger years, however, carry with them an ancient superstition that it will produce a batch of baby girls who grow up and become hard to marry. Some traditional schools of thought believe newborns are destined to take after characteristics of their zodiac animals, and tiger daughters will turn out too stubborn, feisty or independent. Of course, this is utter hokum, because there’s no divine force at the universe’s crafting table assigning romantic mishaps to babies, and I am relieved to hear, at least within my social circle, that the old wives’ tale is on its last legs in 2022.

As ludicrous as that might be, it does provide crucial insight into Vietnam’s complicated relationship with cọp, from the primordial days of wilderness exploration until now. Characterizing the dynamic as “complicated” is, in all honesty, merely a way to assuage my own personal guilt and secondhand embarrassment at mankind, because it’s really quite simple: we fear tigers and we hunt them to extinction.

King of the Asian jungle

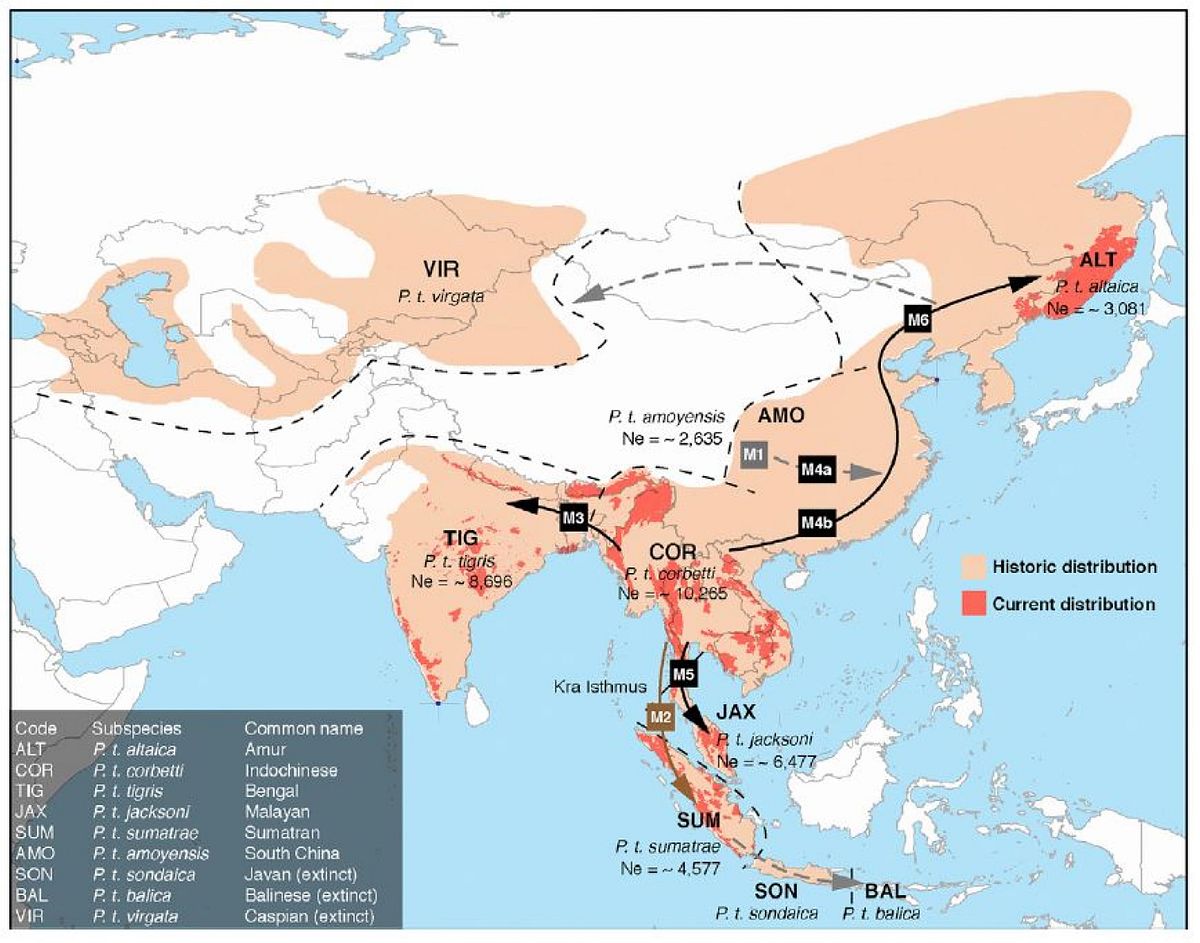

Map via The Conversation.

From the early 20th century until now, worldwide, tigers have lost over 93% of their historic range, and the figure is increasing as we speak. Tigers, or Panthera tigris, are native to Eurasia. Once upon a time, their fluffy white paws treaded vast stretches of land, from Turkey in the west to the Russian Far East, and as far south as Bali, Indonesia. At the moment, only some small separate pockets of cọp persist in the Indian subcontinent, Myanmar, Thailand, Sumatra and Siberia. Scientists recognize two main subspecies of tigers today: Panthera tigris tigris in continental Asia, and Panthera tigris sondaica on the Sunda Islands of Indonesia.

Perusing the familial behaviors of cọp, it will become apparent to anyone that it’s no misfortune to take on the attributes of these loyal creatures, if we were to accept the absurd hypothesis of the zodiac baby theory as true for a moment. In his observation of tigers, mammalogist George Schaller noticed that “an adult [tiger] of either sex will sometimes share its kill with others, even those who may not be related to them.” A male tiger will share a kill with females and cubs, and even allow them to feed on the meat before he’s done with it. This is remarkably amicable compared to the competitive and hierarchical behaviors exhibited in prides of lions. A strong will, confidence, loyalty and respect for the family — these tiger qualities are valuable personality traits that would surely benefit any Vietnamese baby regardless of their gender.

A strong will, confidence, loyalty and respect for the family — these tiger qualities are valuable personality traits that would surely benefit any Vietnamese baby regardless of their gender.

The Indochina Peninsula is home to the Indochinese tiger — smaller than its temperate and Indian cousins, but no less mighty. They mainly live alone across expansive areas marked by their uniquely pungent urine, but can be spotted sharing meals with their kin. In Vietnam, the last wild cọp was spotted in Pù Mát National Park in 1999, according to park director Trần Xuân Cường; none has been detected since, and no breeding population exists in neighboring Cambodia or China. Thankfully, Thailand and Myanmar maintain the last strongholds of Indochinese tigers in the wild, hosting around 160 and 85 individuals, respectively.

One who shall not be named

Vietnam’s relationship with cọp initially formed on a foundation of fear, and this fight or flight response has colored how we view these apex predators for hundreds of years. As ancient Vietnamese moved southwards, slashing jungles and putting together settlements, we encountered tigers for the first time. Aghast was the first man who stared into the deep abyss of the jungle just to see it stare back. It didn’t make a sound, but its presence could be felt on his skin, prickling like an invisible rash. Every sound seemed to take on a sinister timbre. His blazing torch might protect him at that moment, but it couldn’t stop livestock from disappearing overnight. During the age of exploration, tigers embodied the most heightened tension of the man versus nature conflict, a savage unknown that encompasses both the mortal danger and enthralling majesty of the wilderness.

During the age of exploration, tigers embodied the most heightened tension of the man versus nature conflict.

Across the Mekong Delta, cọp mythology is rampant. Elders recall stories of their fathers’ brush with the beast. Villages build shrines for local tigers to pray for safety and put up offerings in hopes of appeasing them. An Giang legends whisper the mysteries of Thất Sơn, a clump of seven local mountains said to be the nesting ground of a pack of demonic white tigers. Many communities adopted alternate terms for cọp, some of which still circulate today, like “Ông Ba Mươi” or “Ông Kễnh,” to avoid addressing them directly, as if they can somehow know when you dare speak their name and will materialize to Avada Kedavra you to an excruciating death.

Because of the mystic reputation of cọp as powerful preternatural beings, to fight a tiger and live to tell the tale is viewed as the ultimate act of strength, and more often than not, masculinity. Phùng Hưng, a war general living in northern Vietnam in the 700s CE, was the first historical figure widely known for allegedly defeating a tiger.

A tiger mural at the Temple of Literature in 2014. Photo by Erwin Verbruggen.

Tiger statue at a temple in Bắc Giang Province. Photo by Bùi Thế Tâm.

A tiger effigy at a shrine in Long Xuyên, An Giang Province. Photo by Bùi Thụy Đào Nguyên.

A predated predator

Manhandling a sterling hunter like cọp is no easy feat, past or present, but even with their sharp canines and brute force, tigers were no match for the collective intelligence of humans. Sooner than later, Vietnamese communities were no longer fighting tigers to defend vulnerable villages or out of self-defense; the act took on a malevolent connotation when it became purposeful.

In Thủy Biều Ward, just three kilometers from central Huế, stands a curious circular structure made up of two walls of bricks, the inside taller than the outside. Five small entrances open into its center. The words “Hổ Quyền” are carved over the opening. It was at this miniature colosseum that past emperors and royals watched barbaric fights between elephants and tigers for fun. Built in 1830 under the rule of Emperor Minh Mạng, first as a training ground for war elephants, the stone structure over time became a place for gruesome entertainment. You can read our past Natural Selection on voi to find out more.

'Thư hùng' by Tuấn Dương. Photo via Phanxipăng.

The practice of organizing fights between voi and cọp even predated the arena, which was only built later for convenience. One particularly harrowing bloodbath took place before Hổ Quyền was a thing, under Lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát in 1750, in which 40 war elephants demolished 18 tigers. That would probably amount to the entire population of living Indochinese tigers in Indochina today. The last arena fight happened in 1904 under the rule of Thành Thái, though the structure still exists in Huế nowadays.

There are no proven therapeutic benefits to using tiger bones for any kind of treatment, but that has never stopped poachers.

Capturing cọp for entertainment slowly gave way to hunting them for commercial gain in the 20th-century. Their bones are the crucial ingredient for a prized remedy in traditional Chinese medicine that has also gained popularity among certain strata of Vietnamese society, where it’s known as cao hổ cốt. There are no proven therapeutic benefits to using tiger bones for any kind of treatment, but that has never stopped poachers from ransacking jungles across Asia to satisfy the prestige purchases of their insatiable customers.

A reversal of man versus nature

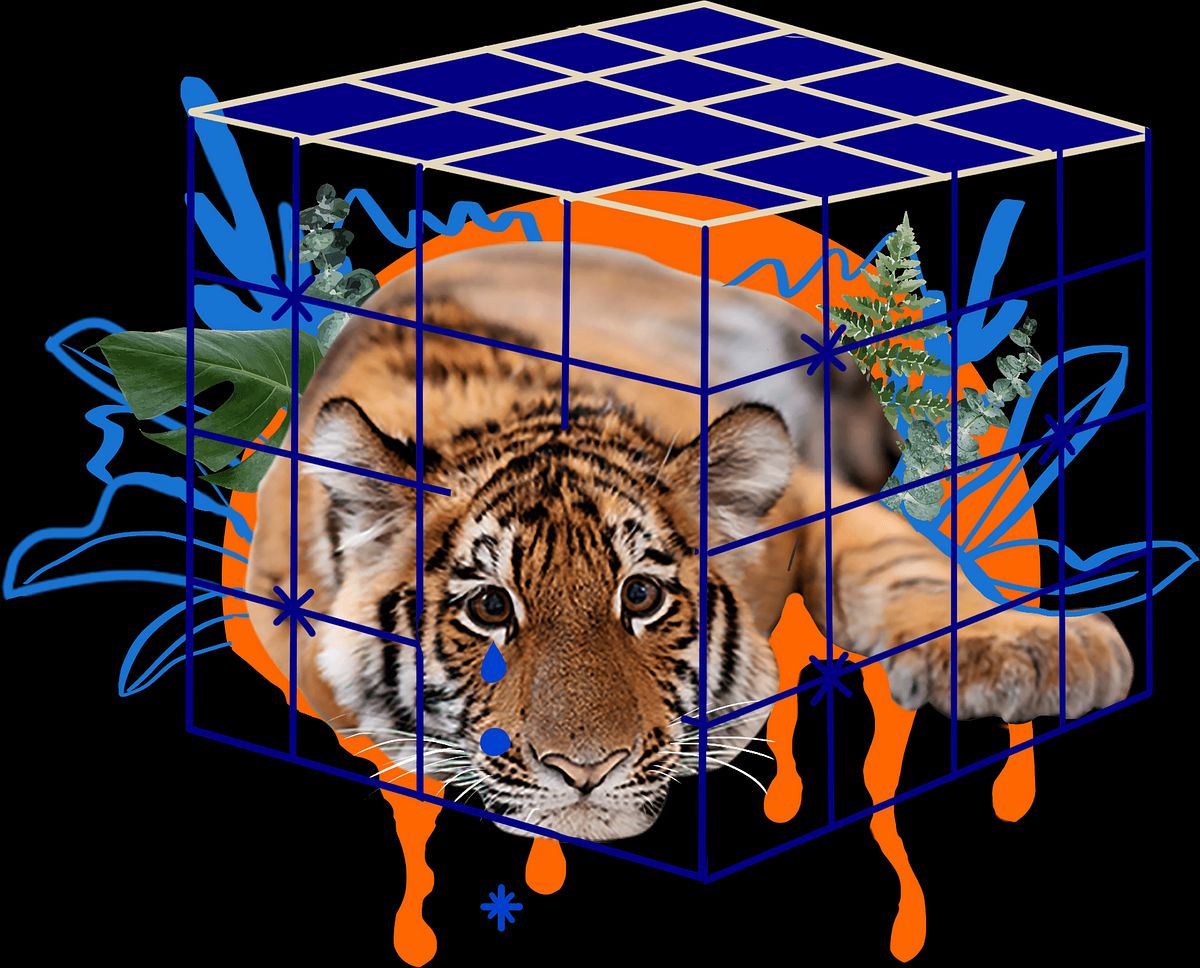

That brings us to today, when Panthera tigris as a whole is listed as “Endangered” on the IUCN Red List and the remaining Indochinese tigers in Vietnam live in rescue centers. 2021 was a particularly fruitful year for wildlife law enforcement officers. In August, Nghệ An police caught two individuals carrying seven tiger cubs in their car on the way to a buyer; the baby cọp are being taken care of by conservationists at Pù Mát. Just a few days later, in the same province, police discovered 17 adult tigers being reared in pens like garden-variety pigs at a local house. Tragically, eight died shortly after being rescued, though the remaining nine are healthy and being housed at an ecological tourism complex. The owners confessed that the tigers had been smuggled from Laos as cubs and had lived in their house since.

It is a baffling task trying to figure out the motivations behind the perpetrators’ desire to raise captive cọp, though for whatever reason, it couldn’t have been out of goodwill, judging by the squalid underground cages and severely malnourished victims. The rescue animals have escaped a gruesome fate as ingredients for some rich dude’s rice wine brew, but are unlikely to return home, as most tigers who grew up captive face difficulties fending for themselves in the wild. They have long associated humans with food, so will not shy away from human settlements and the threats of poachers. The next best option for trafficked tigers lies in rescue centers, animal sanctuaries and, less ideally, zoos.

The Hanoi Wildlife Rescue Center is currently sheltering the largest population of tigers in Vietnam, with 36 felines of varying genders and ages, all rescued from traffickers. The tiger exhibit at the Saigon Zoo has eight: three Indochinese tigers and five Bengal tigers. Lương Xuân Hồng, director of the Hanoi center, harbors great passion for animal rehabilitation, to the point that he does cardio training to be able to keep up with trips into the mountains to release caught animals to their natural home. Hồng’s great dream is “to return the tigers back into the wild,” but unfortunately “there isn’t a jungle in the entire country that’s suitable to protect tigers.” To the center’s credit, their resident cọp all have affectionately selected names, a proper diet, enrichment items, and veterinarian care, so it’s safe to assume they’re as happy as can be for animals in their predicament, when the alternative is falling prey once again to poachers in their natural habitat because they were taught not to fear humans.

And here lies the fatal flaw in cọp’s beautiful creation: they evolved to not fear anything, to roam and to reign without a care, but their natural selection process did not account for the fast and furious rise of another apex predator: humans. For centuries, we were deadly frightened of tigers for our survival, but perhaps it is time for the reverse. Cọp ơi, I beg of you, avoid humans like the plague. Another Year of the Tiger is peeking over the horizon, and it surely won’t be a year when we can vanquish tiger poaching and trafficking. One can only desperately hope that by the time the next cycle rolls around, there will still be live Indochinese tigers kicking about, puckering their whiskers and roaring into the deep abyss of the jungle.