Back in 2014, amid the weekly cycle of news, a particular image was more striking than most: Doctor and Professor Ngo Bao Chau stood in the middle of a makeshift classroom in a rural village in Thai Nguyen Province while teaching local kids.

Chau is a Vietnamese-French mathematician who’s currently based at the University of Chicago, USA, and the first Vietnamese awarded with the Fields Medal for accomplished mathematicians. While Chau’s accolades are impressive, what tickled netizens the most upon setting eyes on the set of photos were his shoes — a pair of beige dép tổ ong, Vietnam’s unofficial national footwear.

Doctor Ngo Bao Chau teaches students while wearing dép tổ ong in Lung Luong Primary School in Thai Nguyen. Photo via SaoStar.

Since his attainment of the Fields Medal, Chau has become something of a symbol of Vietnamese excellence on world stages, which was why some were surprised that someone of the doctor caliber could comfortably be seen with dép tổ ong, a humble icon that occupies the other extreme in the scale of glamor: hardship, poverty and difficult past eras.

This is not to say that Vietnam is ashamed of dép tổ ong. We wholeheartedly embrace them the way we would a long-lost relative, or a reminder of our relationship with childhood and economic austerity. In some ways, one might opine that the footwear could be seen as a symbol of Vietnamese excellence as well, what with its survival for almost four decades.

Dép tổ ong, which translates to “honeycomb slippers,” is neither fashionable nor imposing. It’s made of painfully beige rubber with a “thicker-than-life” sole and a strap featuring a hexagonal pattern that resembles a honeycomb. What the honeycomb slippers lack in style, they more than make up for in durability and functionality, as is the case with most goods produced during Vietnam’s Doi Moi years. This is also why nowadays the footwear is still a common item for children in the country's less fortunate regions, like northern Vietnam's mountainous provinces.

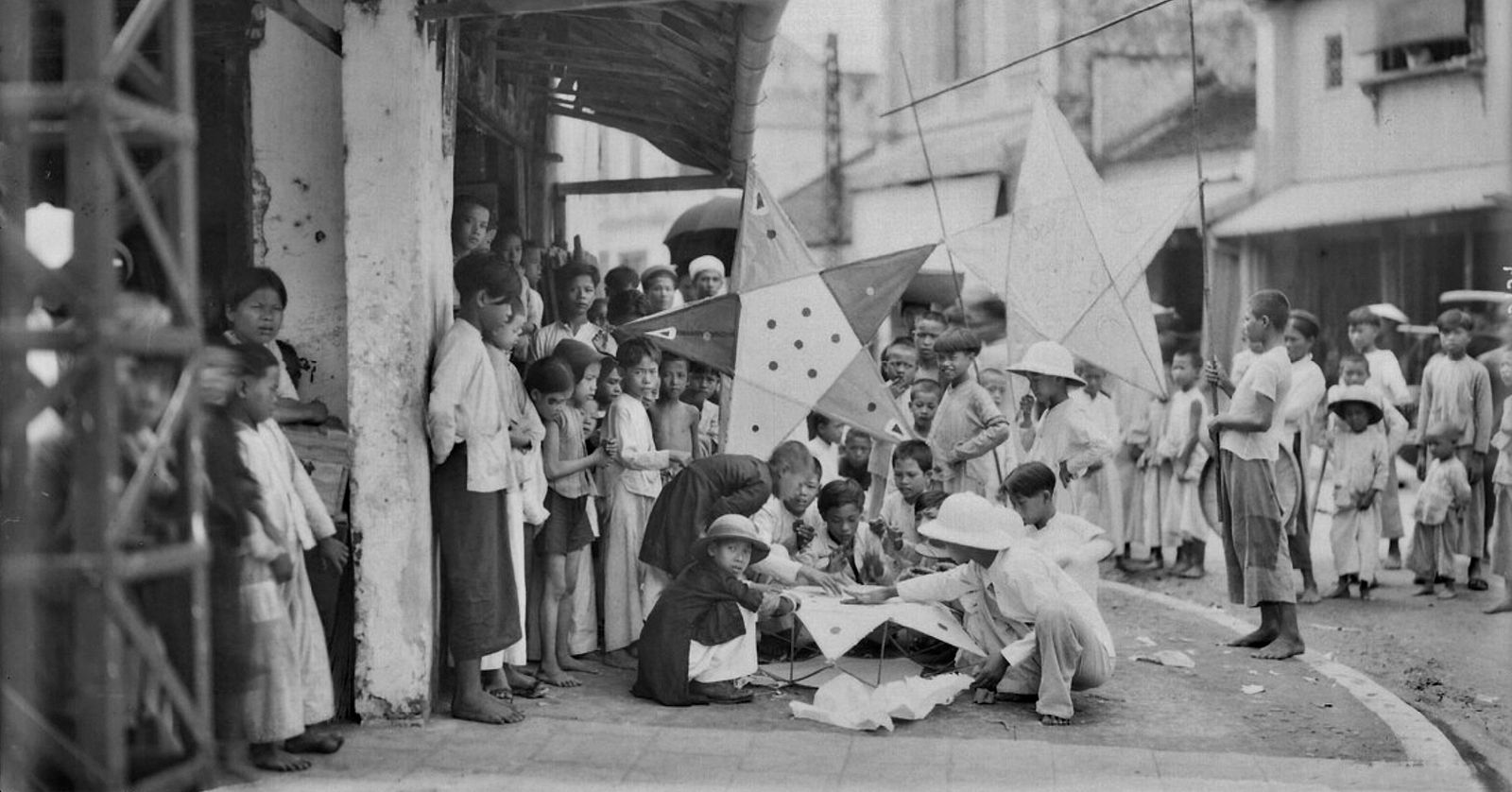

Children in poorer provinces in Vietnam are always in need of new footwear, and dép tổ ong works thanks to its durability. Photo via Ao Am Bien Cuong.

The first model of dép tổ ong was produced by the Hai Phong Plastic Workshop in the 80s under the brand Tien Phong. Tien Phong slippers were made from natural rubber in simple shades of eggshell and beige, which would progressively get darker with time as the slippers join their wearers in many life adventures. Every element in their design and production serves a purpose: rubber for sturdiness; a thick sole to resist the odd objects on Vietnam streets (which were more dirt than asphalt), and the honeycomb lattice which allows one’s feet to breathe in the punishing tropical heat.

Along with Miliket instant noodles and Thong Nhat bicycles, dép tổ ong gradually made its way into a clique of staple items in every family in Vietnam, especially in northern localities near Hai Phong. While the market saw the appearance of other brands of dép tổ ong, many deemed Tien Phong’s footwear to be the best of the bunch, and hence, the most expensive. A Zing reader recounts a memory from his childhood in 1987 when his mother had to sell 15 bunches of bananas to buy two pairs of dép tổ ong for his dad and himself.

Who would have thought that these unfashionable, plain slippers were once a must-have item in local street life? Today, each pair of dép tố ong sells for VND25,000–30,000, depending on the brand, country of origin and design. Mass-produced models from China are usually slimmer and gaudier with a range of colors on offer from magenta, midnight blue to neon. They’re also cheaper compared to domestically manufactured slippers, which are faithful to its timeless shade of beige.

A dép tổ ong rebranding project by designer Nguyen Duy Anh.

In an interview with Infonet, Dang Thanh Van, a branding expert, espoused the case of dép tổ ong as one of Vietnam’s most successful branding exercises.

“The enterprise could go bankrupt, get dissolved or disappear, but the ‘public perception association’ [to the brand] will take on a separate identity,” she explained in Vietnamese. “Even if they want to, brands are hard-pressed to shake off those associations.”

These entrenched impressions are indeed a challenge but were inevitable as the result of millions of people using the same handful of named products during those eras. At least in the case of dép tổ ong, years and years of brand recognition have sustained its popularity and survival well into the 2010s.

“Dép tổ ong, a low-brow product, is now deemed ‘never out of fashion’ by millennials because it can both satisfy the basic needs of low-income buyers (cheap, durable, comfortable) and resonate with the vision of younger customers (casual, down-to-earth, eager to express themselves in a unique way),” Van added.

In a decade when the kids of the 80s and 90s are now working adults in various fields as tastemakers, designers and entrepreneurs, it’s not a surprise to witness a resurgence of Vietnam’s past values and products in youth culture, and dép tổ ong is not an exception.

For Hanoi-based designer Nguyen Duy Anh, his pair of tattered honeycomb slippers reminds him of the 90s in the capital’s Old Quarter. Anh grew up in a multi-generation family and the first dép tổ ong he owned was an “heirloom” passed down the family from his cousins to his older brother and then to him.

“That pair of slippers was oversized, in the shade of cháo lòng, and tattered,” Anh recalls in an email to Saigoneer. “But to me, it wasn’t just footwear, it was also a shim for my uneven desk or wardrobe; something to throw at cans, use to mark the goal in street football; or even a weapon if needed.”

Old footwear, new animations.

In July, Anh published a new project on his Behance page that seeks to rebrand dép tổ ong in a sleek, yet playful way. The personal project, called TỔONG after its namesake, marries the slipper's timeless design with contemporary aesthetics, meaning minimal details, pastel colors and a tongue-in-cheek sense of whimsy. He started the project as part of a 2D Design Anthropology class, but decided to put his 3D modelling skills in practice too.

With TỔONG, the usually crude, dirty, unglamorous dép tổ ong is freed of its utilitarian fate to take on the role of liberated birds, quite literally. In Anh’s mock-ups, flocks of dép tổ ong gracefully undulate the screen in mesmerizing aerial formations that are reminiscent of synchronized swimmers, schools of fish, or actual birds. He also reimagined the honeycomb slippers as an ultra-modern brand in the vein of Apple or Pantone, using a color scheme of actual Pantone colors: ultra-violet, greenery and rose quartz were the company’s respective selections for color of the year in 2018, 2017 and 2016.

While the image of dép tổ ong is well-known in the psyche of Vietnamese, its technical specifications are surprisingly scant online so it was difficult for Anh to create the slipper’s 3D model from scratch. Nonetheless, the end result was a fascinating version of a classic icon. If dép tổ ong were timeless before, now it’s forever immortalized in the depths of the internet thanks to Nguyen Duy Anh’s TỔONG project.