There’s something for everyone during Tet Trung Thu season, as the arrival of mid-autumn comes with a wide variety of customs and traditional fare.

On the younger end of the age spectrum, lanterns have a timeless charm that appeals to children of all age. Teenagers and young adults, on the other hand, see these incandescent spectacles as the perfect backdrop for selfies to bolster their social media clout. Older Vietnamese are drawn to the diverse range of mooncakes in all shapes, flavors and sizes as gifts for family friends or work contacts.

While the subjects of lantern-making artisans might vary every year depending on which animated characters are popular at the time, some common motifs endure in lanterns and Trung Thu decorations across Vietnam. White rabbits frolicking on the moon, the lunar goddess Hang Nga and her willowy robe, the story of Cuoi and his magical banyan tree — these images have been indispensable components of the mythology surrounding Mid-Autumn Festival in the country for centuries. To celebrate this year’s Trung Thu, Saigoneer presents a brief summary of a few folk tales exploring the origin of the occasion. It’s fascinating that, despite the stories’ wildly different plots, many of them share a commonality: they all started from how ancient cultures interpreted the shapes of the moon’s surface.

The Story of Cuoi on the Moon

The first and only official record of the tale is in Kho Tang Truyen Co Tich Viet Nam, Volume III, a collection of local folk tales compiled by folk culture researcher Nguyen Dong Chi. Across decades, Chi collected and rewrote almost 2,000 Vietnamese folk stories, which were published into five volumes. The story of Cuoi is certainly among the most well-known of the tales, especially by children, due to its association with Trung Thu. It involves a lonely man sitting beneath a giant banyan tree, yearning for the days when he was living in contentment back on earth with his wife.

Once upon a time, there was a wood cutter named Cuoi. One day, while on his way to work, he comes across a family of tigers living next to a small stream. Upon seeing the tiger cubs, Cuoi turns violent and kills them with his ax, a burst of unwarranted aggression that would probably get him thrown behind bars today. He quickly hides when the mother tigress returns, devastated to witness the gruesome death of her babies. However, what happens next shocks him: the tigress feeds the cub some leaves from the nearby tree and they miraculously come back to life. After waiting for the tigers to leave, Cuoi digs out the entire tree and drags it home now that he has knowledge of its supernatural properties.

From that day, Cuoi becomes a notable healer in the region and saves countless lives using the tree’s leaves, perhaps as a way to assuage his guilt over the cruel killing of the tiger cubs. Among his saves is the daughter of a rich noble family, who drowns in the river. She is immensely touched by his altruism and asks to be his wife. A spontaneous proposal from a rich, beautiful woman? How could one say no? They get married and live happily ever after; except the happy ending only lasts for a few years. Cuoi’s wife is a beauty who takes care of him and makes him happy, but is unfortunately very forgetful. The magical tree grows luxuriantly in their backyard, but is very fussy about its sustenance: it only accepts clean water as irrigation.

One day, while Cuoi is away in the forest, his wife makes a grave mistake by…peeing on the tree’s root, despite his repeated warnings about the plant’s diva demeanor. Offended by the erring urination, the tree starts shaking violently, preparing to shoot off into the sky like a space exploration rocket. A rather extra, but justified, response to being pissed upon. Cuoi gets home in time to witness the commotion, but it's too late. He tries to cling onto its roots while it levitates above their home. Eventually, it lands on the moon, taking Cuoi along as the first man to walk and live there. Sorry Neil and Buzz, better luck next time.

Many raconteurs today point to the shape of the shadow on the moon — it apparently resembles a man sitting at the root of a giant tree — as the origin for the story. Of course, this is open to interpretation, but the story of Cuoi is nonetheless a sobering cautionary tale for modern agriculturists: if you manage to grow a magical tree, don’t pee on it.

The Goddess of the Moon

A depiction of Hang Nga by an unknown artist from the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). Image via The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In real life, the moon is a barren ball of rock, but in folk mythology, it’s a crowded land occupied by many creatures and deities other than Cuoi and his banyan tree. Known in Vietnamese as Hang Nga, Chang E is among the most prominent motifs used in designs aiming to evoke mid-autumn imagery. She’s usually depicted with black, perfectly coiffed hair; a flowing dress made of wind-blown silk; and beds of cloud under her feet — an otherworldly appearance meant to inspire praise and dazzle onlookers. Chang E is mentioned frequently in Chinese mythology and literature, most prominently in the ancient text Huainanzi, a collection of essays from before 138 BCE detailing the zeitgeist of the time in topics such as mythology, astronomy, literature, geography, science, philosophy, and more.

The story of why Chang E comes to inhabit the moon revolves around her relationship with her husband, Hou Yi, a sterling archer (Hau Nghe in Vietnamese). According to an account of Huainanzi in The Handbook of Chinese Mythology, at the time, there were ten suns, instead of one. Each sun shines for one day and then sets for the next nine days. However, one day, a disastrous occurrence threatens to destroy everything: all ten suns rise on the same day, scorching the surface of the Earth. The Jade Emperor, the king of heaven, urges Hou Yi to save the world by shooting nine of the suns, leaving only one. He succeeds, and all is well again.

Yi is rewarded with the elixir of immortality from Xiwangmu, or Tay Vuong Mau in Vietnamese, better known by the title Queen Mother of the West. Chang E steals the elixir, consumes it and flies to the moon alone. This is the earliest version of the story of Chang E, and also the most unforgiving. It depicts Chang E as selfish and opportunistic, while later versions contain much more sympathetic plot details that seek to explain her occupancy of the moon.

In another version, Hou Yi wants to share the gift of immortality with his wife and wishes for them to take the elixir together. Alas, before they could consume the potion, Fengmeng, one of Yi’s apprentices, breaks into their home on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month and attempts to steal it while Yi is not home. Chang E, in a last-ditch move to prevent Fengmeng from taking it, swallows the elixir and becomes a deity. Wanting to be close to her husband, she opts to live on the moon. From then on, every year on that day, Hou Yi makes a banquet with all of Chang E’s favorite pastries and fruits to commemorate the occasion. This becomes the base for today’s mid-autumn traditions of baking cakes and having a feast together with family and friends.

The Selfless Rabbit on the Moon

Leaked footage from the moon showing a team of rabbits hard at work making mooncakes. Image via Weibo user 东予薏米.

Apart from Cuoi and Chang E, the moon is also home to white lunar rabbits, a popular symbol of moon worship in Vietnam, China, Japan, South Korea and even India. This also has roots in the interpretation of the dark shapes on the moon. Vietnam’s folk beliefs surrounding the lunar rabbit takes after a story from Indian literature. If the chronicles of Cuoi and Chang E are filled with drama and human-led narratives, the story of the rabbit is much more didactic.

Once upon a time, a fox, a hare and a monkey live together as best friends in the forest. One day, in a bid to better understand the nature of creatures in the universe, Buddha decides to test the trio. He transforms into an old man dressed in rags and wielding a cane. He tells the three that he is hungry and needs help finding food. The animals happily oblige: the monkey nimbly swings across trees and brings him loads of fresh mangoes and bananas, while the fox heads to the river and comes back with dozens of fish.

The rabbit is embarrassed that he only eats grass and has nothing to offer to the old man. He instead tells his two friends to make a fire from branches. He wants to jump into the fire, offering himself as the meal for the old man, but before he could proceed, Buddha throws his stick into the fire and reveals his true identity.

“Please, do not be afraid. You see I am more than a beggar. And I see you, too. You are truly devoted and kind,” he praises the three animals for their kindness, and turns to the rabbit. "But Rabbit, your generosity is beyond compare." He tells the rabbit to never harm himself and carries it with him to the moon for safe keeping. "Here you will shine brightly forever and all will remember your generosity."

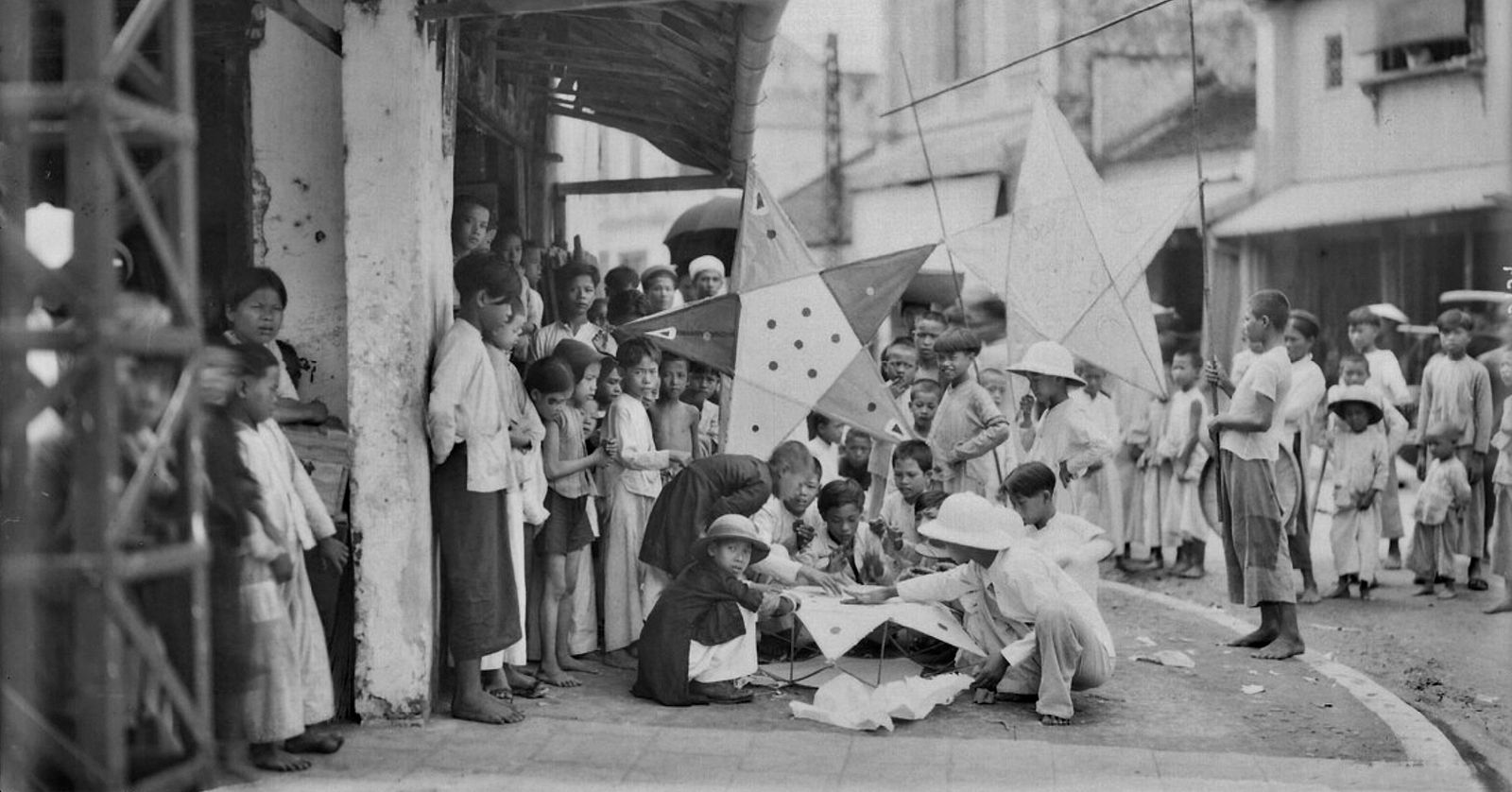

[Top image: A mid-autumn celebration in Hanoi in 1928/manhhai]