Is it a valid reverie or just mere misguided nostalgia to feel a sense of yearning for lives you’ve never lived?

The Saigoneer team is populated by a number of history nerds, and one of the artifacts that always resonates with us — and a significant portion of you, our dear readers — is vintage photos of past Saigon. Coming into existence in the early 1990s, I’ve lived through neither the tumult nor glory of the eras depicted in the photos, so at times I’ve wondered what a life in the 1970s would entail. How would the suds of Cô Ba soap feel on the calluses of my hands, what would Con Cọp root beer taste like, what would it be like to set foot into Tết amongst the cacophony and stench of firecrackers popping in the atmosphere?

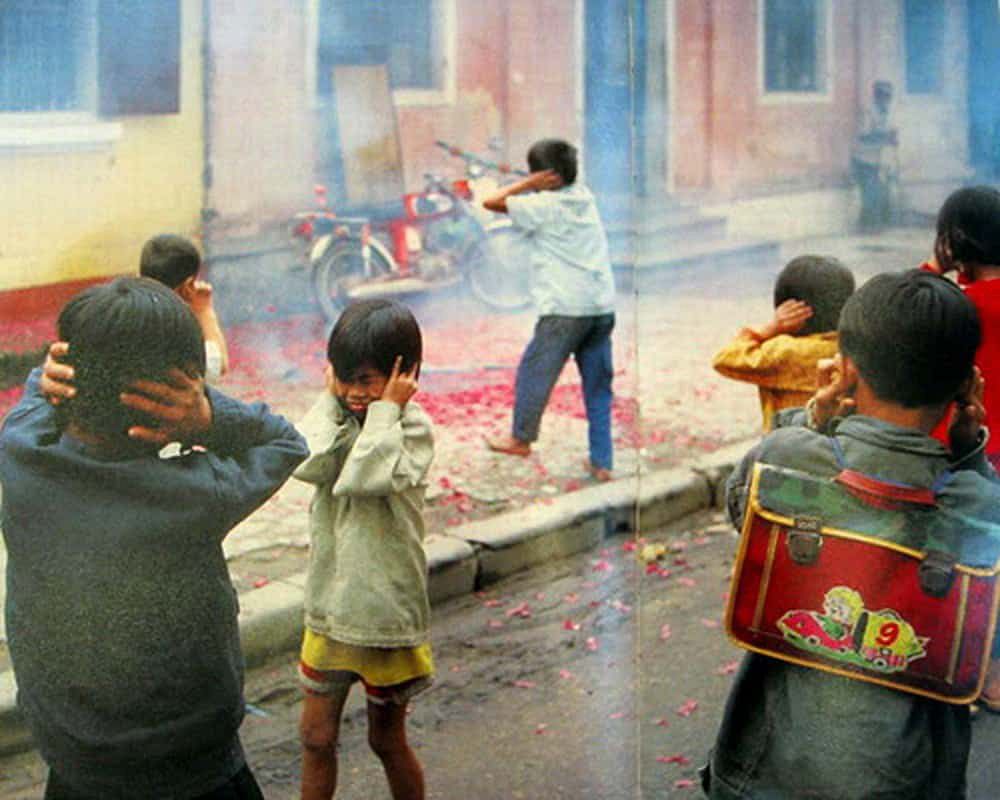

Firecrackers go off in front of a house on Hai Bà Trưng Street in 1992. Photo by Mark Hodson.

On August 8, 1994, then Prime Minister Võ Văn Kiệt signed the regulation to cease the use and sale of firecrackers across Vietnam, after centuries of the rudimentary pyrotechnic’s rule over the nation’s new year celebration. The ban came into effect on the first day of 1995, so for a few years, the existence of firecrackers and me overlapped. I probably spent a number of Tết, either bundled up in a crib or just old enough to teeter to hide behind my dad’s legs, with the pungent waft of gunpowder in the air; I just can’t remember them, so I can’t help but wonder. Even via old photos, lighting firecrackers didn’t seem to be a particularly enjoyable activity, beside its role as an evocation of Tết festivity. They were loud, stinky, and potentially dangerous — everything a reasonable Saigoneer today, especially one that’s averse to bombastic situations like me, would stay away from.

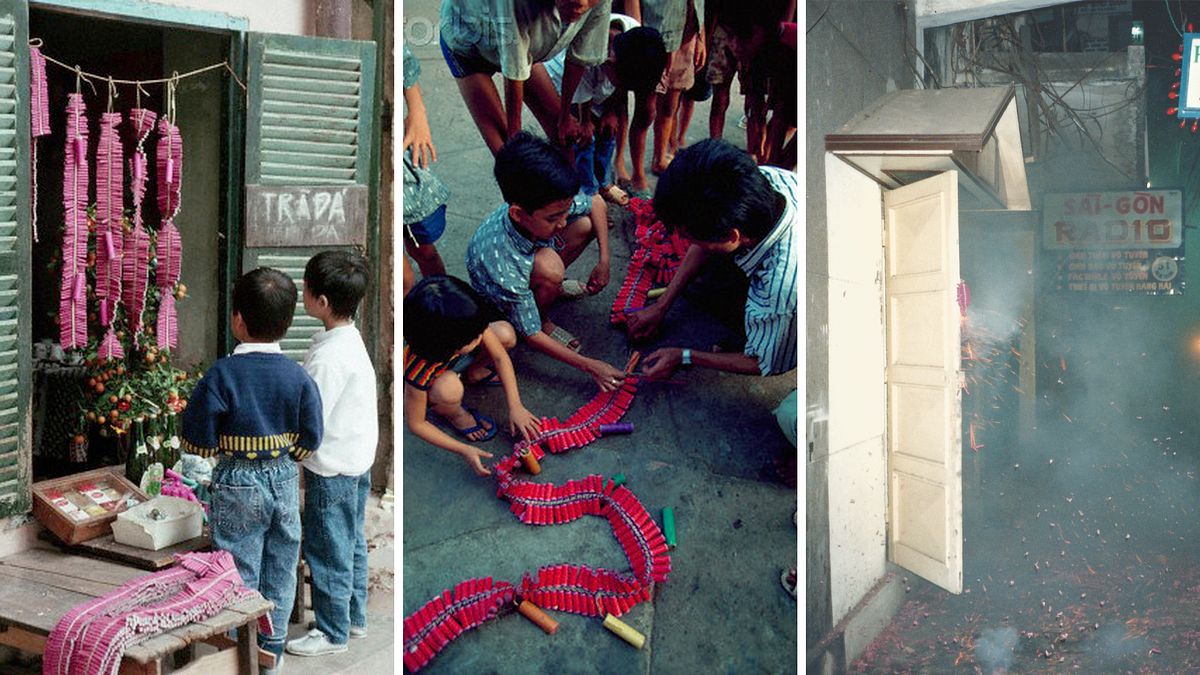

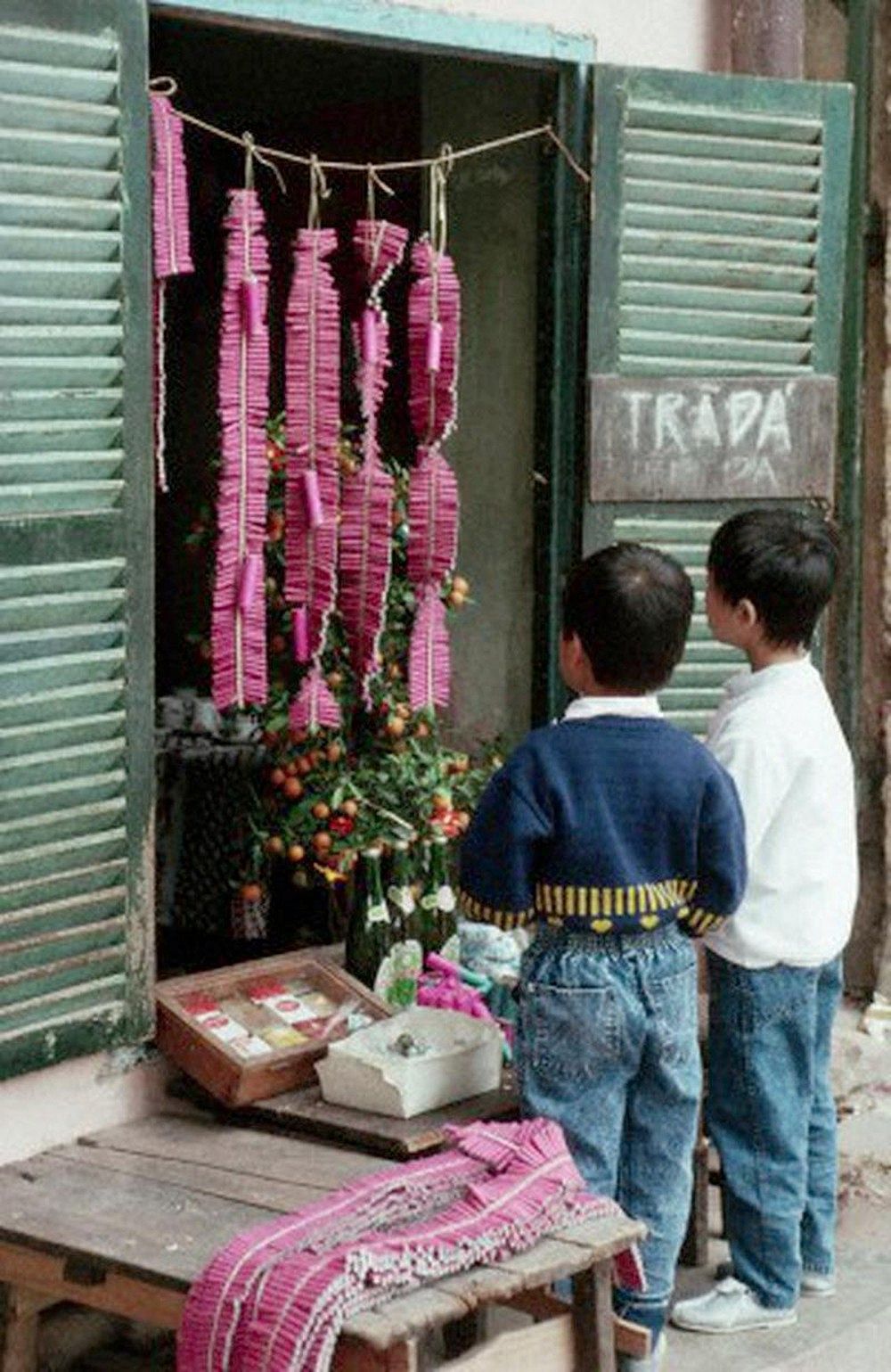

Children were always the demographic most amused by firecrackers.

Vietnam’s brush with firecrackers somewhat dovetailed with my own family history: my mother used to be in charge of “selling” firecrackers at the co-op. I use the verb “sell” in its loosest meaning, because, while we bid farewell to the planned economy in the late 1980s, firecrackers were still provided by the government and, for Tết, each family was only entitled to “buy” one meter of firecracker string, in addition to mứt Tết, rice, and a kilogram of pork. Those not interested in the decorative fire hazard could pass their portion to other households at a price.

She often speaks of firecrackers with a tinge of annoyance in her tone, lamenting their tendency to bring out the worst of human behaviors. Teenagers often threw seemingly unexploded tubes at passersby just for shit and giggles; my dad was hit by stray firecrackers while riding around town many times. Lighting unexploded firecrackers was a common new year game for kids, who dared one another to hold lit firecrackers for as long as possible, as if they were in a Tom & Jerry episode. Every Tết, hundreds of burn cases and other fire-related accidents flooded local emergency rooms, which at times hosted kids and adults with whole fingers blasted off — it was probably a wise idea to extinguish the reign of firecrackers in Vietnam for good.

Loud noises, be it from firecrackers or karaoke boomboxes, are a Tết delicacy.

I live vicariously through a lot of things: vintage albums, my friends’ Instagram feeds, novels set in lands as far and strange as the mind can dream up; but perhaps my favorite mother lode of vicarity is via stories told by those who have lived vivid lives. It is only through stories like these that I could learn to put to rest my secret longing for firecrackers. This Tết, there won’t be any whiff of burnt gunpowder at my house, but as we convene around a bánh chưng or two, the stories will live on.

Vignette is a series of tiny essays from our writers, where we reflect, observe, and wax poetic about the tiny things in life.