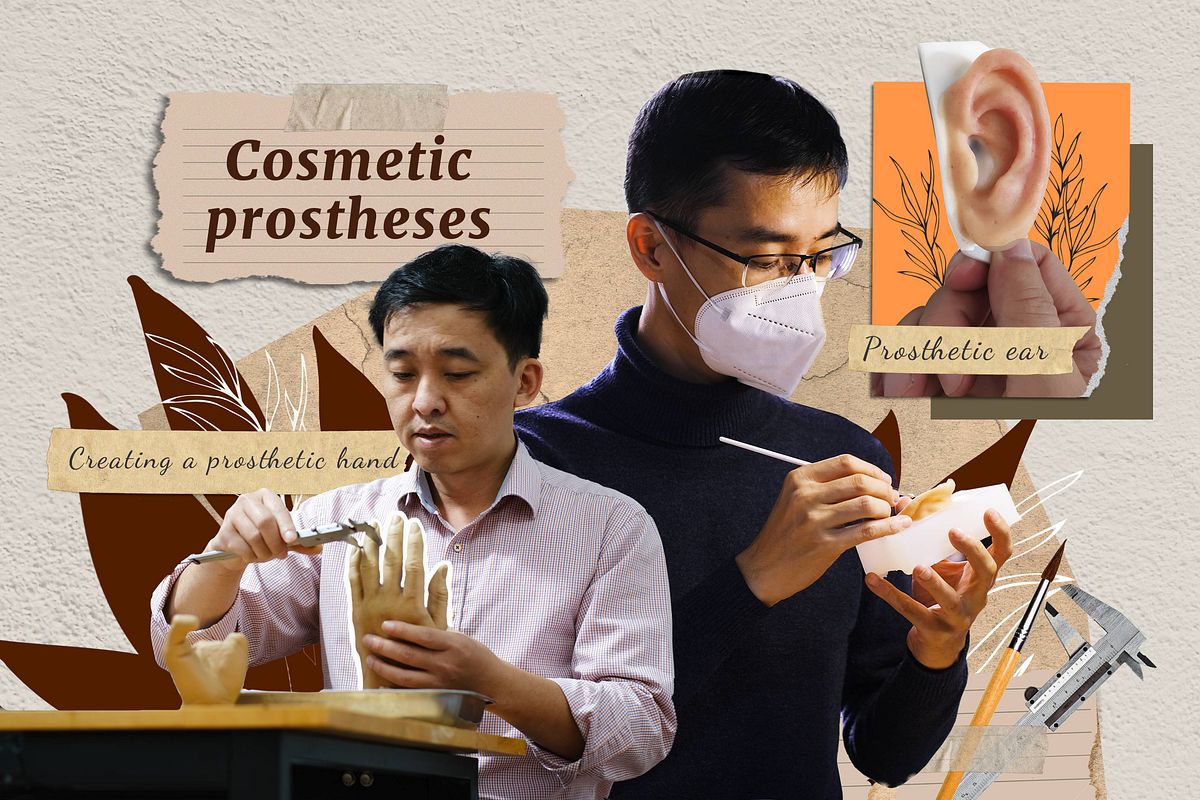

“The products we make are fake arms, legs, noses, ears…from silicone. The value we create is emotional healing, giving our customers confidence in themselves and their lives — the things they lack after surgeries,” Phúc shared while introducing their products.

It wasn’t hard for me to find Phúc’s office, though his space lay deep in a twisted alley of Hoàng Mai District, where the houses seem to be numbered randomly. The enthusiastic “tour guide” I had that day was Hiệp, Phúc’s partner for the last four years.

With a floor space of 12m2, the three-story house that they rent serves as an office, warehouse and showroom, as well as a workshop where they create prostheses like fingers, toes, ears and noses for people who have lost such body parts.

Phúc casting a mold for a hand.

Creating prosthetics is not a new thing in Vietnam. There are many factories with modern technology creating a diverse range of products from plastic, silicone, electronics, etc. These products can perform some basic functions like grasping or opening, but aesthetics and personalization are still not important factors.

Hiệp showed me two large plastic boxes containing sample products. At first glance, they looked quite like the costumes people buy for Halloween. He encouraged me to try on a prosthetic finger to get a feel for the material and adhesion of the product. It took me a while to find one with the same skin tone as mine, and Hiệp carefully showed me how to put them on and told me about the requirements of a prosthetic finger: “The most important thing is naturalness: looking natural and feeling natural. Most of our customers are those who have lost a small part of their bodies. The need for functionality is there, but it is not as important as aesthetics. From skin tone, shape, size, adhesion, to small details like nails, fingerprints, curls, etc., all need attention.”

Hiệp painting an ear.

I was most impressed with a jar containing 20 prosthetic noses that Hiệp and Phúc had meticulously created over three months for a girl in Lâm Đồng who was infected with the Whitmore “flesh-eating” bacteria. These noses looked similar at first, all had the fashionable L-line with a bright tone, but upon careful inspection, there were minute differences in hue and thickness.

Phúc explained: “The nose is the center of the face, so if we’re not careful, people will know it is fake. The girl also lives far away, so she only had two chances to come here for sampling and testing. We were determined to create many samples for her to try until we found a suitable shape and tone. Fortunately in the end we were able to make one that fit her well, and it is hard to recognize even without makeup covering the edge.”

Prosthetic fingers are best-sellers. Most customers lose theirs in workplace accidents.

Phúc and Hiệp’s customers are diverse, from those who suffer from accidents at work, at home, in traffic, to those with birth defects. Each has their own wound, but they share the same struggles: low self-esteem and loss of faith in life. I heard many stories that day, not only people’s names, their hometowns, their wounds and how they got them, but also their pessimistic feelings in the past.

About their special products, Phúc shared: “Our high standards for aesthetics and personalization are not just for the sake of beauty, but for the emotional needs. The pain of losing a limb will pass, but the fear and disappointment can follow them forever. Currently, the treatment process at hospitals’ orthopedic wards has barely addressed this issue. We’ve met many patients who are traumatized after their accident and treatment. Some people dare not to see their wounds for months, some run away from their family, some leave their work for fear they can’t fit in again.”

A prosthetic foot requires a natural look, as well as demanding precision to facilitate movement.

Due to the emphasis on personalization, the production process is not fixed. The basic initial steps are measuring and casting molds for the missing parts, then creating the right skin color for the customer. Hiệp explained: “The hard thing is that the skin doesn't have a fixed color, it changes with the weather, human activities, it fades overtime, etc. Furthermore, with clay and silicone, the colors when blended usually look different than the manufacturer’s instructions.” He shared an example: “One time, I was very happy with a prosthetic foot that I made. But when the person put it on, it was a cold winter day and they didn’t wear socks, the other foot was completely white. So the foot I made didn’t match at all.”

Hiệp said that the process from consultation to final product takes at least two weeks, and starting prices range VND1–3 million. But many times the cost for prototypes is five or six times higher than the price quoted to customers. After four years in this field, they have created hundreds of prototypes, a sacrifice for the most perfect product. When they first started, Vietnam did not have any private prosthetic workshops. There was no production process, and materials were rare as well. The duo had to research and experiment themselves. Prior to this project, Phúc had ample experience in silicone shaping, while Hiệp used to work as a testing technician. But when it comes to this particular field, that experience didn't help much.

A customer trying on a prosthetic ear.

Now, their production process is established and they have gained some recognition, mainly through word of mouth. Yet the duo still does everything themselves, from consultations and production to marketing and delivery. When asked why they haven’t expanded the business, Phúc explained: “It’s not that we don’t want to hire more people, it’s just that this work demands a lot of patience and fastidiousness. It is not an easy thing to find a companion who is careful and skilled.”

Talking about this field’s potential, Phúc said there is a high demand in the country: “Although we have only done some basic marketing ourselves, we are always overloaded. I trust more and more people with limb loss will find these products. Because as living standards get higher, more people will need products that can bring mental and emotional values.”

About their vision, Hiệp shared: “Although there is a lot of potential, I think this is not something you can get rich from…Because the handmade process takes a lot of time and energy. I think there will be chances for collaboration in the far future, but for now, due to a lack of workers and materials, Phúc and I will just maintain the production scale as-is.”

To find out more about Phúc and Hiệp’s work, visit their Facebook page.

[Photos courtesy of Phúc and Hiệp]