This is an excerpt from Chapter 2 of the book Pills, Teas, and Songs: Stories of Medicine Around the World by Debby Nguyen, republished with permission. Debby's family of pharmacists and doctors practices both traditional and western forms of medicine.

The week before I left Saigon in August 2019 for college in Boston, it felt like I was packing my entire existence into two pieces of luggage: clothes, my favorite books, stationery, postcards and letters I had collected over the years and, of course, medicine.

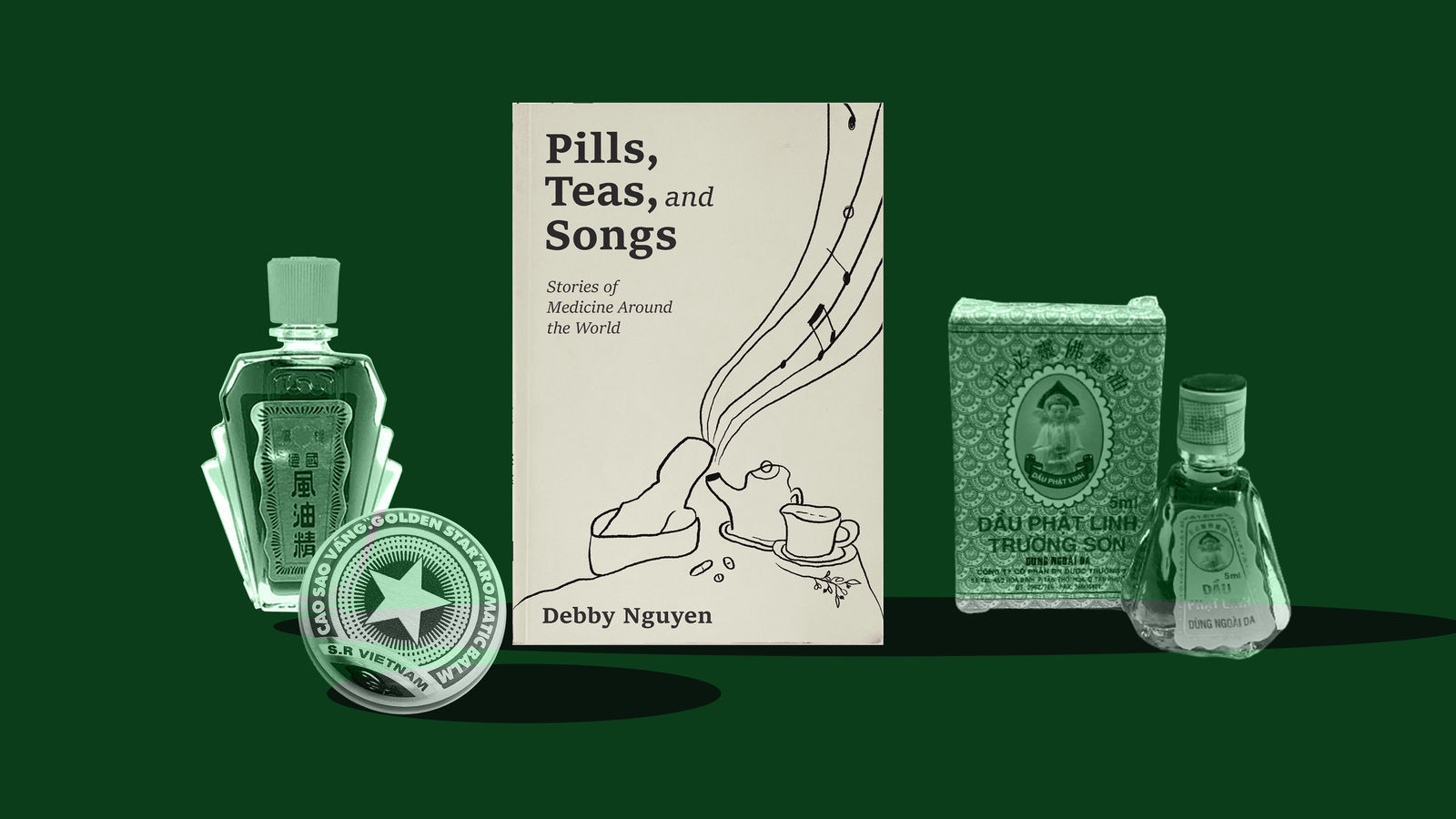

“Bring these with you, over there they won’t have this and even then it’s going to be so much more expensive!” My dad said as he stuffed a small cloth bag with medicine in blister packs: translucent green soft-gels that work wonders for colds, orange-flavored cough drops that taste just like candy for my frequent sore throats, and a thumb-sized bottle of dầu Phật Linh Trường Sơn, a medicated oil that smells so strong your nose stings. “It’s so cold in Boston, who knows how often you will get sick. If you get a cold, or even a stomachache, rub this oil on it and it will warm you up.”

The first few months in Boston, I forgot about the bag of medicine completely, but as soon as the temperatures dropped and winter hit in full force, I found myself digging for it from the bottom of my dresser. I ended up burning through the supply of cough drops, and on cold nights, I would rub dầu Phật Linh Trường Sơn on the soles of my feet, which made it easier to sleep. The smell is unique and hard to describe — spicy, sweet, herbal, and incense-like, which is not surprising considering the oil’s ingredients: peppermint oil, menthol, clove oil, eucalyptol, and camphor. If I had used the oil back in Saigon, I would not have given it a second thought, not even to the strong, refreshing smell. However, in Boston, this tiny bottle is a little piece of home, a reminder that my family is with me wherever I go. Surprisingly, I’ve also found dầu Phật Linh Trường Sơn on Amazon and other online stores for Vietnamese products, which cater to the Vietnamese population in the US.

"Are you going to write about dầu xanh?" asked a Vietnamese-American connection I made on LinkedIn when I told her about my book. "Of course, I grew up with it. Didn’t we all?"

The famed dầu Phật Linh Trường Sơn.

Having grown up with versions of the oil at home, it’s always been a household essential that I never looked too much into. However, now that I’m thousands of miles from home and rarely talk to another Vietnamese person, it’s amazing that this is something I could connect with a stranger over because of our shared heritage. I wanted to dig deeper into what this fragrant medicated oil really is and why it’s become so popular with Vietnamese people everywhere.

Dầu Phật Linh Trường Sơn has long been used in traditional Vietnamese medicine, and the name translates to “Oil of the Buddha in Truong Son,” which refers to the Truong Son mountains in central Vietnam, where the manufacturer is based. The connection between a medicated oil and the Buddha seems far-fetched, but considering Buddhism’s long history in Vietnam and the religion’s wide influence in daily Vietnamese life, it becomes understandable.

Vietnamese Buddhism, strongly influenced by Chinese Buddhism and belonging to the Mahayana stream, emphasizes self-discipline and proper conduct in everyday life. Vietnamese Buddhist leaders are also incredibly influential outside of Vietnam, especially in the United States. Thích Nhất Hạnh wrote more than 100 books, including The Miracle of Mindfulness, and famously taught that we could all be enlightened by finding happiness in the simple things. Although the majority of Vietnam’s population officially identifies as non-religious, Buddhism is applied often as a life philosophy instead of a religion, in combination with folk traditions and ancestor worship. For example, my family visits Buddhist pagodas every Lunar New Year, has altars for our ancestors at home, and our “oh my God” (trời ơi) refers to the God of the Sky.

Other common names for the oil are dầu xanh (green oil) and dầu gió (wind oil). While “green oil” makes intuitive sense because the packaging is usually green and there is a variation of this oil that is green in color, I’ve never thought about the meaning behind calling it “wind oil.” In Vietnamese culture, there is an ancient belief that when you get an unexplained sickness with symptoms like headache, watery eyes, and a slight fever, you’ve been hit with “bad wind.” In traditional Chinese medicine as discussed in the previous chapter, wind is considered one of the Six Evils that cause illnesses, and in traditional Vietnamese medicine this is also a commonly accepted concept and has become part of the language people use to describe cold-like symptoms and subsequently medicine products to treat them.

Nguyen and her family at their pharmacy in Hanoi.

In a blog post for Vietnam Talking Point, guest blogger Ben Khuc reminisces about growing up with the Eagle Brand Medicated Oil, a popular “green oil” brand among the Vietnamese diaspora:

“This elixir has been hailed as the Asian panacea to all the diseases in the book. Got a cut? Rub this on it. Got muscle pain? Rub this on it. Have a cold? Rub this on it and scrape your skin with a soup spoon (if you don’t know what this procedure is, you’re better off not knowing).”

The “soup spoon” procedure Khuc mentioned is called cạo gió, which literally means “scrape the wind,” where you rub a coin or a spoon on to the skin. Cạo gió creates purple bruises that run down a person’s neck and back, and to somebody who is unaware of the procedure, they either look like the result of torture or the worst love bites. Cạo gió is a persistent part of Vietnamese medicine and is believed to help release “toxic wind” in the body and restore balance.

Now that I think about all the Vietnamese traditions and products that have “wind” in its name — dầu gió (wind oil) and tránh gió (to avoid bad wind) — it’s fascinating to realize how our culture places so much weight on “bad wind” as an external factor that causes illness. In fact, “wind syndromes” are now included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, as a key culture-bound concept of distress. For example, Vietnamese (and Cambodian) refugees with post-traumatic stress frequently interpreted somatic-type anxiety as disorders of “wind."

Chinese medicine has certainly influenced Vietnamese medicine, evident in the belief of wind as one of the bad excesses, and as seen on dầu Phật Linh Trường Sơn’s packaging with Chinese characters on all sides. In addition, the packaging design also has elements seen on heritage Chinese medicine packaging: the prominent use of portraiture — in this case, the Buddha — to inspire credibility in a majority-Buddhist Vietnam, repeated background pattern with the manufacturer’s logo, and use of auspicious colors such as yellow, red, and green.

Dầu Phật Linh Trường Sơn contains peppermint oil, menthol, clove oil, eucalyptus oil, and camphor and is indicated for colds, cough, motion sickness, abdominal pain, to mosquito bites, sprains, and arthritis. While Dầu Phật Linh Trường Sơn is popular among Vietnamese families in Vietnam, the Vietnamese diaspora, especially in the US, loves the Eagle Brand Medicated Oil. It was created in 1935 by a German chemist, Wilhelm Hauffman, for a Chinese merchant named Tan Jim Lay, who owned the J.Lea & Co. trading house in Singapore. Hauffman was perfecting the extraction of chlorophyll at the time, which gave the oil its iconic green color.

In the 1960s, Eagle Brand Medicated Oil was first introduced to Vietnam, and it’s grown in popularity since then. According to Eagle Brand, they planned to invest in manufacturing the "green oil" in Vietnam in the 1970s, but the plan didn’t go through due to the outbreak of the American War. After the war, demand continued to persist in areas where Vietnamese immigrants settled, including the US, Canada, Europe and Australia.

While both Eagle Brand and dầu Phật Linh Trường Sơn contain the same ingredients, the Eagle Brand oil is distinctly green — from the packaging to the bottle, the cap, and the oil inside. Its Art Deco-inspired packaging design and bright green hue is a familiar sight to not only those who grew up in Vietnamese households, but also former Soviet countries. Victoria Frolova, a professional perfumer writes in her blog Bois de Jasmin: “During my childhood in Ukraine, medicated oils and Cao Sao Vàng (Golden Star Balm) were considered as nothing short of panacea.”

Based on my mom’s memories of growing up in the post-war era, when products, people, and ideas were frequently exchanged between Vietnam and the Soviet Union, Cao Sao Vàng gaining cult status in Ukraine is a story I can’t wait to tell her about.

Another interesting observation I've made is how Vietnamese Americans find comfort in shopping for "Vietnamese green oil," on Amazon or Asian supermarkets and stores, e-commerce shops in Vietnam do the opposite and often advertise the Eagle Brand Medicated Oil as “bought in the USA” or “original - bought from Singapore.” This is because in the past when people traveled abroad, they often bought bottles of Eagle Brand oil as gifts for family and friends as a souvenir since there are many copycat brands; if sellers said they bought the oil from the US or Singapore, customers would think it's the "legit" Eagle Brand.

In my opinion, the difference between how the two groups perceive authenticity is mainly based on the diaspora's desire to be connected to Vietnamese identity while homeland Vietnamese view imported products as a form of status, as they are often more expensive than local goods. Although only a theory, I see it even in how I get excited about buying the simplest Vietnamese treats in Boston (sticky rice!), while my mom insists on hoarding Ferrero Rocher chocolate at the airport whenever she travels abroad .

I grew up in Vietnam’s two largest cities — Hanoi and Saigon — surrounded by medicine of all forms. At home, my parents always stocked up on common household medicines like dầu Phật Linh Trường Sơn. When I was little, they used to take me to my grandparents’ house in Hà Tây, just outside of Hanoi, where dad grew up and where my grandpa practiced traditional medicine or thuốc đông y (Eastern medicine).

Debby Nguyen (in pink) with her family.

When I started primary school, my parents opened their own independent pharmacy on the first floor of our three-story house in Hanoi. I spent most days after school behind the clear display cabinets filled with medicines that most people are more familiar with, cough drops, acetaminophen, antibiotics, in blister packs and sterile containers. I used to look forward to weekends at my grandparents’ house, where I could play with my older cousins and help my grandpa count and package his powders and pills into bags, which we put into bamboo baskets that stacked to the ceiling.

After my grandpa passed away, patients stopped coming to the house and my visits became less frequent. I never thought much about the medicine that my grandpa practiced, the only time it ever comes up in our family is when my dad reminisces his childhood on long car rides, and he would talk about going to the mountains as a kid to help my grandpa pick the right ingredients for his medicine.

I mostly stayed quiet when my dad talked about my grandpa and thuốc đông y, mostly because I didn’t know enough to contribute to the conversation and because there’s dissonance in how my family talks about medicine versus how we practice medicine. I mentioned this sense of dissonance to my mentor in a recent conversation on medical anthropology, and she mentioned having a similar experience growing up in a Pakistani immigrant family: “Yes, I feel the same way. My dad’s a physician but at home when I get sick, going to the hospital was not an option; instead, my mom would make this hot drink with ginger, turmeric, and cardamom. What our parents do and what they say about medicine are very different from what they actually practice in their home.”

I grew up behind cabinets of western medicine, my parents studied western medicine in Pharmacy school, and I’m now a Pharmacy major at Northeastern University, which means western medicine has been the primary lens through which I view healthcare. However, despite my grandpa’s successful career in traditional Vietnamese medicine, the curious way my dad talked about his amazement by my grandpa’s knowledge in medicine, and the way I’ve always accepted the existence of medicated oil used to “scrape wind,” I had not looked deeper into Vietnamese medicine or tried to understand it more until now.

Although the origin of thuốc Nam, Traditional Vietnamese Medicine or literally "southern medicine," is not clear, most scholars agree the field began evolving about 2,200–2,500 years ago. According to the book of Traditional Pharmacology published by Vietnam’s Health Ministry, following the Chinese occupation of the Red River Delta, which included Hà Tây, thuốc Nam developed along side Traditional Chinese Medicine — in Vietnamese: thuốc Bắc, literally "northern medicine." After over a thousand years of Chinese rule, Vietnam gained independence in 938 CE, and Vietnamese medicine developed significantly in the next 1,000 years.

It’s commonly accepted that the founder of Vietnamese Medicine was Tue Tinh, a Buddhist monk born in the 14th century who is considered the god of Vietnamese herbs. Tue Tinh wrote highly important medical books, including Great Morality in the Art of Medicine. Another one of the most important and revered physicians in Vietnamese medicine is Hai Thuong Lan Ong, who in the mid 1700s published a 66-volume Encyclopedia of Traditional Vietnamese Medicine that is still referred today as a fundamental book of the field. He famously said, "Nam dược trị Nam nhân," meaning "Vietnamese people are treated by Vietnamese medicine."

After a millennium under Chinese rule, Vietnamese doctors like Hai Thuong Lan Ong inspired pride for Vietnamese medicine in Vietnamese people. Indeed, while Chinese medicine and Vietnamese medicine are highly interconnected and have many similarities, especially in the intergenerational underlying beliefs of yin-yang and the elements, there are also differences. Unlike Traditional Chinese medicine which calls for a consuming brewing process, thuốc Nam involves different combinations of herbs that are simply chopped or grounded to be consumed.

“Our family made both thuốc Bắc and thuốc Nam! Your grandpa usually used Vietnamese medicine to treat patients, but your great-grandfather often used Chinese medicine. Your great-great-grandpa also practiced medicine, did you know that?” my dad said when I texted him to ask if my grandpa mainly followed Chinese or Vietnamese medicine, because both are under the umbrella of eastern medicine. I was surprised to hear that my great-great-grandpa was also a traditional medicine practitioner — it means I’m the fifth generation in my family to study pharmacy or medicine.

My dad’s always been the most passionate person in our family when it comes to healthcare and growing up I never fully understood why it’s the only topic he ever talks about with true excitement. After the initial surprise, it made me really proud to be studying pharmacy. More than just a career, the field is a family legacy of keeping people healthy that I now carry for the rest of my life.

An example of Vietnamese medicine remedies that remain today include using garlic to cure spells of fainting, using water morning glory (Ipomoea aquatica) to cool and restore balance in the body, and chewing betel (nhai trầu) to prevent tooth decay. When my grandparents were alive, they both chewed betel and as a child I was always a little scared to ask about it because I didn't see my other grandparents (on my mom’s side) do the same, and my grandma had a huge spit jar for after she had finished chewing the leaves.

She also had teeth that were dyed shiny black like lacquer, a practice that is now almost obsolete but used to be a rite-of-passage for coming-of-age Vietnamese women. It's believed that black teeth protected their owners from evil spirits, as long white teeth were associated with ghosts. I always thought the betel chewing made her teeth black, but as I've grown older I realized they are separate customs.

The custom of betel chewing is commonly practiced in northern provinces, like Hà Tây where my dad's family is from, and this tradition is an important cultural activity in Vietnam. Betel leaves are folded in different ways and some calcium hydroxide is usually dabbed inside, then slices of dry Areca nuts (betel nuts), which are seeds of the Areca palm's fruit, are placed on the upper left and tender Areca nuts on the upper right. In traditional medicine, chewing betel leaf with Areca nuts is a good remedy for bad breath, and when chewed the euphoric stimulant effect produced by the nut's active ingredient, arecoline, can be felt for several hours. Although betel chewing is no longer as common as it used to be even one or two decades ago, in Vietnam, the Areca nut and betel leaf are important cultural symbols of love and marriage. It's often said that betel chewing starts the conversation between the two families about a young couple's marriage, and thus the leaves and nuts are used ceremonially in Vietnamese weddings to illustrate the idealized marriage that would be as inseparable as the combination of the Areca nut and betel leaf.

Today, in industrializing modern-day Vietnam, traditional Vietnamese medicine is very much alive, with renewed interest even among young people. In big cities like Hanoi and Saigon, traditional medicine is used to supplement western medicine; there are also hospitals in most cities dedicated to the practice, such as the Hospital of Traditional Medicine in Saigon. Numerous herbal medicine stores selling ingredients for Vietnamese medicine can be found in Saigon, and the FITO Museum in the city center showcases the evolution of traditional Vietnamese medicine including nearly 3,000 artifacts from the Stone Age.

According to Nguyễn Thanh Hằng, FITO Museum’s manager, “The goal of the museum’s founder (Dr. Lê Khắc Tâm) is to preserve traditional cultural values of our forefathers...in hope that the next generations know about the development and growth of traditional Vietnamese medicine.”

I believe this resurgence is happening because unlike previous generations, which focused on survival during wars and colonization, young people enjoy a relatively stable economy that makes space for exploring and developing what it means to be Vietnamese. Even if they don’t directly use traditional medicine, I think there’s an increased desire to know more about Vietnamese culture and history among people my age. Even for the Vietnamese diaspora, a study by the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine in 2016 found that the Vietnamese people who have lived longer in the United States are more likely to use TVM, which is surprising given there are perceptions that only recent immigrants use traditional methods due to cultural barriers. Researchers propose this could be because “The more acculturated Vietnamese are the more they may want to connect to their heritage...or having more expendable income and not having to rely on the free care for conditions that cannot be satisfactorily addressed by Western cures.”

My most recent conversation with my dad was about hoàn ngọc trắng (Pseuderanthemum palatiferum), a popular medicinal plant among the Thai and Vietnamese people that does not yet have a common English name. A few days prior, I spoke to a monk in Thailand who was originally from Boston who was curious about the plant after hearing a folktale from his teacher: “He said during the Vietnam war, Americans who were lost or stranded by the jungle survived by eating it.”

Without much knowledge, I messaged my dad for help.

“This plant is for tooth pain and other digestive problems when you chew it. Hoàn ngọc trắng has great antibacterial properties and my grandpa used to use it. About seven years ago, there was a craze in Vietnam too and people started using it again,” he messaged me within a couple of minutes, at 7am on a Sunday.

Once again, I’m surprised by how much he knows. Reflecting on my own journey in learning about the story of traditional Vietnamese medicine, I now feel not only pride in Vietnamese cultural persistence, but also a desire to continue learning as much as I can to one day tell the next generations what I know.

This excerpt has been edited for length and style. Pills, Teas, and Songs: Stories of Medicine Around the World is available for pre-order here.