From the very first discussions in 1868 regarding a new marketplace for Saigon, it was not until 1914, that Bến Thành Market became a reality. The birth of the market was like a dream come true, one that came together after nearly five decades of debate in search of solutions for the city’s infrastructure woes.

The five-decade quest to seek a “worthy” marketplace

In her research conducted on the vendors of Bến Thành, anthropologist Ann Marie Leshkowich recounts the lengthy discussions of then Saigon’s colonial administration regarding the establishment of a new commercial center, one that, according to them, must become a place “worthy” of the metropolis they were helping to create.

In 1868, the French had only spent about one decade trying to install a colonial network in Vietnam. Members of the Municipal Council (Conseil Municipal) had the thought of building a new marketplace from metal, replacing traditional thatch markets. In 1869, a budget of 110.000 francs was greenlit, but by 1870, the estimated expenditure had ballooned threefold, causing them to reconsider the planned building methods and amount of materials.

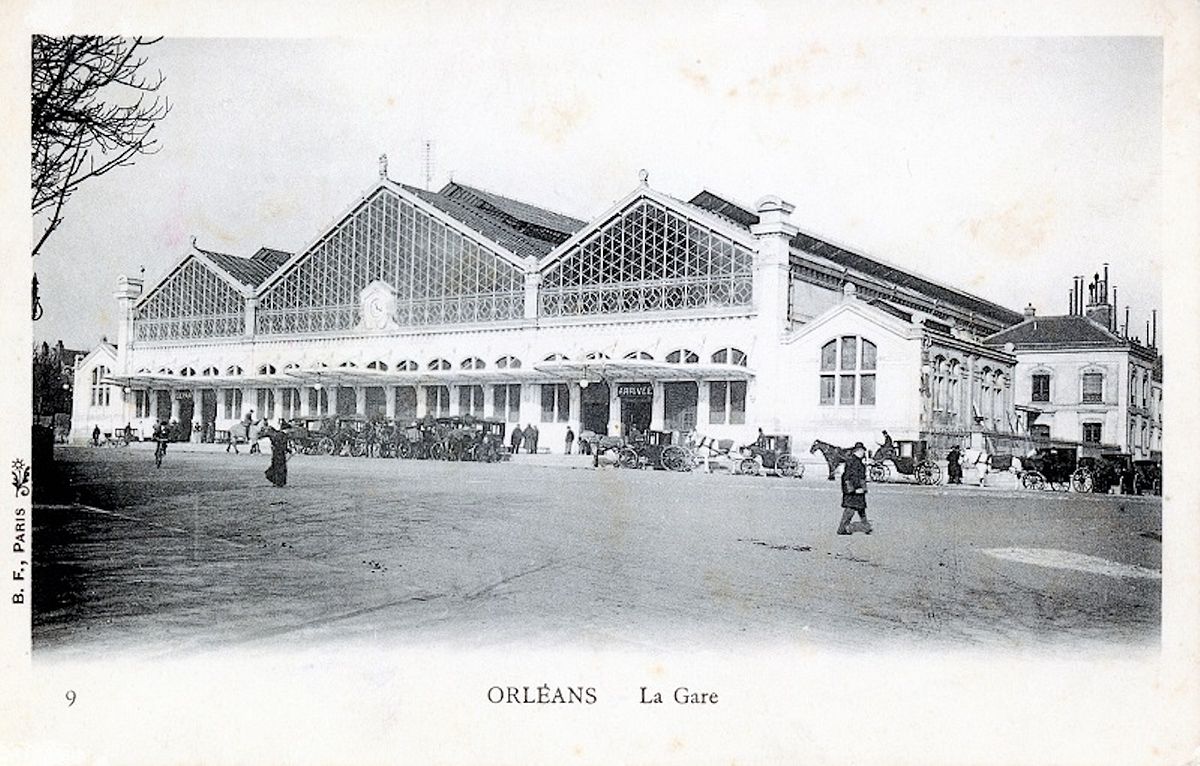

The Gare d'Orléans in France was used as a reference for the design of Bến Thành. Photo via Flickr user manhhai.

A few members of the council offered up the metallic structure of the Orléans Train Station as a possible design for the market’s carapace. At the time, a lightweight iron frame was a cost-effective choice as it would allow for fast installation, and make way for a wider interior compared to previous techniques in columns and load-breaking walls. Over time, this metallic frame would be utilized prevalently in bridges and other public landmarks like the Saigon Central Post Office. Still, when it was first suggested, the use of metal was a matter of debate.

In the same year of 1870, chợ cũ (old market) — which was then based along the Chợ Vải Canal, now Nguyễn Huệ Boulevard — was destroyed by a fire. The accident made the council realize that a thatched roof would be a risky choice for the new market. Back then, houses with a bamboo or wooden skeleton and a thatched roof were quite popular, so officials had to find ways to transition neighborhoods to brick walls to increase both safety and aesthetics. Hygiene was also a critical topic of discussion as traditional markets, often built right on the bare ground, were deemed unhygienic. As a result, council members agreed that the new market would feature a stone floor and proper plumbing for washing every evening.

A new structure of wood, roof tiles and stone floor was built in 1872 to replace the one that burned down in 1870. The photo shows the old market on Charner Boulevard, now Nguyễn Huệ. Photo via Flickr user manhhai.

The new marketplace was constructed in mid-1872 by contractor Albert Mayer, featuring elements of wood, roof tiles and a granite floor. It helped to quell the city’s immediate need for a trading center, even though it was rather modest in scale compared to how the committee members envisioned a commercial hub “worthy” of Saigon. Subsequent efforts to expand the city’s infrastructure were paused as the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) caused investments to dry up. Many other crucial amenities like the Central Post Office were also put on the back burner in the 1870s and 1880s.

In 1893, over two decades after the Franco-Prussian War, plans to build public infrastructures started to reappear in council sessions. To revamp the city’s appearance, the mayor proposed building three new structures: an opera house, a city hall, and a central market. The Saigon Opera House was finished seven years later while the Hôtel de Ville (City Hall) was completed in 1908. The central market, however, continued to exist only on paper due to much debate.

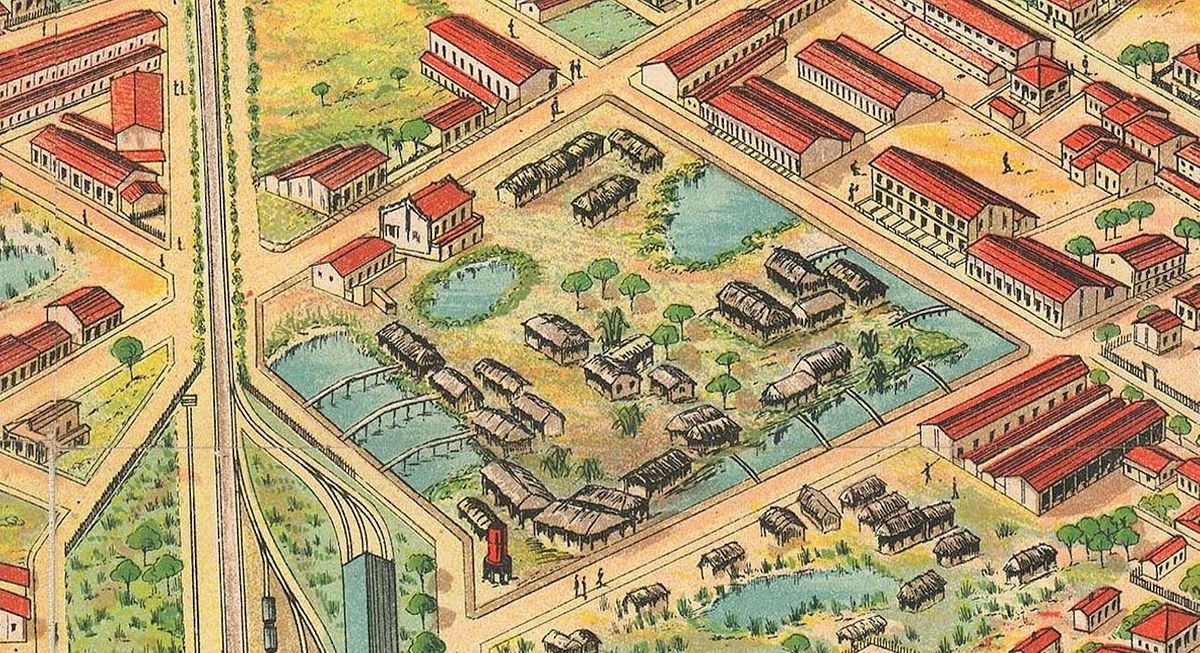

The Bồ Rệt Swamp in an illustrated map by Gaston Pusch (1898). It depicts the landscape contrast between the brick-walled, red-roofed houses and thatched shacks. Image via Flickr manhhai.

The building site for the new marketplace was decided to be in the vicinity of the Bồ Rệt Swamp (Marais Boresse), an expansive stretch of swampy land right in the heart of the town, where Saigon’s poorest lived in makeshift huts erected on the wetlands.

This area was once very well-connected with the Saigon River by many rivers and streams, with dependable daily tides regulating household waste and keeping the vicinity relatively clean. However, real estate developments from the middle of the 19th century until the 1890s rendered local waterways clogged. The swamp used to link with the Saigon River via the Cầu Sấu Canal, but in 1867–1868, this too was filled in to make Canton Street (now Hàm Nghi Boulevard). Inevitably, the remaining swamp land became a still-water breeding ground for mosquitoes and sickness.

In the eyes of colonial urban planners, Boresse was one of the savage challenges “threatening and infringing on the civilization” that they labored over. Turning this lost world into a commercial center would help improve local beauty and quality of life in the city, and placing the marketplace here would make more sense than the Nguyễn Huệ area (of today Saigon), which was getting cramped.

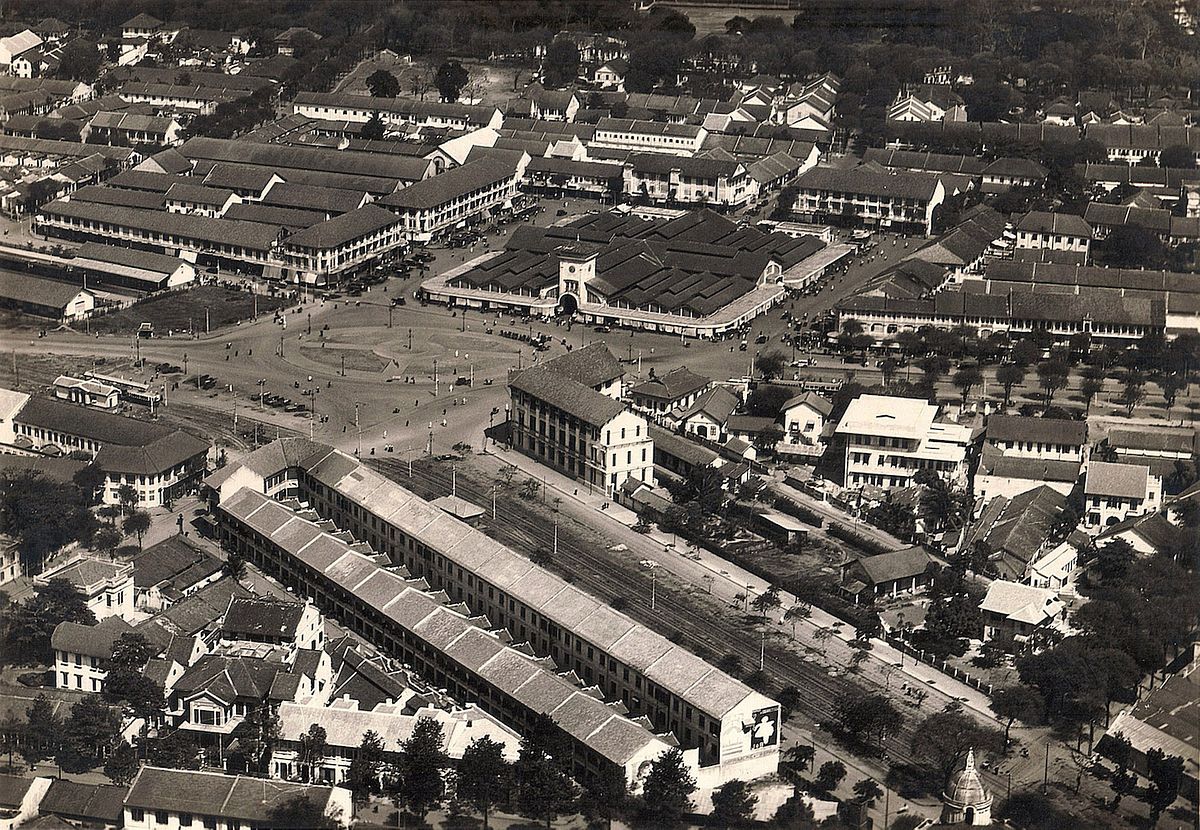

After decades of planning, the Bồ Rệt Swamp was transformed into the central market, with rows of shophouses surrounding it. Image by Léon Ropion, circa 1920, part of the C Neykov collection. Image via Flickr user manhhai.

In 1893, the council officially approved the plan to construct a new marketplace at an estimated cost of 400,000 francs. Budgetary debates continued to bog down the market’s building progress, as did the fact that the opera house and city hall were favored by the council. It wasn’t until 1907 that the council started to reassess the market construction plan, but the costs once again skyrocketed. In 1908, the building plan was approved for the second time amid rising construction fees.

Finally, the central market was completed in 1914. The opening event, taking place from March 28 to 30, garnered special interest from the then media. The city organized a slew of festivities, including public performances like lion dance, circus shows, and fireworks, attracting crowds of Saigoneers in attendance. Lục Tỉnh Nhân Văn, a Saigon-based newspaper, chronicles the thoughts of vendors who just moved into the new market building; many expressed the joy of doing business in a spacious, well-ventilated, and clean place.

Utility and aesthetics

Bến Thành Market in 1914, when it was opened for the first time. Photo via Tuổi Trẻ.

Bến Thành overwhelmed Saigon inhabitants at the time thanks to the interior’s sizable attic and an eye-catching clock tower. Compared to other prominent public buildings from the end of the 19th century to the early 20th century, Bến Thành Market’s decoration was noticeably restrained.

In many planning sessions by the City Council, the market’s aesthetic appeal wasn’t as highly prioritized as hygienic and health concerns, so the design only focused on tackling necessary utility cornerstones like having high and spacious ceilings to aid ventilation, and features like a stone floor and a drainage system. If the opera house and city hall were adorned with intricate, iconic reliefs, the marketplace hardly received any attention in beautification.

An image from the 1960s shows some decorations made of ceramic and louvers were added to the front of the market. Photo via Flickr manhhai.

In 1952, ceramic reliefs were installed above the market’s four entrances: North, South, East and West. According to the essay ‘Tìm lại tác giả phù điêu chợ Bến Thành’ (Finding the author of Bến Thành Market’s reliefs) by Nguyễn Minh Anh, these artworks were designed by Lê Văn Mậu (1917–2003) and created by artisans of the Biên Hòa Artisan Cooperative, both commissioned by Bến Thành Market.

The reliefs feature some flora and fauna species that represent the market’s produce; they make use of the distinctive color palette of Biên Hòa Ceramics: white and copper blue. Each work, comprising many small ceramic fragments, was baked in Biên Hòa and assembled at the market. Besides the reliefs, the arches and ventilation blocks were also later additions, bringing a linear design that detracts from the original version of Bến Thành built in 1914.

The series of ceramic reliefs embellishing the gates of Bến Thành. Photos by Nguyễn Lương Cao Nhân.

From modern to traditional

In her research, Leshkowich remarks on the shift in perception among Saigon residents about the market. Initially, colonial council members envisioned it to be a cutting-edge, modern, and civilized commercial hub following European standards.

Over the years, the cutting-edge vision slowly became replaced by the distinctively Vietnamese way of market-keeping by local vendors. Bến Thành Market, from a supposed beacon of European civilization, had a shift in meaning: it has turned into an anchor for memories, one that many Saigoneers living far from home continue to look back on as an architectural icon and a representative for local culture.

From a French landmark, Bến Thành has become a symbol of Saigon folk culture. Photo by Nick Dewolf (1973).

This transformation helps inform how we understand Saigon’s colonial remnants; perhaps they are not all foreign constructions that colonial oppressors imposed on the oppressed. In time, with the help of constant interactions by generations of residents, these colonial-time buildings have indeed been interwoven into local culture, turning into a part of city life and collective memory.

Bến Thành Market belongs to a wide-spanning class of architectural heritage whose values need to be appreciated as a whole. They are the rows of shophouses surrounding the market and along Lê Lợi Boulevard — the signposts of commercial architecture in Saigon across historical eras. At the same time, they can’t be separated from the commercial activities and lifestyles of local Saigoneers. The conservation of Bến Thành is only holistic when considered in the context of an ecosystem of architecture, history, and the modern people.

Bến Thành Market today. Photo by Nguyễn Lương Cao Nhân.

This article was published as part of a content collaboration between Saigoneer and Architecture Excursions (Tản Mạn Kiến Trúc), an independent collective focused on Vietnam’s urban heritage, especially of southern Vietnam. To find out more about Tản Mạn Kiến Trúc’s work, visit their Facebook page here.