It’s been hidden right there in the heart of Saigon for over half a decade.

On one end, neverending, city-wide construction is muffled and ironically forgotten thanks to a veil of sử quân tử flowers concealing its outdoor patio.

On the other end, there’s an open door, one flight of stairs up from an unmarked parking garage guarded by an elderly man, who was confused as to why I woke him from his late morning slumber.

The autograph-covered door into the studio.

“I’m here for Richie,” I say.

“Ahh, Richie, OK, OK,” he nods, reluctantly, motioning me to park outside on the sidewalk.

It’s here on the corner of Pasteur Street and Lý Tự Trọng where one will discover the art studio, speakeasy, and playground known as The Studio Saigon.

It’s also here where one will find Richie Fawcett, sitting on his uncomfortable-by-design DJ equipment box, hunched over his drafting board with black fingerless gloves and a scalpel, tending to his latest rendition of Saigon’s ephemeral skyline. I appear in the doorway, and he stands up immediately to greet me with a smile and a handshake.

Richie Fawcett has spent the last decade creating artworks of Saigon.

I’ve arranged the meeting to talk to Fawcett about his latest book: HCMC Decacity Project, a decade-long art project capturing the changing face of Hồ Chí Minh City from 2013 to 2023.

Archiving history via city sketches

To understand what this book is all about, first, realize that Fawcett is now on his fourth life. Life #1: Student of Egyptian Archaeology specializing in underwater ancient shipwreck photography at UCL. Life #2: Photographer of underground techno night clubs in London and videographer of extreme sports on cruise ships around the world. Life #3: Bartender under former James Bond, Sir Roger Moore KBE in London, and alongside celebrity chef Tony Singh in Edinburgh. Later in 2011, after a year-long stint in Hong Kong, Fawcett traveled south from one Pearl of the Orient to another: Saigon. He had originally only planned to scale up the city’s bar and restaurant scene. Yet, as fate would have it, it was here where his fourth life began.

Remnants of Life #3 live in the space amongst Vietnamese knick-knacks.

Back in The Studio Saigon, the 50-year-old artist from Norfolk, UK is seated to my right on one of his two brown leather sofas in the back bar area, with his latest book open on his lap. Although the book progresses chronologically, our conversation does not.

This book begins and ends in the same spot with the scene that inspired him over a decade ago to start drawing in Vietnam: the view from the top floor window of the Fine Arts Museum across the Quách Thị Trang Roundabout facing Bến Thành Market. Back in 2012–2013 or “the early days” as Fawcett titles them in the book, he starts with a trio of sketches of the Notre Dame Cathedral using pencil on A5 paper — beginning in a similar fashion as his grandfather did using charcoal as a self-taught artist back in the 1930s.

In his studio, Richie shares the story of how this all started.

Call it clairvoyance, a sixth sense, insider information, or just a stroke of luck — he foresaw demolition and felt inspiration. Envisioning the river of time flooding Saigon, Fawcett dove right into the bottom only to resurface a decade later to share his findings. The 150 pages in between recurring plot points feature original drawings of streetscapes, cityscapes, local characters, and panoramic views all captured in the last ten years.

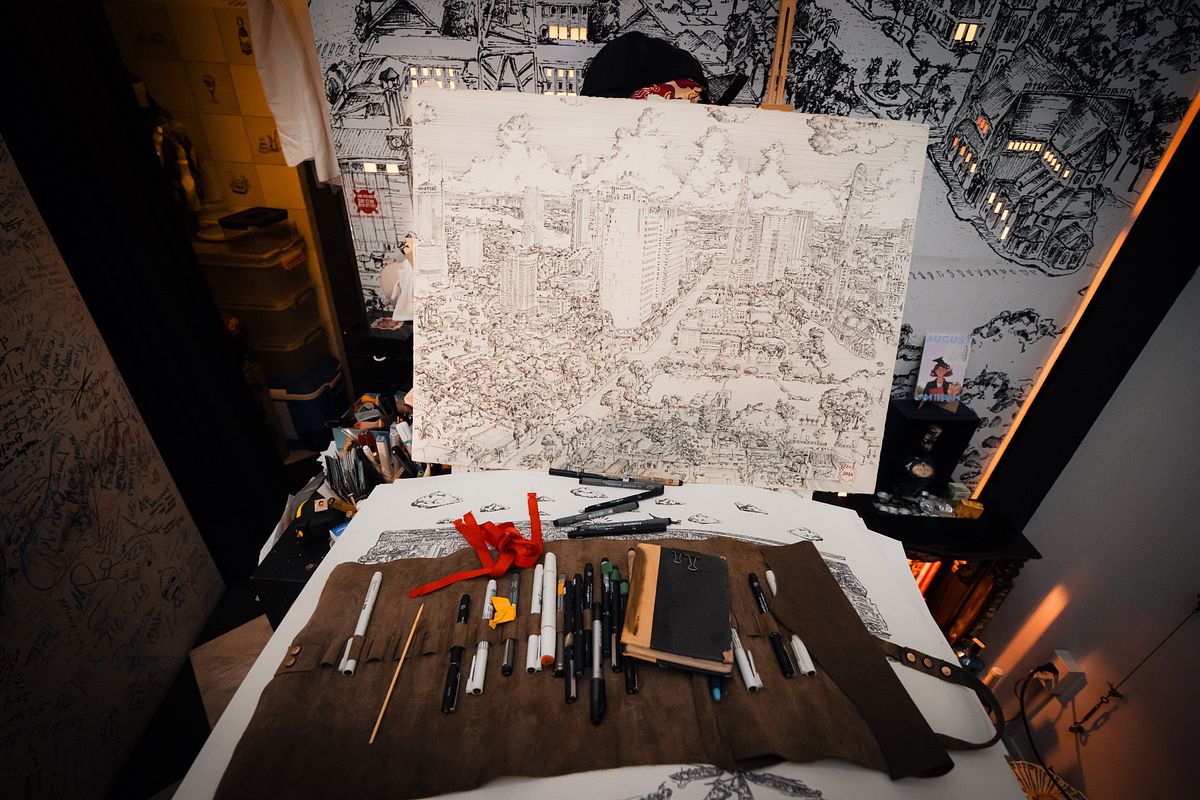

Pens and papers — an artist's best friends.

Paper? French. Hand-made. Daler and Rowney. Aquafine texture. Purchased at a local student art shop.

Ink? Chinese. Preferably watered down from jet black to light grey. Same used by scribes during the Lunar New Year — a period of rejuvenation for Fawcett where the cooler weather clears the city’s sky evoking magical feelings whilst drawing.

Pens? Japanese. Mitsubishi. Somewhere between 0.1 and 0.5. If a pen is wrapped in green tape, it’s fresh. If it’s wrapped in yellow, it ain’t.

Signature stamp at the bottom right corner of all his sketches? Bought by his wife, Duyên, three years in advance. Obsessed with by his son, Harry. “My son loves to stamp everything with different dates,” Fawcett says. The logo — which you can find throughout his studio — symbolizes the shape of the city’s first citadel from back in the 18th century.

Putting the Saigon skyline on the map

It’s almost unheard of that someone prefers to walk everywhere in Saigon, but for Fawcett, the long walks between lunch and dinner services when he used to work as a bar manager years ago became his muse. Repeatedly strolling along the same streets and around the same districts over and over has granted him the ability to notice not only details of new buildings going up into the sky, but also of old faces on the streets.

A snapshot in the story of Saigon.

“The most honest way is to draw something,” Fawcett says. “When you write a diary, words can be left open to interpretation, but drawing a picture, it’s a snapshot and that's why I wanted to draw what I see accurately. It tells a story chronologically in the right order about what really is going on.”

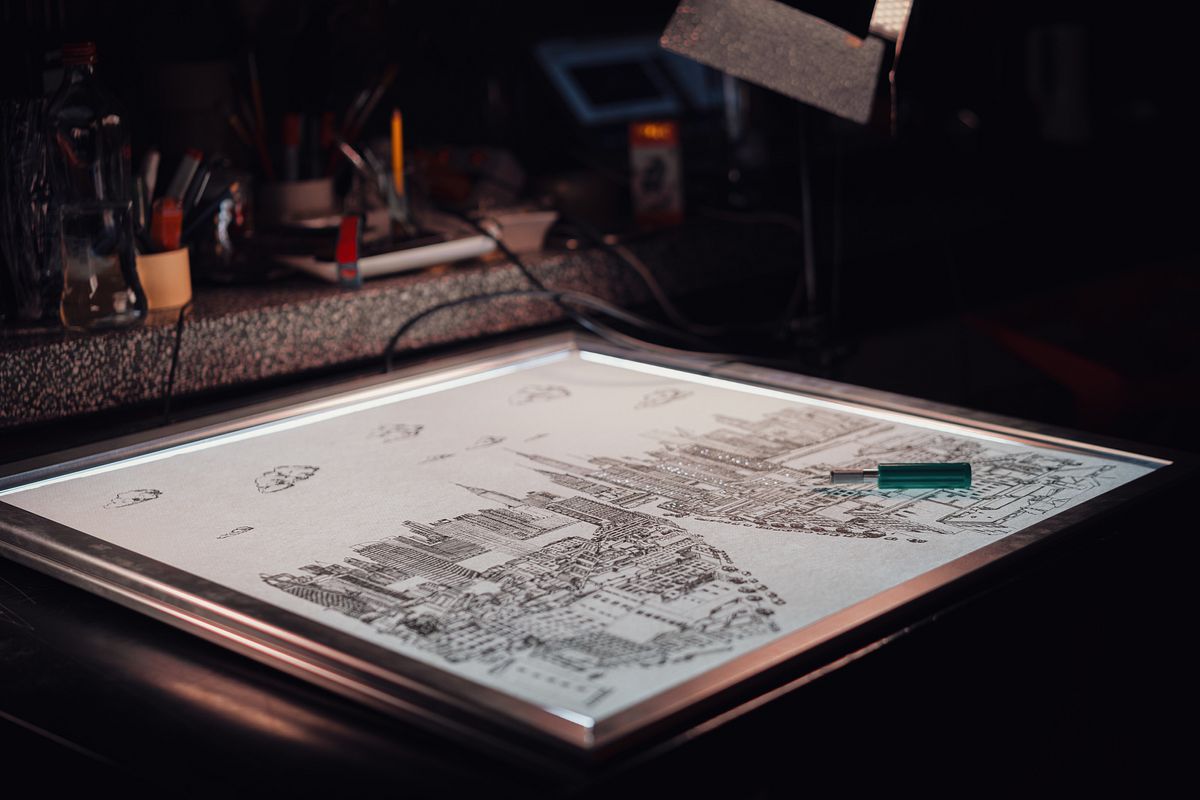

Over time, his drawings went from using only pencil to pencil plus pen. Then, it went to solely pen and soon to smaller and smaller pen tips and bigger and bigger canvases that require 100-plus hours for a single drawing, such as the one in the Brasserie VietNam in New York City or the mural outside of the British Consulate on Lê Duẩn Boulevard. Fawcett tells me that it had 24/7 armed guard for nearly a year. Meanwhile, his largest piece is a five-meter-wide inverted and LED-backlit drawing at Anan Saigon on Tôn Thất Đạm Street. Chef and owner Peter Cuong Franklin has been a close friend and supporter of Fawcett since they met many years ago.

While the artworks in the book are coffee table-appropriate, some of Richie's pieces could span entire walls.

Peter Ryder, the CEO of Indochina Capital, selected Fawcett to be one of the resident artists of Wink Hotels, effectively putting his work on the window shades of every single room in the hotel chain. “It’s a great match, Richie and I, Wink and Richie, because Wink looks to reflect the modern day Vietnam and Richie and his drawings are very much putting on paper his interpretation of Vietnam,” Ryder said.

An appreciation for the little things

When researching the last ten years of Fawcett’s life and work, I kept looking for the turning point in his story. In the process of documenting a decade of “decay and dazzling disorder,” as he writes in the book, when did things flip?

At what inflection point did the trajectory of his life as a self-taught artist change? Was it two years into drawing when he grew confident enough to finally only use a pen instead of a pencil? Or was it the 2015–2016 period, when the volume of his work dramatically increased? Perhaps, it was in 2018, when he quit his salaried job, got married, and committed to being an artist full-time on his terms, resulting in a visible influx in private commissions?

Maybe, it was throughout the 2020–2021 COVID-19 lockdowns when the subject of his work became more experimental and included drawing other cities like London and Santorini, sketching the insides of a tornado, or crafting portraits of his son — something he only does for himself.

Smiling from above.

After meeting Fawcett, visiting his studio, and speaking with others in his circle, I realized I had been looking at this situation wrong all along: HCMC Decacity Project isn’t just a decade-long art project as the title suggests. This is a decade-long anthology, a retrospective collection of love stories pouring out of Fawcett.

It's falling in love with the rooftops of HCMC, where he first saw the full spectrum of its contrasting elements. Falling in love again and again with the Quách Thị Trang Roundabout, even when he saw the statue’s removal taking place on his way home from one night, forcing him to quickly sit down on the curb under the streetlight and capture the moment in real time. Falling in love with his wife Duyên way back when she would pick him up on her motorbike in the early mornings during Tết and take him to Bình Tây Market — a place, as Fawcett writes, if you can’t find what you’re looking for there, “chances are it doesn’t exist.”

A quick sketch of Tết on the street.

And finally, it’s Fawcett falling in love with being a dad where at his studio he has a workbench set up — just like his dad working as a gunsmith when he was a kid — that way his son can now sit right next to his dad and see him first hand create and do what he loves every day.

“That is,” Fawcett says, slowing down and pausing between words, “the exact childhood that I want my son to have.”

Towards tomorrow

Regardless, for him, time ticking away has always been a motivational driver to get out there and make the most of it.

What’s Fawcett up to now? Will there be a fifth life ahead, and what could it entail? Branching out into fashion, launching NFT collections on the blockchain, and marching on his literal artistic race against time to archive the evanescent nature in Saigon? Regardless, for him, time ticking away has always been a motivational driver to get out there and make the most of it. “There’s no time like the present!” he reminds me over WhatsApp.

As Fawcett sits back down on his DJ equipment box with its red citadel logo and “Keep Calm and Make a Sketch” motto etched below and scoots forward to the table nearby an easel with his son’s drawing, he finally shares his overarching philosophy for this book and future plans ahead. It’s simple. “Best plan, no plan,” he says with a smile.

To see Richie Fawcett’s art on display, the official HCMC Decacity Project book launch, “The Art of Art in Saigon,” is taking place on September 29 at 6:30pm at the Wink Saigon Center at 75 Nguyễn Bỉnh Khiêm, D1.