I’ve always loved marveling at the colorful tranh kiếng hung in our altar room whenever I get a chance to visit my mother’s hometown. Since I was little, the paintings have been an indispensable part of my grandparents’ homestead. Tranh kiếng is present everywhere in people’s houses in the town, but I’ve never thought to ask who created unique art pieces that perfectly encapsulate the soul of the southern community.

When did tranh kiếng arrive in southern Vietnam?

I started by asking my grandpa about where he got the paintings, but he couldn’t remember their exact origin, just noting that they used to be really popular, especially during Tết, but they are rarely seen nowadays.

According to historical records, tranh kiếng, known as reverse glass paintings in English, started appearing in the 19th century, brought into Vietnam by Chinese immigrants. At first, the works adorned the walls of The Imperial City in Huế during the reign of Emperor Minh Mạng. Emperor Thiệu Trị, the eldest son of Minh Mạng, commissioned artisans in China to create a set of 20 pieces featuring Huế’s most breathtaking landscapes alongside the emperor’s poetry. This gave rise to the name “Imperial Huế glass painting,” referring to the artworks enjoyed by the royal court and nobles in Huế.

When the 20th century came, tranh kiếng showed up in Chợ Lớn for the first time, marking the beginning of the art form’s decades-long endurance in southern homes. Resettling in the Mekong Delta, some migrant families from Guangdong took glass paintings with them. They were often themed around deity worship, so the people treasured them as a piece of their spiritual heritage. Chợ Lớn-style tranh kiếng, thus, was first widely known as spiritual artworks, though over time, their subject matters expanded to include content espousing fortune, prosperity, and abundance.

A depiction of Guanyin, the Chinese interpretation of Avalokiteśvara, painted by Chinese artisans in 1920. Image via VnExpress.

In the 1920s, painters in Lái Thiêu (Bình Dương) managed to learn tranh kiếng-making techniques from Chinese artisans and began coming up with new designs catering to Vietnam’s local worshipping practice. Thanks to better localization, vibrant color palettes, and the novel incorporation of mother-of-pearl, Lái Thiêu quickly made a name for itself as the southern region’s top-tier producer and distributor.

Over the next decades, as Indochina’s first-ever railway was established in the south, linking Saigon with Mỹ Tho, tranh kiếng hopped on the train and spread across the Mekong Delta. One of the most enduring forms it’s taken in Mỹ Tho since then until now is ancestral worship decorations, which evolved from nine-frame carved and lacquered panels. The panels are often paired with a hoành phi board bearing the family name.

A set of nine-frame panels. Photo via Thanh Niên.

When they got to the Mekong Delta, tranh kiếng once again grew to adapt to the local cultures, resulting in more affordable genres of paintings featuring either landscapes or folk story characters like Thoại Khanh-Châu Tuấn, Lưu Bình-Dương Lễ, Phạm Công-Cúc Hoa, etc. These depictions usually attempted to replicate the illustration styles of artists like Hoàng Lương or Lê Trung, who brought the characters to life with their official artworks. Following this content expansion, tranh kiếng transcended their original purpose as worship art to become purely decorative objects, beautifying empty spaces in the home like dividers and chamber doors. In addition, in regions of the delta with significant Khmer communities, the subject matters of tranh kiếng were heavily influenced by Theravāda Buddhism.

Tranh kiếng as spiritual artworks. Photo via Báo Phụ Nữ.

Over decades of development, two main branches of tranh kiếng emerged — spiritual art and landscape art — catering to both the people’s needs for altar decoration and household decoration. Cultural Studies researcher Huỳnh Thanh Bình explained the rapid rise in popularity of this art form in southern Vietnam: “Southern Vietnam is a land of multiple cultures and ethnicities, so once tranh kiếng arrived here, it satisfied a need to decorate and worship during special occasions, especially ancestral worship art.”

Even though the main material for these paintings, glass, is called “kính” in Vietnamese, the people avoided the correct name but instead opted for an approximated term, “kiếng.” According to writer Lý Đợi, this is due to a long-enduring tradition of Vietnamese paying respect to important figures by avoiding using their names for common usage, or húy kỵ. In this case, Nguyễn Hữu Cảnh was a 17th-century military general who spearheaded the imperial army’s southward expansion efforts, credited with the founding of many townships in the south, including Saigon, and was widely considered a national hero. His birth name was Nguyễn Hữu Kính, so southern Vietnamese, out of respect for him, used alternative words for objects including “kính” and “cảnh.”

Tranh kiếng in the life of southern Vietnamese

Since it was first introduced to Vietnam, tranh kiếng has strongly taken root and flourished throughout southern localities as the people have accepted it as a familiar part of their daily life.

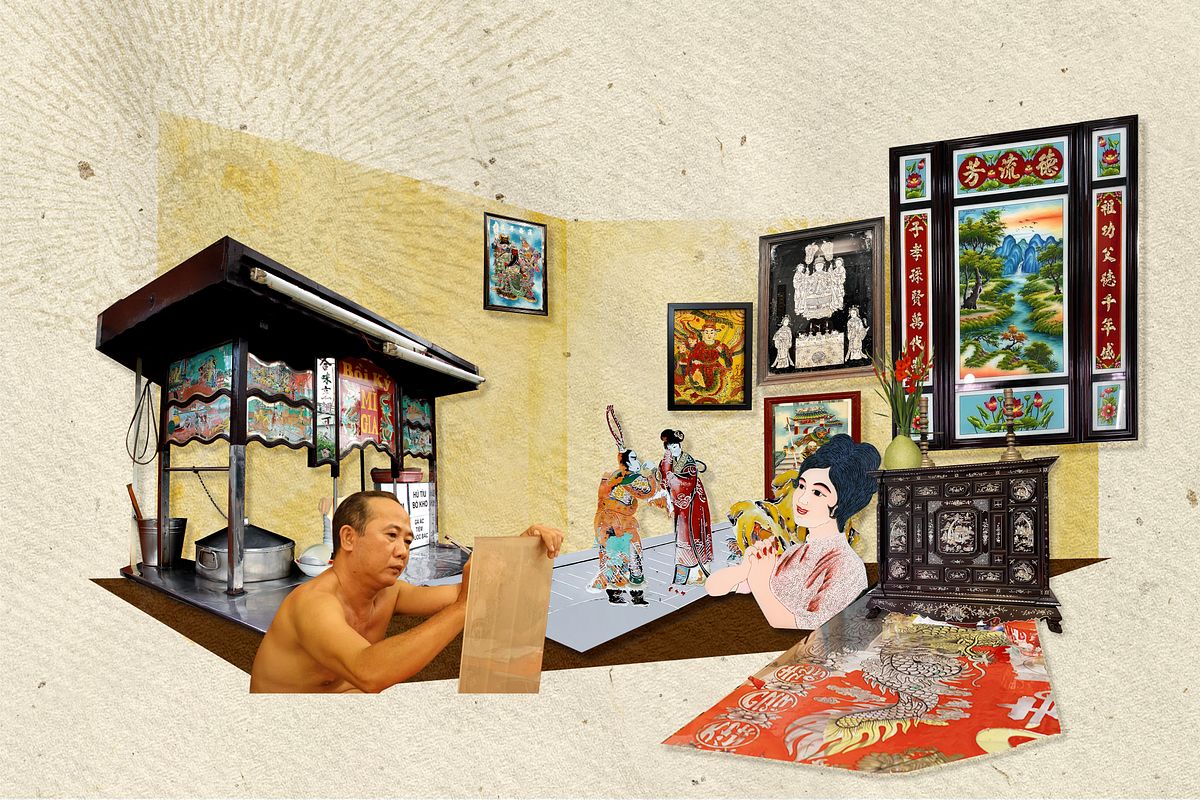

Decorative tranh kiếng works on a hủ tiếu cart run by Hoa Vietnamese vendors in the 1960s. Photo via VnExpress.

Painter and art historian Trang Thanh Hiền said of tranh kiếng’s main genres: “Just like other genres of traditional painting from Đông Hồ, Hàng Trống, Kim Hoàng or Làng Sình, southern Vietnam’s tranh kiếng often has four main themes: spiritual and worship art, ceremonial art, landscape art, and storytelling art. Of the four, the first category is the most widely developed, while the last is the rarest. It’s usually created to adorn wardrobe doors, bed frames, and Chinese-style noodle carts.”

Spiritual tranh kiếng can highlight subjects like Buddhist iconographies, ancestral worship, calligraphy, etc. It’s one of the most commonly seen art styles in temples, pagodas, or even churches in southern Vietnam. In private residences, tranh kiếng appears in altar rooms and family mausoleums. The people value these artworks as part of their spirituality and often choose designs that are calm and reverent in nature in hopes of peace and fortune. Every Tết, they are thoroughly cleaned as part of spring preparations.

Giang Lâm Ký, a multi-generational noodle cart in Tân Định Market. Photo via VNExpress.

Some of the most popular motifs on tranh kiếng on noodle carts depict Hằng Nga (The Moon Goddess) or peach-picking fairies. On carts selling sâm bổ lượng, a type of Hoa Vietnamese dessert, are scenes from Tam Quốc Diễn Nghĩa (Romance of the Three Kingdoms) — a historical fiction novel set in 14th century China.

Creating a tranh kiếng, a reversal of expectations

For such a widely loved art form, tranh kiếng calls for very tricky techniques. Painting on paper might already be challenging for some, imagine the level of care brushing colors onto glass surfaces. The one technique that distinguishes tranh kiếng from other mediums is reverse-painting, which gives tranh kiếng its name in English. Pigments are layered onto the backside of the glass, so details that are closer to the viewers are actually on the bottom layer of the painting and are painted first. Painters, hence, need to plan ahead the order of each component of the painting.

Reverse-painting is the key technique in tranh kiếng. Photo via Báo An Giang.

In the traditional way of making tranh kiếng, artisans mix pigment powder with the seed oil of du đồng trees (Vernicia fordii) to create the paint. Only once the paint has dried can the final look of the painting be seen by turning the glass panel over. First, the painter sketches the design on tracing paper, nylon, or carton, and transfers the sketch onto the backside of the glass; though veteran artisans often sketch straight on the glass without a blueprint. The designs can be completely new or based on existing motifs. This step is called “tỉa tách” or “bắc chỉ” in Khmer.

The outline is left to dry, then the artisan will color the spaces using paintbrushes. The order of painting is also in reverse: foreground objects first, then background objects. According to Hoa traditions, seed oil-based paint was the medium of choice back in the day, but today most painters use commercially available epoxy or acrylic paints for convenience, cost-effectiveness, and endurance.

The keepers of old tranh kiếng

I’ve always been most amazed by the traditional painters of tranh kiếng because they have achieved a high level of painting skill without attending any formal art education. They got there thanks to family training, hard work, and generations of legacy experience.

Alas, their role in the creation of tranh kiếng is gradually diminishing due to the use of machines. It’s very likely that any random glass painting you buy from the market today was the product of automation from spray painting or screen printing techniques. This method renders more vivid and diverse colors at a third of the cost compared to traditional craft and is directly making artisans obsolete. Another factor is the weather, as large paintings require a long period in the sun to dry. The limited income can’t guarantee a living wage for painters, so most have left the craft.

Trần Tiên, owner of Vĩnh Huê, a famous tranh kiếng store in Chợ Lớn. Photo via Thanh Niên.

This dire reality has made me much more appreciative of artisans who have held onto their careers. For them, painting on glass is not just a way to make a living, but also a quest to protect their family legacy and the invaluable cultural wealth of the people. In Bà Vệ Craft Village in An Giang Province, one of the pioneer communities of tranh kiếng in the southwestern region, third-generation painters are still creating artworks by hand to preserve the local craft.

When it comes to Chợ Lớn, the breed ground of tranh kiếng once upon a time, the situation is less optimistic: only one or two families are still making tranh kiếng the old way. Vĩnh Huê is one of such stores. In the current era, tranh kiếng is no longer the omnipresent household decoration or past decades when every home had at least one of them. Still, they exist in the altar rooms of old homesteads thanks to the endurance of the medium. Thanks to a resurgence in youth interest in traditional Vietnamese culture, a number of exhibitions showcasing tranh kiếng have been organized, introducing old artworks by Kinh, Hoa, and Khmer artisans from as far back as the 1920s to younger audience members. More hands-on activities like tranh kiếng workshops are also established to give young Vietnamese a glimpse into the creative heritage of their ancestors.

A tranh kiếng exhibition in Saigon. Photo via Phụ Nữ.

It’s impossible to predict how long tranh kiếng will remain in our lives or how long artisans can afford to hang on to their age-old trade. There’s one thing I know for sure, I will always admire the glass paintings on our altar, cause I believe that as long as there is one person appreciating them, their traditional beauty will remain.