Much like their descendants today, schoolchildren of 1930s Vietnam also took art classes as part of their syllabus. In this rare collection of what was essentially our grandparents’ homework, we can surprisingly learn a lot about the daily life of Mekong Delta residents from nearly 100 years ago.

Art is a crucial subject in assisting the development of a young child’s sense of aesthetics, even though not every pupil is excited by drawing lessons. During these hands-on hours, students not only learn how to record what they observe on paper, but also how to appreciate art and life.

Just by flicking through these intricate art assignments by students of the École Primaire de Long Xuyên in 1930, one can feel the pulse of life imbued in every household object and scene portrayed. The scans were archived by the French National Museum of Education.

École Primaire de Long Xuyên, 1920.

Long Xuyên County (as it was then called) received its first administrative designation in the 1860s–1870s. In 1900, Long Xuyên became a province, consisting of three districts: Châu Thành, Thốt Nốt, and Chợ Mới. In 1917, Governor-General Albert Sarraut issued the General Regulation of Education in January 1917, allowing Long Xuyên as a province to establish public schools — which led to the birth of École primaire de Long Xuyên, or Long Xuyên Primary School.

In this artwork collection from 1930, students commonly opted for household items in their still life sketches, like areca nut trays, vases, and even one ghe hầu — an ornate pleasure barge used by members of the upper echelons on vacations. One student chose to draw a pair of geckos, which, as thằn lằn fans at Saigoneer, we feel should deserve more than a 7/10 grade.

It does come as a surprise when we marvel at these sketches because the level of attention to detail was remarkable. From the vases’ elegant inlaid mother of pearl to regal dragon patterns on trays, the students did a sterling job at capturing the artisanship of past craftsmen in their work. Moreover, by looking at these artworks, we can have a glimpse into the range of home items of past Vietnamese that might longer be in use today, such as the areca nut sets.

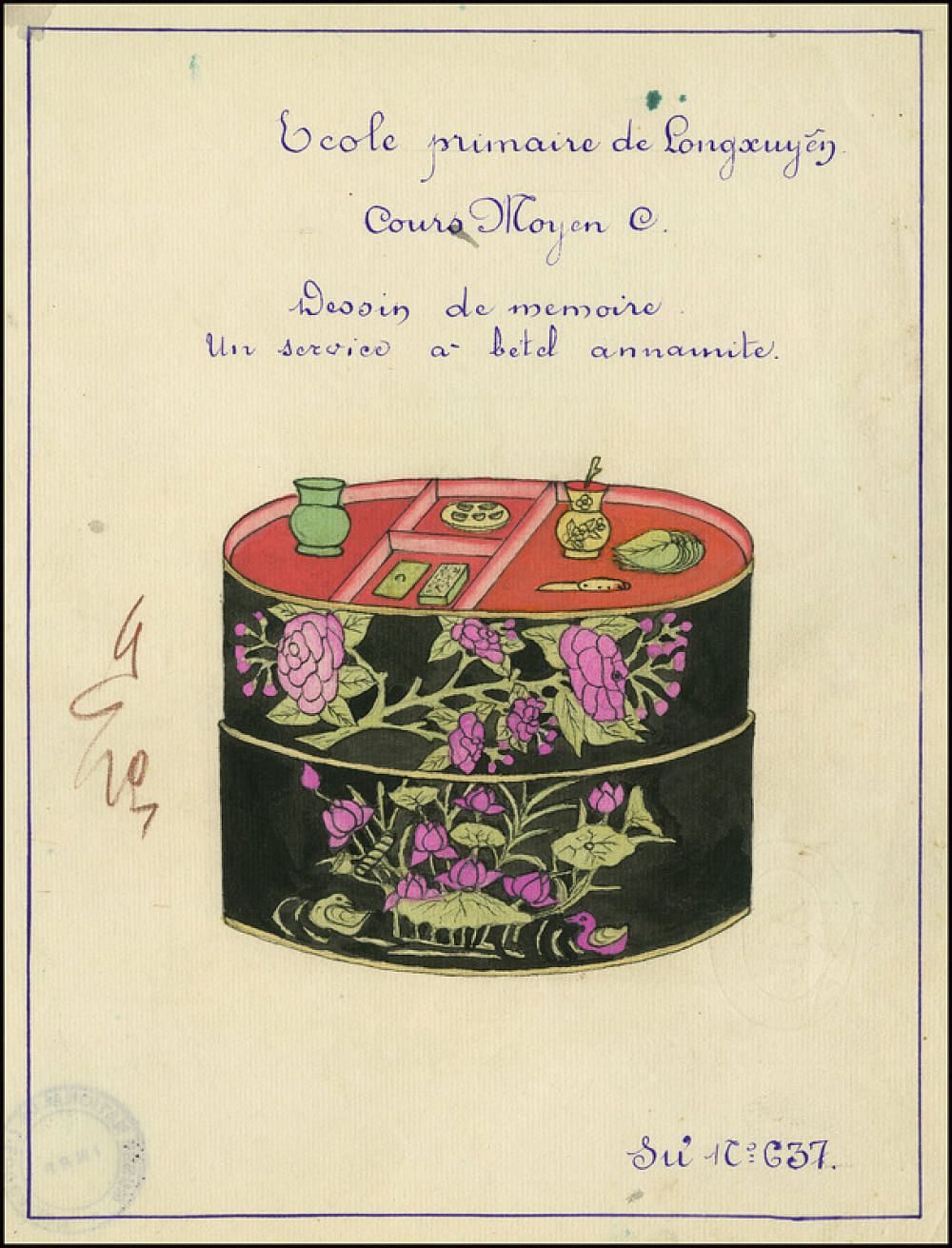

A noticeable motif present in the decorative items that were portrayed by students was the “lotus and duck” subject or liên áp in Vietnamese. The character for áp (鴨), meaning “duck,” has an element of giáp (甲), meaning “first.” This signifies an aspiration to attain high achievement in academic pursuits. Liên (蓮), meaning “lotus,” is a homophone of liên (連), meaning “continuous.” Depictions of “lotus and duck” reflect people’s desire to have good luck in their studies and future career.

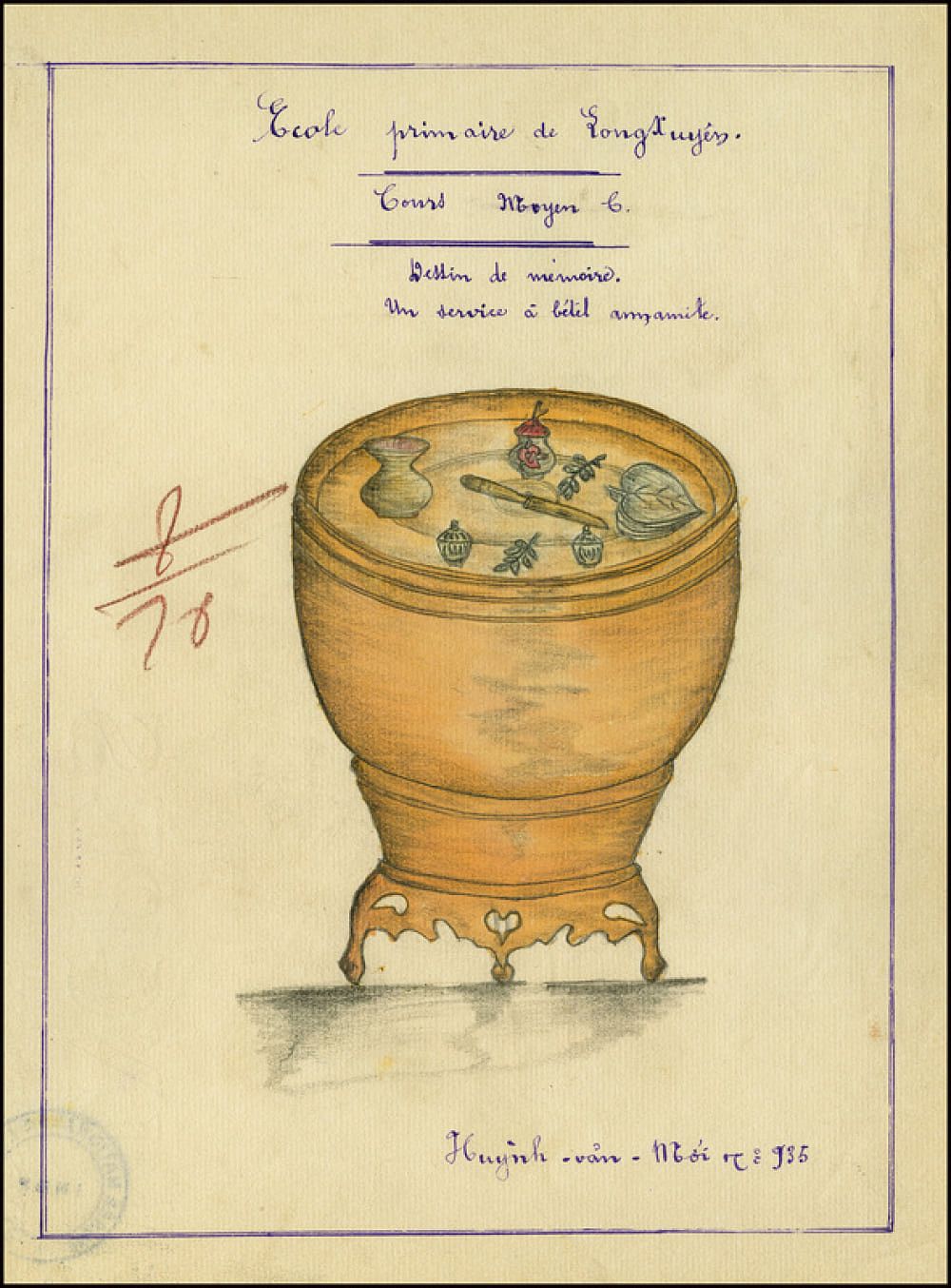

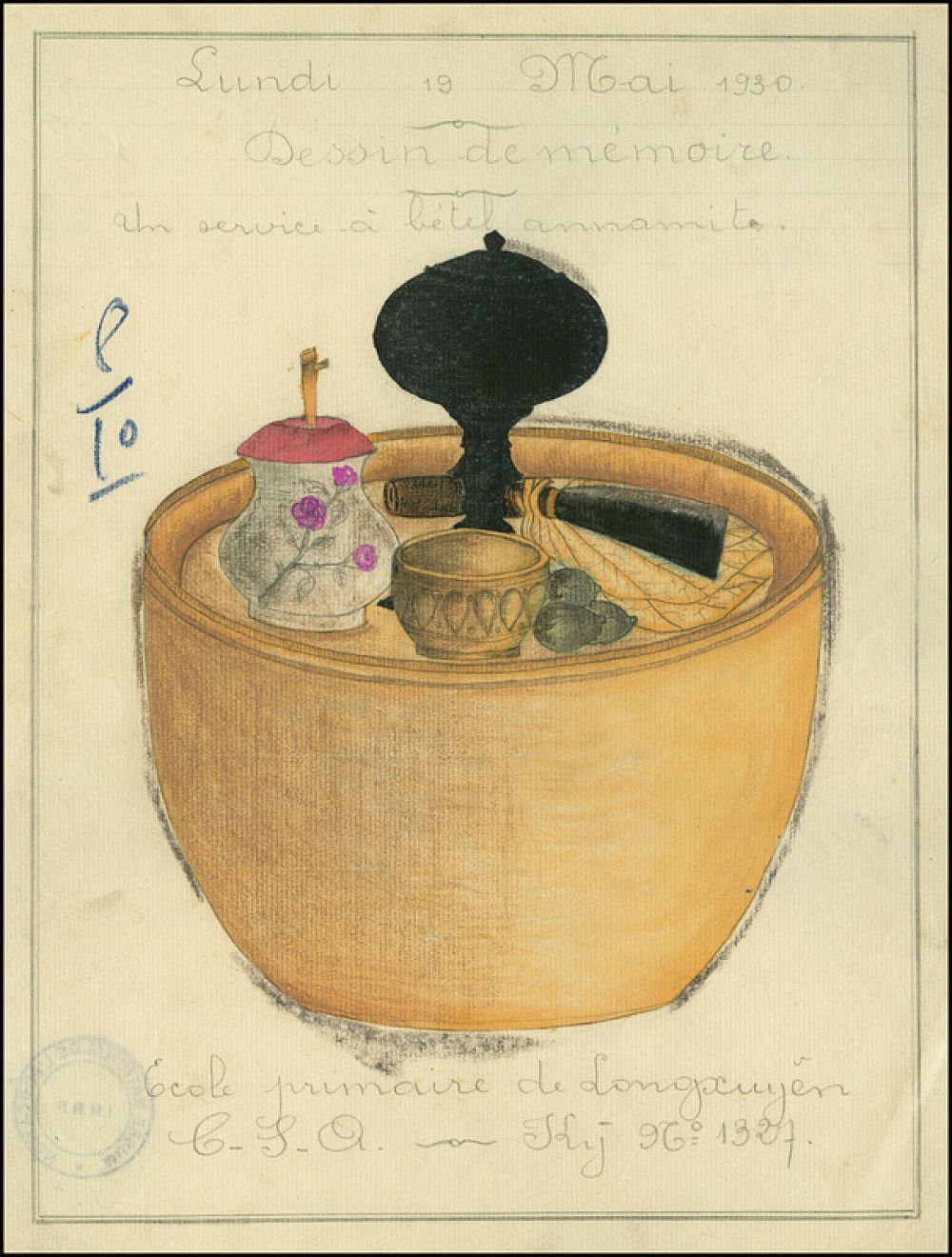

Interestingly, one of the most popular subjects is the areca nut and betel leaf kit used by past generations. A set usually has a tray or lidded pot, a pitcher of lime powder, a cutter, a mixing spoon, dried thuốc xỉa leaves, and a spitting bottle.

In three works by the authors Sư, Huỳnh Văn Mới and Kỳ, we can identify some of these instruments in three different styles, all beautifully crafted to showcase their owners’ financial station. In the set drawn by Sư, the exterior of the box is lacquered and embellished with a “lotus and duck” scene. For the sets owned by Mới and Kỳ’s families, the receptacles were made of bronze.

Three sets of different trầu cau utensils show us the diversity and complexity of our ancestors' areca nut-chewing pastime.

An areca nut box, or cơi trầu, is a multi-component container with a lid, used to store the various tools needed in the consumption of areca nut and betel leaf mixture. Ô trầu, on the other hand, is simply a hollow cylindrical container where everything is kept. According to Trọng Tính, a co-founder of history forum Đại Nam Hội Quán, these setups were usually displayed by wealthy households back then in their living room to flaunt their social status.

Commenting on this set of artworks, Tính also noted that the opulent boat drawn by Trần Tấn Tước isn’t just any mode of transportation commonly seen now. It’s a ghe hầu, a leisure vehicle reserved for river cruise and is decorated with festive flags, a prominent rudder, and other amenities. Today, not many have survived, though two are still kicking around, including the Sáu Bổ owned by Trần Văn Thành, and the Sấm owned by Lê Văn Mưu, also known as Ông Trần.

Marveling at these art assignments by students in the 1930s Mekong Delta, we get to know a delightful facet of the life of past Vietnamese. Areca nut boxes have largely disappeared from our daily routine, and now mostly exist as artifacts in museums. If you’re lucky, there might be one lurking in a corner of the family living room, waiting to be rediscovered. If not, then you’ll probably have to settle for digital images or one of these detailed sketches by students of the Long Xuyên Primary School.

Images courtesy of Trọng Tính.

This article was originally published in 2022.