The several dozen family altars that formed a hodgepodge pile had each been abandoned in graveyards. For many, this would make them extremely inauspicious. But to artist Nguyễn Quốc Dân, they are perfect for making art.

Cemeteries provide the renowned artist with much of the material he needs for his particular style of art, dubbed Tái Sinh-ism, or Taisinism in English. This was evident when Saigoneer visited his 2,000-square-meter home and workshop in Hội An. Empty bottles, jugs, jars, nets, blankets, bags, electronic casings, pipes, tubes, wires, fabrics, flooring, decor, and decorations: The castoffs of capitalism run amok populate the property.

We had been ushered inside after the rambunctious pack of friendly dogs was pushed away from the gate guarding the inconspicuous frontage on the outskirts of town. Dân, immediately identifiable by his beard and long hair, was busy overseeing a new construction project on the site, so Huỳnh Huy stepped in. During a planned bicycle trip across Southeast Asia, beginning in his hometown of Bến Tre, Huy stopped at the Recycling Workshop whose mission and philosophy enticed him to stay for more than a year. He has the scars on his hands to prove his dedication to the art and was the perfect person to explain Tái Sinh-sim to us.

Before showing us around the workshop, Huy shared the ideal place for one of Dân’s pieces to be displayed by way of a question: “What is the most secure building in the world?” Unable to provide the correct answer, he responded: “The UN building. Imagine the world’s leaders sitting around one of these statues.”

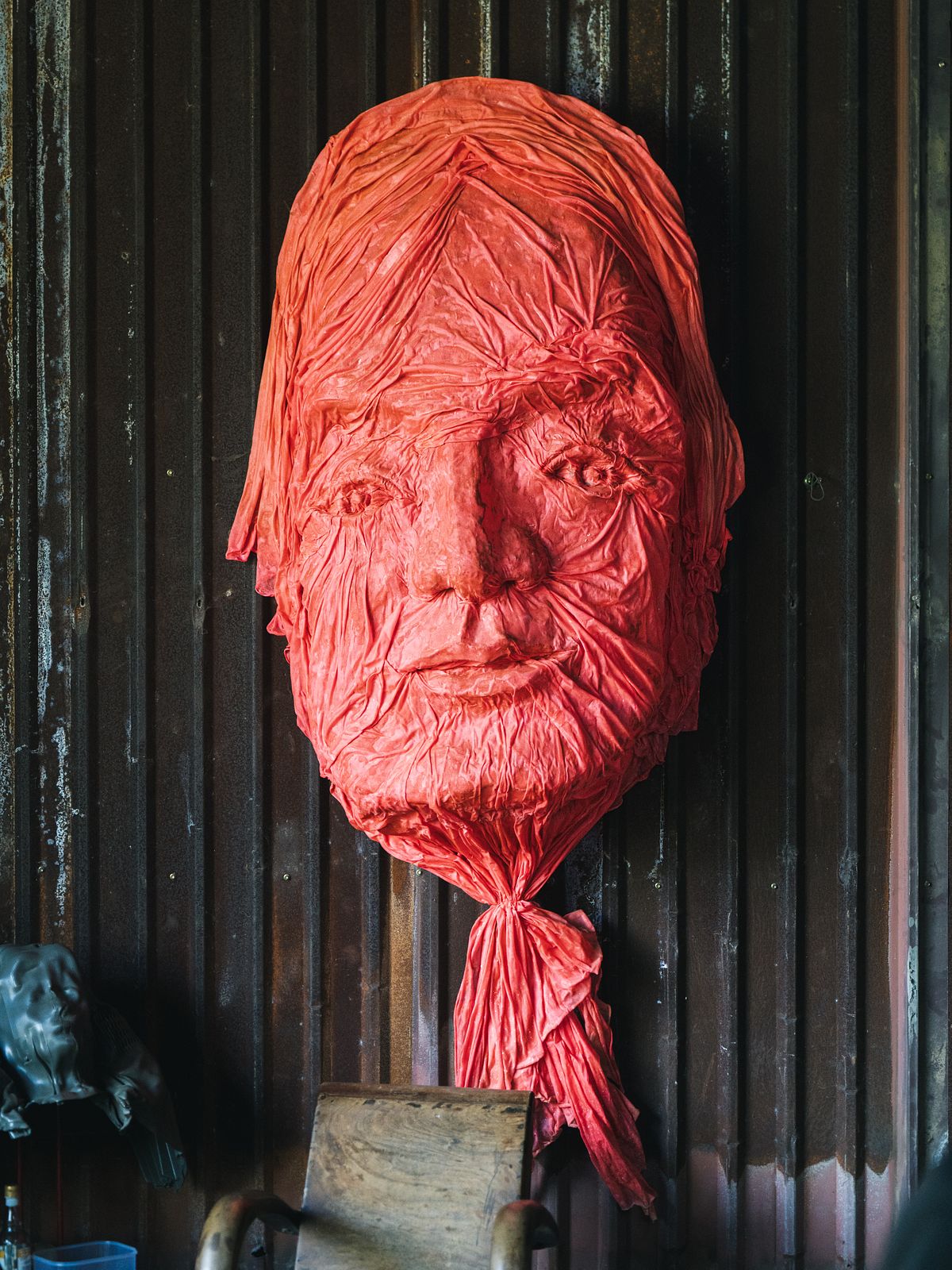

Denim jeans shaped and glued into the form of seated Buddha; a television case melted into the warped visage of a helmet or military mask; a hotel duvet contorted and secured in the shape of a cloaked figure: picturing these works beside the world’s most powerful leaders reveals both Dân’s ambitions for his art and the importance of the message he aims to convey. The cavernous metal space that Huy led us through was built according to Dân’s specifications and only completed after several construction teams called it impossible. Large circular doors at the front and back can be swung open and closed to cast crescent moon shadows.

While Huy pointed out various statues, often asking us to guess what they were made from, Dân appeared to show off the building’s most astounding element. A sunken floor in the middle of the room contains a living tree, while the roof directly above it features a large skylight. Dân has devised some unseen system so that water on the roof can pour in, perfectly mimicking a moderate rainstorm. Dân commenced the downpour, removed his pants, and began making frantic music on the various metal drums, plastic bottles, and discarded surfaces beside the tree. Possessed with an insatiable energy, his solo seemed to stretch on indefinitely while Huy explained how the surrounding art pieces were made.

Many of the works are created by applying “intense heat” to items reclaimed from trash piles and landfills. Time is precious as the melted compounds harden rapidly, so Dân and his team must work quickly to create the intended shapes, often with the support of mannequins and other garbage serving as molds. The process is dangerous, and Huy claims one of the people who helps make them has damaged his fingertips to the point he can now grip burning material. Meanwhile, the team frequently forgoes the face masks useful for protecting against toxic fumes because they are simply too hot to wear. But according to Dân, an artist must be willing to suffer for the work as much as the soul of the material has suffered.

“How much do you think this bottle costs when full, and how much when empty?” Huy asked while lifting a familiar detergent bottle. The answer: VND35,000 full, VND15,000 empty, and then a fee to have it disposed of. The value of items society perceives as worthless trash, compared to what we are paying for, was our entry point into the philosophy of Tái Sinh-ism. This “Rebirth-sim” is not recycling, which aims to give a second life to materials that are of a lower financial value, while up-cycling is the same idea, with a slight reconfiguring of economics. In contrast, Tái Sinh-ism is a complete transformation that elevates items to works of art that cannot be reduced to monetary value, regardless of auction prices or sales receipts. The materials’ lifespans are not extended, but stretched towards eternity with an aim of ensuring they never return to a landfill.

Landfills play a central role in Tái Sinh-ism. Dân spent his childhood scouring trash with his mother, the pittance offered by salvaged garbage providing for their basic needs. He continues to visit these landfills, albeit with a different mindset. Cemeteries also provide much of his material because unscrupulous individuals looking to dump items illegally appreciate the seclusion and taboo that surround them. Many of the mannequins that Dân uses for his molds and for a towering statue of mannequins were found in cemeteries, for example. And as Dân’s reputation has spread, “trash finds us,” Huy said, noting how supporters will often arrive with various scraps.

Dân resting in a landfill. Photo via Nguyễn Quốc Dân's Instagram page.

While Dân’s work and lifestyle may sound wacky, he is not the art world outsider he may sound to be. His creative talents were recognized at a young age, and he received generous assistance to study at the HCMC University of Fine Arts, where he studied and practiced more conventional contemporary styles. Understanding the foundations, traditions, and aims of these works, while amassing trash materials in his rented Saigon room, led him to an artistic epiphany. Dân believes that all art must address the questions of the day. The questions that elicited cubism and modernism, for example, have been addressed by many practitioners over the past decades, while the question of what to do with the mind-boggling amount of trash our species churns out remains unaddressed. Tái Sinh-ism is his response to that question.

Dân’s experience in navigating the art world, to say nothing of his charisma, has surely helped him achieve a level of success. Quantified by social media followers, news coverage, or public shows, including a recent VCCA exhibition in Hanoi, he can be considered a well-known artist. This notoriety allows him to proselytize for Tái Sinh-ism, with curious locals and foreigners making a pilgrimage to his studio when in Hội An. Meanwhile, he provides classes and workshops for children to help them nurture their creative spirits while instilling at a young age a revolutionary approach to garbage.

Nguyễn Quốc Dân's exhibition at the VCCA. Photo via Hanoi Times.

You don’t need to be a full-throated convert to Tái Sinh-ism to take a trip to Dân’s workshop. He will welcome anyone, and if you go in with an open mind, you are likely to depart with a new way of thinking that will return any time you see a pile of trash on the street or left over after a museum gallery opening. At the very least, you will appreciate the genuine kindness and humble eccentricity of Dân and his marvelous works of art.