There are two things that disconcert older-generation Vietnamese Americans in Little Saigon from those around them: fusion food and the arts; both of which evoke nothing but strangeness. Intolerable strangeness.

Filled with nostalgia, they live in their pasts while memories may make them sob or rejoice as they drift across static time. What do they consider Vietnamese food? Plain rice, fish sauce, and water spinach can send them over the moon. Anything fusion represents loss. So it is with the arts.

Ann Phong doesn’t want to be a misfit. But she is, more or less, in Little Saigon. “Vietnamese Americans, for many generations, have hardly changed,” she professes, “the first generation never ventures out of [their] Vietnamese cultural zone or appreciates innovative arts.”

'Our Ocean, Your Ocean,' acrylic with found objects.

Ann Phong would have probably starved in a garret if she were not teaching at California State Polytechnic University in the Pomona Department of Art. She teaches for survival, and because of her passion for art. In a community where art is still deemed a vanity, and artists vagabonds, Ann Phong is somewhat of an outcast. She never minds. She paints her pain. Her flight was a pain. Her car accident — great pain. It seems that the word “pain” is destined for Phong, but it allows her art and life to flourish.

For refugees that fled across the ocean, the sea on moonless nights evokes horrors. It conjures the darkness of their flight when the use of lights could result in death. Ann Phong’s paintings disquiet us with jarring depictions of such scenes. She portrays the violent ocean, boats sinking and people struggling in vain. Who would want to relive those traumatic moments? Her artwork remains moored to this theme and never leaves her gallery because what collector would want to hang memories of such painful, perilous journeys across the Pacific?

Her daring strokes also lament how the ocean is strewn with trash, spilled oil, dead fish, bottles and bloody waves: the ocean’s pain. Ann Phong’s artwork denounces human brutality and environmental negligence by asking: “Who is killing the ocean?”

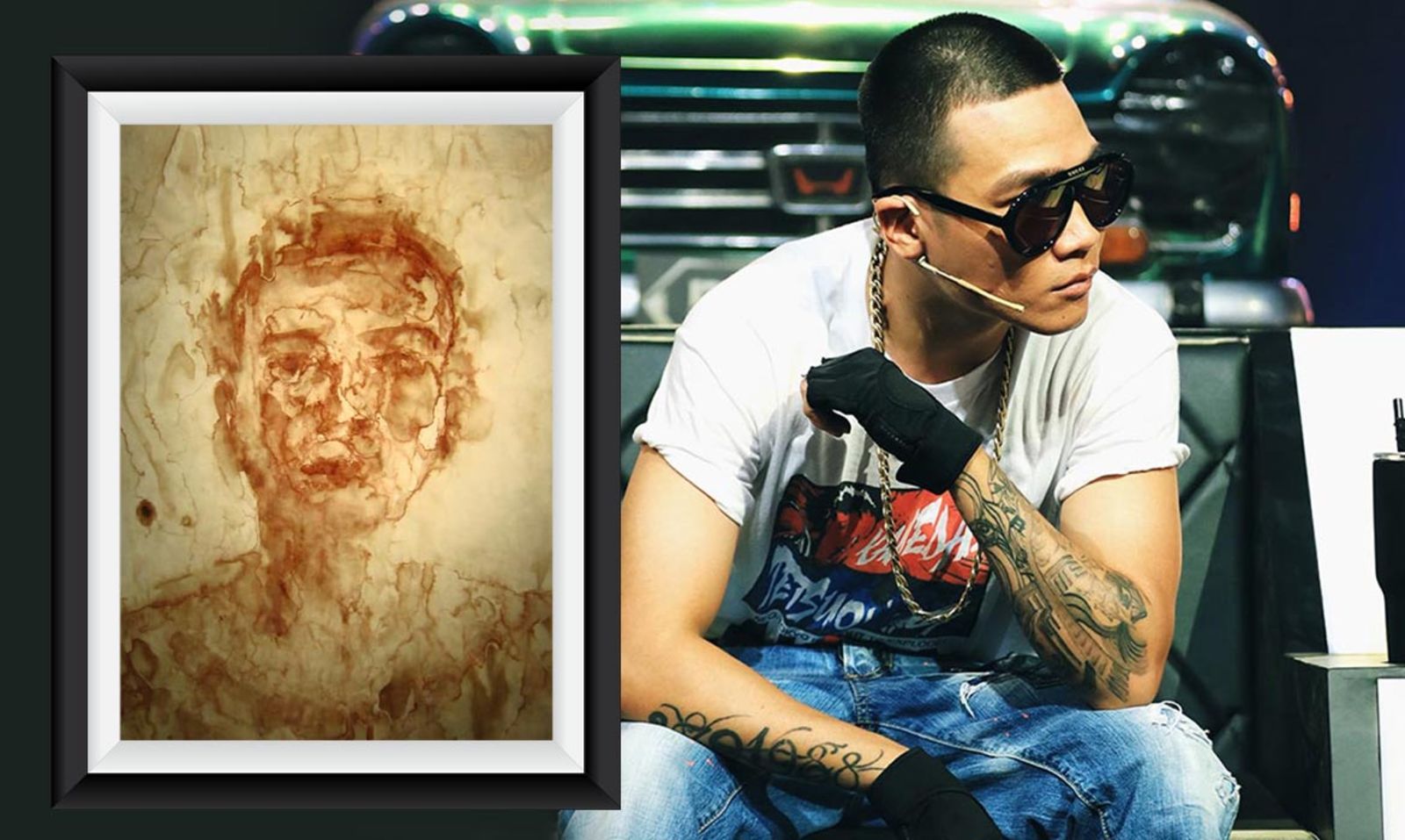

"I draw human abundance and apathy and ignorance which damages our nature," Phong says. To do so she occasionally uses animal carcasses as material to create hallucinatory clarity that continues to grip viewers’ minds long after they have turned away from the paintings.

Her blend of colors and natural materials is unique and adds layers of charm and meaning to the artwork. Such choices are no gimmick, especially because her peers prefer to hang ponds filled with lotus, a beautiful lady sitting beside lilies or a joyous boy atop a buffalo. “Why don’t you paint those familiar images of Vietnam? It’s money for jam,” an older guest who stopped by her gallery urged her one day before leaving with a disdainful smile. Undeterred, Ann Phong quietly hangs up her paintings, one after another, like beacons of hopes.

Ann Phong observes that the arts are more appealing to younger generations of Vietnamese Americans. As the former Board President of VAALA [Vietnamese American Arts and Letters Association] (2009-2018), she notes: “VAALA attracts more and more young volunteers who cannot speak Vietnamese and expect me to present my work in English.” Ann Phong speaks English and her exhibitions typically draw young visitors as she aligns herself with progressive artists who are willing to take risks and understand Vietnamese American pop culture while pouring their emotions into their work. In contrast, Ann Phong notices that the group of artists who earned their degrees in Vietnam and were deeply influenced by Vietnamese culture isolate themselves from the larger English-speaking art community. Their work is rooted squarely to the past, in their homeland, pickled for ages in the brine of its shadow.

Ann Phong’s early days in the US resemble her paintings: a mesh of colliding paths, intersecting and outstripping one another. She spent her first frosty winter in 1981 at her sister’s house in Connecticut. Growing in a tropical region where the sun never ceases to shine, Ann Phong found Connecticut unbearable and she left when her boyfriend convinced her to join him in California. Juggling ESL classes, dental assistant school, and a part-time job at an orthodontist’s sapped her energies. “I drank plenty of coffee every day to stay calm and nimble,” she admits.

Her talent for art became evident when the orthodontist, watching how Ann perfectly bent procedure wire, encouraged her to pursue dentistry and promised to share his clinic with her when she graduated. But during this period, Ann Phong was involved in a car accident that required time in the hospital that allowed her to examine her life in America. “What is my dream?” Phong recalls asking herself which led to her “giving up everything to pursue my passion of becoming an artist.”

After graduating valedictorian from an art school, she embarked on frequent jaunts abroad. “I’ve exhibited extensively,” she says with a smile.

'Nature in the Polluted Cities,' acrylic with found objects,

If Ann Phong compromised her work to lead a life of extravagance, she would crank out kitschy paintings for commercial gain en mass. “I don’t paint for a living,” she admits, “my job is teaching the arts at the University of California Polytechnic in Pomona.”

Whenever she has free time, she paints. Her artwork captures the fierce transformation of identities hemmed in powerful blocks of colors that push across space via the turmoil of lines and circles. It is an art of chaotic feelings. “I see the ocean inside me,” she says, “and I draw my community struggling out of the dark sea.”

She points at a painting of dark colors. It depicts a moonless sea with an immense black hole; an abyss. Bodies float, fish swim towards the Sun. Her brushes nudge the painting towards a blast. She draws Vietnamese women as pawns on a chessboard played by men who seem to lose their power in exile. Those vulnerable and voiceless women, however, become more strident in America.

Phong’s art also articulates her fury about the exploitation of natural resources in Vietnam by transnational corporations. Elsewhere, her dry humor comes across in pieces such as the bronze drum of Vietnam, which she says alludes to the old generation of Little Saigon. “Those people resist changes, so detach themselves from the youth.”

Colors are treacherous and Ann Phong involves them in her ploys. She splashes her paintings with shining, lively shades to attract viewers, not to convey frivolous, insouciant, ostentatious messages about life. “I use found objects, trash to show how nature hurts,” she explains. “If we don’t value our environment today, we will be toxic tomorrow. If human wins, nature fails.”

If one gazes deeply under Ann Phong’s flashing colors, one finds jarring darkness. Why should we demand joyful art from an artist with a great reason to be joyless? Despite this, Ann Phong is still relentlessly searching for a silver lining in life and art.

Her journey is arduous, her passion immense. Ann Phong strives every day to pass on her love of art to her students through her lectures and to the community via her artwork. To the students, she urges, “be yourselves! [in art]”

Ann Phong doesn’t just teach about her own style and perspective. She also introduces many Vietnamese American artists. She carries her artwork wherever she journeys to and reaches out to everyone who shares her philosophy regarding art. She convinced the formal representatives of Vietnamese American communities to buy her painting as a gift to the University of California in Irvine.

Phong has learned to love the community where her art can affect and be affected, more or less, through community media and newspapers that value her passion for art. Her paintings are, in every sense, disconcerting, but purposely so. She dares say that "stillness" narcotizes bona fide arts. The artist, like lava, must seethe in every work.

Competition is fierce, especially when technology careens art along. Every artist has to battle for prominence with modern methods. Ann Phong is no exception. She incorporates technology with the help of Huynh Thuong Chi who helps her install a sound chip behind each art piece so viewers can hear her stories behind it. A popular Facebook user herself, she has gained a following by posting every piece she creates. Uncomfortable as she sometimes is with technology, art has taught Ann Phong to embrace and explore original and unfamiliar creations. When introduced to an innovative way of blending technologies such as virtual reality and augmented reality with art, her face beams with elation, followed by a simple, “wow!”

'Yesterday's Precious, Today's Trash.'

For the future of the arts in Little Saigon, Ann Phong imagines a “very trendy” cultural center where everyone can mingle with everyone else, old and young, to relish the arts. Exhibitions, talks, and performances will enlighten people and bring them closer to different forms of arts. The idea of the artist as an outcast will then acquire a layer of dust since everyone, in the fullness of time, will desire something beyond their abundance. Arts will fill that emptiness.

[Images courtesy of Ann Phong]

Quynh H. Vo holds a PhD in English from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa where she teaches and researches globalization and literature, Asian American interdisciplinary studies, Vietnamese American literature, and neoliberalism in American transnational literature. Her writings have appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Journal of Vietnamese Studies, the Peace, Land, Bread, and elsewhere.