This week, we trace the saga of colonial Saigon’s monuments to French republican statesman Léon Gambetta (April 2, 1838 – December 31, 1882), whose statue was commissioned twice by mistake and then installed in three successive locations before its final disappearance in 1955!

Best remembered for his heroic efforts to defend France during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, French statesman Léon Gambetta played a pivotal role in the founding of the Third Republic (1870-1940) and helped to transform it into a régime based on parliamentary supremacy. He also served briefly as France’s first minister (president of 'Le Grand Ministère') from November 14, 1881 to January 16, 1882.

Léon Gambetta (April 2, 1838 – December 31, 1882) by Alphonse Legros, 1875.

Gambetta's premature death in December 1882 inspired genuine public mourning in France, and two years later a grand monument to the great man – comprising bronze statuary by sculptor Alexandre Falguières (1831-1900) and a decorative pedestal by architect Paul Pujol (1848-1926) – was raised in his hometown of Cahors. The monument featured a large bronze statue of Gambetta dressed in a fur coat and addressing a crowd, flanked at its base by the figures of a sailor and a mortally wounded naval infantryman, recalling the glorious role played by Gambetta in the defense of his country.

The original Alexandre Falguières-Paul Pujol monument to Gambetta in Cahors.

In subsequent years, streets and squares all over the French empire were named after Gambetta, but the government of Cochinchina decided to go one step further by commissioning a replica of the Cahors monument, right here in Saigon.

In the mid 1880s, it was decided that May 5, 1889 – the 100th anniversary of the meeting of the Estates General, which set in motion the events leading to the French Revolution – should be celebrated as the Centenary Festival of the Revolution (Fête du centenaire de la Révolution). Accordingly, in April 1889, all French colonial governors were informed by Assistant Secretary of State for the Navy and Colonies Eugène Étienne that on May 5, every public monument in every colonial capital must be illuminated and decorated with flags and bunting. He also “authorised the Governor-General of Indochina on that day to inaugurate the statue of Gambetta in Saigon” (Gil Blas, April 22, 1889).

In the event, the Gambetta statue was solemnly inaugurated at the intersection of Boulevard Norodom [Lê Duẩn] and Rue Pellerin [Pasteur] a day earlier than originally planned on May 4, 1889 in the presence of Governor General Étienne Richaud and Saigon Mayor Roch Carabelli.

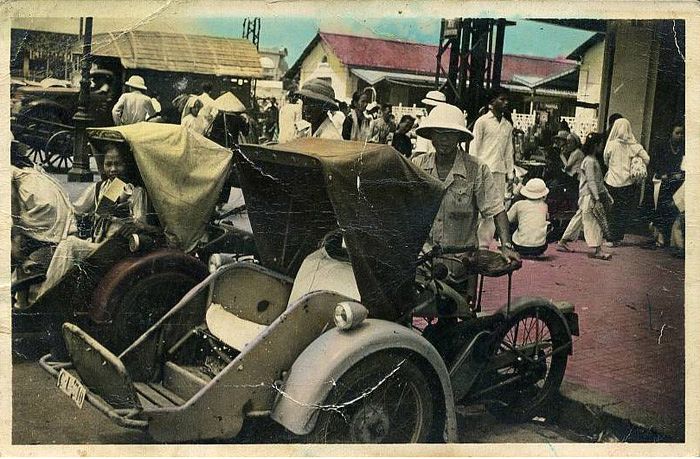

Boulevard Norodom, Saigon (before 1914) and the same intersection today.

Saigon's Statue de Gambetta (before 1914).

In subsequent years, reaction to the new monument was not entirely favorable. Gerrit Verschuur, in his book Aux colonies d’Asie et dans l’Océan Indien, remarked: “What that great orator ever did for Saïgon, nobody knows.”

However, it was the incongruity of the statue’s heavy winter clothing in tropical Saigon which was singled out for the greatest criticism.

George Durrwell, in his book Ma chère Cochinchine, trente années d'impressions et de souvenirs, février 1881-1910, described Gambetta's attire as “somewhat inappropriate in our sunny Cochinchina.” Writing two years later, A Maufroid commented less diplomatically in his 1913 book De Java au Japon par l’Indochine, la Chine et la Corée that the statue “seems almost to menace the Governor General’s official residence with his vehement gestures: a bronze Gambetta, who struggles under a thick coat, like a North Pole explorer. The natives, who sweat all year topless, gaze with amazement at his incomprehensible clothing.”

It was Durrwell in 1911 who revealed the intriguing backstory of the commissioning of the Gambetta monument:

“The Gambetta monument... has a history which could serve as a theme for some amusing production in the Théâtre du Palais-Royal. Here it is in a nutshell:

In response to the premature death of Gambetta, seeking to interpret faithfully the common sentiment, our local assembly decided to perpetuate his memory by raising a dignified statue to him in one of our Saigon squares. The funds were voted by acclamation, and one of our honorables, then on leave in Paris, was charged with commissioning the work.

Our man, thus given a mandate, made his choice among the great artists of the capital, and that choice was good; a few months later, the desired monument arrived safely. Everything was going well.

But we had reckoned without the patriotic zeal of our deputy. The confusion resulting from his informal intervention was not long in coming. One morning, the Mayor was informed that another large box labelled “statue – fragile” had just arrived at his address. A duplicate statue had been mistakenly produced and delivered to Saigon! The excitement was great, but so was the embarrassment, because a large monumental statue is rather more difficult to refuse than a simple parcel sent cash on delivery.

The Mayor had a good practical solution: the duplicate was given to the deputy who had rashly ordered it, and he was obliged to pay for it. It was cruel but logical, and in our good Cochinchina, where money comes easy, a compromise solution was not even offered. In this way, Saigon is even now in possession of two Gambetta statues. The one we all know is proudly located in the sunlight of boulevard Norodom, while the other is stored and long forgotten, buried for years in the white wooden coffin in which it once made its long and unnecessary trip to our overseas territories.”

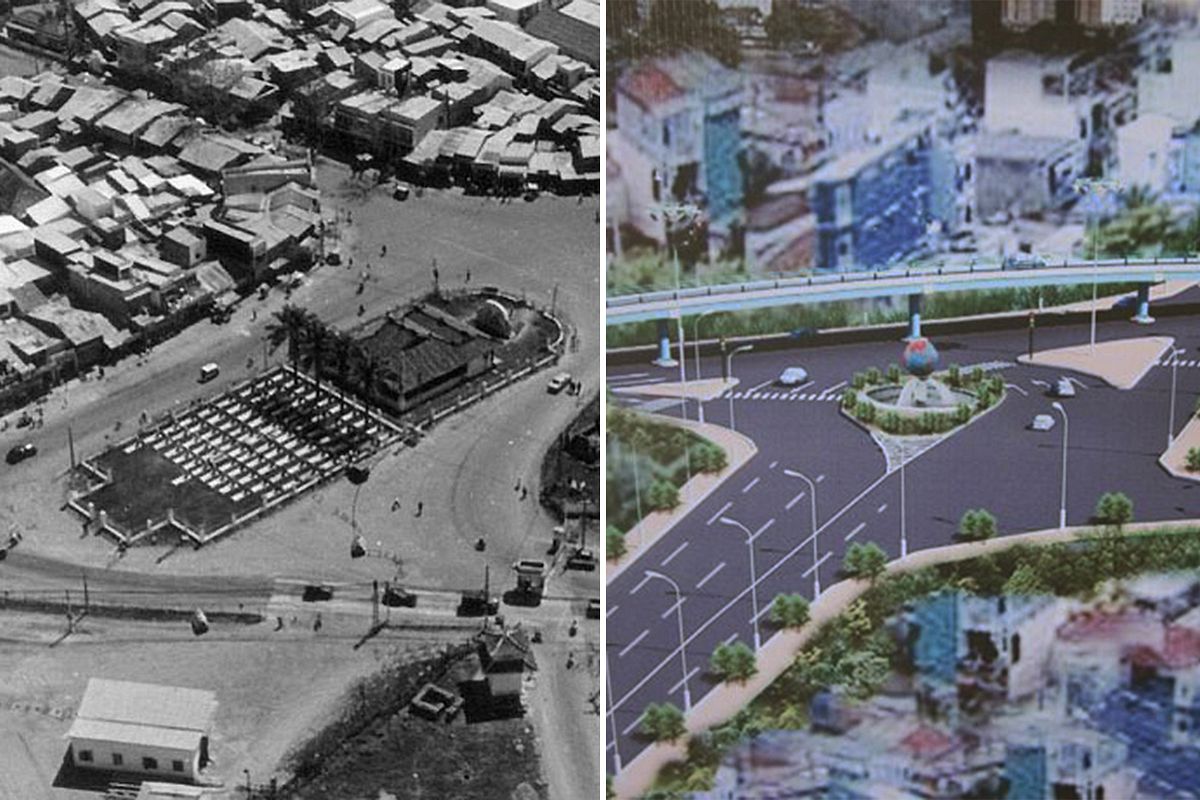

The Gambetta monument remained at the intersection of Boulevard Norodom and Rue Pellerin until 1914. In that year, the new Halles Centrales (Bến Thành Market) was inaugurated and the old city market on Boulevard Charner was demolished. In place of the old market, a large open square named Place Gambetta was laid out, and the monument was painstakingly moved eight blocks southeast and installed at the square’s center.

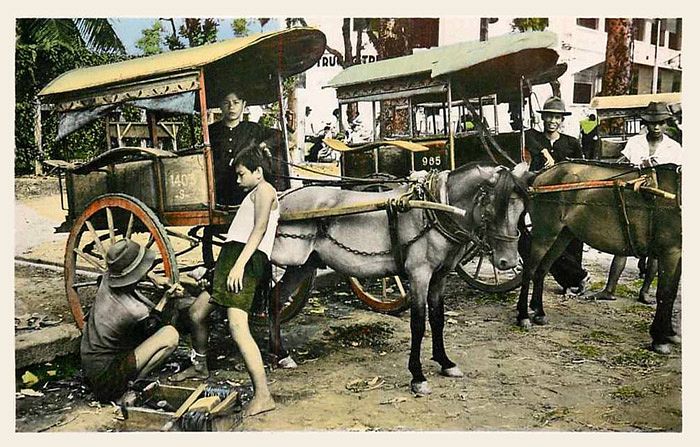

Place Gambetta, vue du Café de la Terrace (1914-1925) and the present-day Bitexco Tower on the same site.

However, this would not be its last resting place. Less than 10 years after the monument’s installation on Place Gambetta, it was decided to redevelop the square with a brand new General Treasury (the Trésor General of 1925, designed and built by Brossard et Mopin) overlooking Boulevard Charner. To facilitate this, the Gambetta monument had to be relocated again, this time 10 blocks west to a central location in the Jardin de Ville (later the Parc Maurice Long, now Tao Đàn Park). It would remain there until 1955, when it was removed to facilitate the extension of Trương Công Định Street (modern Trương Định Street) through the middle of the park.

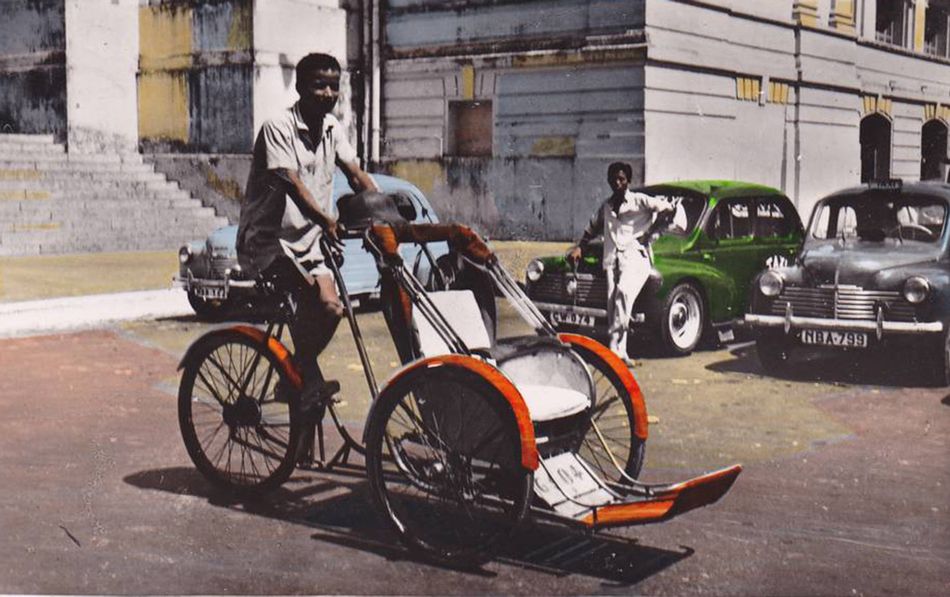

Saïgon's Parc Maurice Long, Statue de Gambetta (1940s).

To this day, the ultimate fate of the itinerant Gambetta monument and its unfortunate twin remain a complete mystery.

Tim Doling is the author of the walking tours book Exploring Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2014) and also conducts 4-hour Heritage Tours of Historic Saigon and Cholon. For more information about Saigon history and Tim's tours visit his website, www.historicvietnam.com.