Once a downtown canal, a breeding ground for crocodiles and the heart of Saigon’s own Chinatown, Hàm Nghi is one of the city’s three widest boulevards.

Like several other major city thoroughfares, Hàm Nghi Boulevard began life as a waterway. Late 19th-century scholar Pétrus Ký tells us this waterway was known in Vietnamese as the Rạch Cầu Sấu (“Crocodile Bridge Creek”) because of the pools which once lined its banks, in which crocodiles were bred for their meat (Pétrus Trương Vĩnh Ký, Souvenirs Historiques sur Saïgon et Ses Environs, 1885).

The Crocodile Bridge Creek ran from the Saigon River as far as the modern Hàm Nghi-Pasteur junction, where it met another canal, which extended along what is now lower Pasteur Street, and eventually connected with the Junction Canal, the forerunner of modern Lê Lợi Boulevard. Before 1867, the Crocodile Bridge Creek was used mainly by merchants to access the old city market on what the French designated Rue Chaigneau (modern Tôn Thất Đạm Street).

The Crocodile Bridge Creek is pictured on this map from the mid-1860s.

At the start of the colonial period, the wharfs on both sides of the Crocodile Bridge Creek east of the junction with Rue d’Adran (modern Hồ Tùng Mậu) were named Rue No. 3, while those between the Rue d’Adran junction and the lower Pasteur Street canal were designated Rue Dayot.

During the 1860s, the French authorities encouraged large-scale immigration from China’s Guangdong province, with a view to the further development of the economy. Emanating mainly from Guangzhou city and neighboring Zhaoqing prefecture, many of the Cantonese newcomers chose to settle between the Crocodile Bridge Creek and the Arroyo Chinois (Bến Nghé Creek) in Saigon, establishing a second Chinatown with its own assembly hall (the Guangzhao Assembly Hall) at Cầu Ông Lãnh.

The bridge over the entrance to the Crocodile Bridge Creek (filled in 1867-1868) may be seen clearly in both of these photographs of the Maison Wang-Tai under construction in 1867. Photos by John Thomson.

In 1867, these new Chinese immigrants were joined by one of Cochinchina’s most famous Cantonese businessmen, the opium dealer Wang Tai, who in that year built his imposing headquarters, the Maison Wang-Tai, on the riverfront right next to the Crocodile Bridge Creek entrance (see Wang Tai and the Cochinchina Opium Monopoly).

The Crocodile Bridge Creek was filled in 1867-1868, forming a 56-meter-wide thoroughfare. In 1870, to accommodate the merchant boatmen, a replacement city market was built several blocks away, on the west bank of the Grand Canal (modern Nguyễn Huệ Boulevard). Thereafter, the old Rue Chaigneau market continued to function as a local market.

On May 14, 1877, in recognition of the fact that a large number of its residents were Chinese settlers from Guangdong province, the new street was designated Boulevard de Canton.

During the first 20 years of the colonial era, numerous government buildings were installed at the lower end of the boulevard, including the Direction du Port de Commerce (Commercial Port Directorate) and the Service du Pilotage (Piloting Service). After purchasing the Maison Wang-Tai in 1881, the Customs and Excise Directorate had it rebuilt in 1886-1887 as the Hôtel des Douanes (Customs House) (see Foulhoux’s Saigon).

The opening of the Saigon-Mỹ Tho railway line in 1885 brought further changes to the boulevard, which by this time extended west as far as the Rue Mac-Mahon (modern Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa). Saigon’s first rail terminus was situated at the riverside end of Boulevard de Canton, between the Customs House and the Commercial Port Directorate, and the railway line itself ran west along the center of the boulevard, before heading out towards Chợ Lớn and Mỹ Tho. A large railway atelier was built immediately to the west of the Boulevard de Canton-Rue Mac-Mahon junction (see The Saigon-Mỹ Tho Railway Line).

A train waits to depart Saigon for Mỹ Tho on July 20, 1885, the opening day of the railway line. Image courtesy of Maison Asie-Pacifique (MAP).

On February 24, 1897, the boulevard was split into two separate roads either side of the railway track, each road named after a French admiral – Rue Krantz on the northern side and Rue Duperré on the southern side.

Another significant landmark was built on the boulevard in 1906 in the form of the École des Mécaniciens Asiatiques (School of Asian Mechanics, now Cao Thắng Technical College), students of which included Nguyễn Tất Thành (Hồ Chí Minh) in 1911 and Tôn Đức Thắng in 1915.

Read Part 2 of the historic street's story here.

Tim Doling is the author of the walking tour book Exploring Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2014) and also conducts Heritage Tours of Saigon and Chợ Lớn. For more information, visit www.historicvietnam.com.

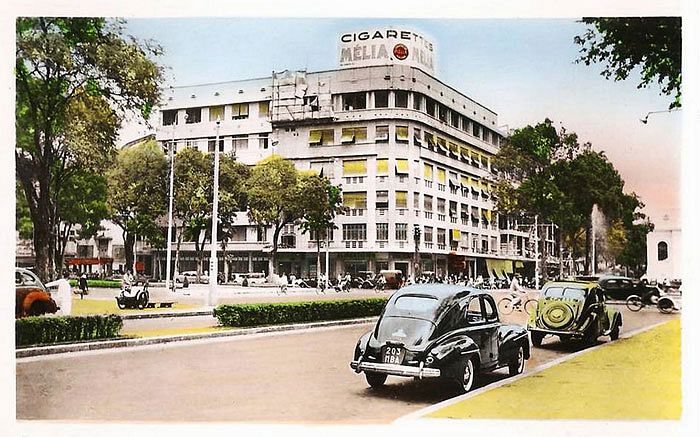

[Top image via Flickr user manhhai]