From loudspeakers broadcasting construction anthems during wartime to melancholic ballads mourning vanished street corners, Hanoi's soundtrack reveals a city that has never quite learned to live in its present tense.

Hanoi has become, in these last few years, a vast construction site. The city transforms rapidly — a metamorphosis most visible to those who've left and returned. After several years abroad, I began to understand the emotions of those who abandoned the city in 1954 to head south, or departed in the 1960s for Eastern Europe to build socialism in Berlin, Warsaw, Prague, and Sofia, while American bombs tore their beloved Hanoi apart. Skyscrapers now sprout from the skyline like mushrooms after rain, concrete rainforest replacing the greenery that once covered the metropolis's outskirts.

Hanoi's skyline. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The prevailing mood among young people responding to this rapid change is optimism. Like myself, many of my peers feel no astonishment when encountering pedestrian areas in North America, Europe, or, right nearby, in Singapore. In Vietnam's major cities like Hanoi, Hải Phòng and Saigon, you'll find the same malls, high-tech centers, and sprawling suburbs as anywhere in the west. Though perhaps you won't feel quite the same confidence when your plane descends into Shenzhen or Shanghai, where even westerners begin to suspect they're lagging in history's race.

“Socialism works, finally!” I hear this refrain from both my Canadian left-wing professors and Vietnamese orthodox Leninists populating Facebook comment sections. This excitement echoes the early years of socialist construction in the north during the 1960s and 1970s, when the Hanoi government received financial, material, and ideological support from the Soviet world to erect the first nhà tập thể — communal apartment blocks.

The euphoria of construction and how it outpaced reality

The brutalist nhà tập thể pales beside today's luxurious skyscrapers in Cầu Giấy, west of Hanoi. But when the country was caught between wars, these buildings symbolized socialist development, monuments to the glorious, ever-growing Vietnamese working class born of French colonialism and their fight for liberation. This achievement was celebrated in revolutionary songs broadcast through urban loudspeakers on every corner. In Phan Huỳnh Điểu's ‘Những Ánh Sao Đêm’ (Night Stars), the windowpanes of nhà tập thể were compared to stars in the galaxy, illuminating Hanoi's sky:

Làn gió thơm hương đêm về quanh,

Khu nhà tôi mới cất xong chiều qua,

Tôi đứng trên tầng gác thật cao,

Nhìn ra chân trời xa xa.

Từ bao mái nhà đèn hoa sáng ngời,

Bầu trời thêm vào muôn ngàn sao sáng,

Tôi ngắm bao gia đình lửa ấm tình yêu,

Nghe máu trong tim hòa niềm vui, lâng lâng lời ca.

The fragrant night wind circles near,

Our new-built homes still gleam from yesterday.

I stand atop the highest floor,

My eyes drift far where sky and city fade.

From roof to roof, the lights bloom bright,

The heavens sparkle, joining every flame.

I watch each home, each heart’s warm fire,

And feel my blood flow into song—

A joy that carries me away.

Nhà tập thể, mimicking the style of khrushchyovka blocks in the Soviet Union, was under construction in Hanoi. Photo via Thanh Niên.

Phan Huỳnh Điểu, one of Vietnamese socialist realism's greatest names, wrote ‘Những Ánh Sao Đêm’ in 1962–1963, while living in the communal house of the Vietnam Songwriters Union. His son, songwriter Phan Hồng Hà, recalled how the lights from the Kim Liên communal house, then in mid-construction, inspired Điểu when viewed from atop the union building. Born in Đà Nẵng and having built his early career in Quảng Ngãi, the revolutionary artist always looked southward, yearning to fight for it after moving to the north in 1955. He eventually returned to the south in 1964, serving as an artistic cadre spreading revolutionary spirit beyond the 17th parallel. His longing, as expressed in ‘Những Ánh Sao Đêm,’ was finally fulfilled:

Em ơi, anh còn đi xây nhiều nhà khắp nơi,

Nhiều tổ ấm sống vui tình lứa đôi,

Lòng anh những thấy càng thương nhớ em.

Dù xa nhau trọn ngày đêm,

Anh càng yêu em càng hăng say,

Xây thêm nhà cao, cao mãi.

My love, I still must go and build new homes afar,

Where joyful couples share their life and dreams.

And in my heart, I find I miss you more.

Though day and night keep us apart,

The farther I go, the more I love you—

And build the houses higher, ever higher.

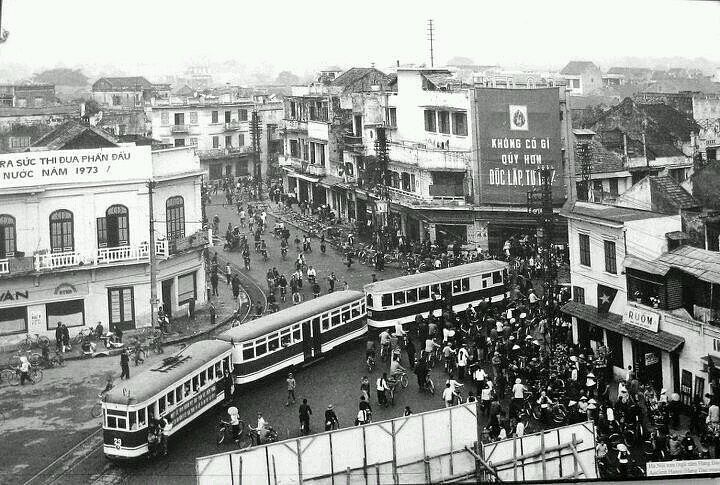

Revolutionary songs erupted at every corner of northern urban life, replacing what had been a “petit bourgeois” metropolis, as Phạm Tuyên sang in ‘Từ Một Ngã Tư Đường Phố’ (From a Street Corner). While red ideals' fate remained uncertain in the south, they occupied the highest position in northern hearts. Tuyên sang: “From a small street corner, I can already see the future coming near / In every figure, head held high, striding swiftly down the sidewalk.”

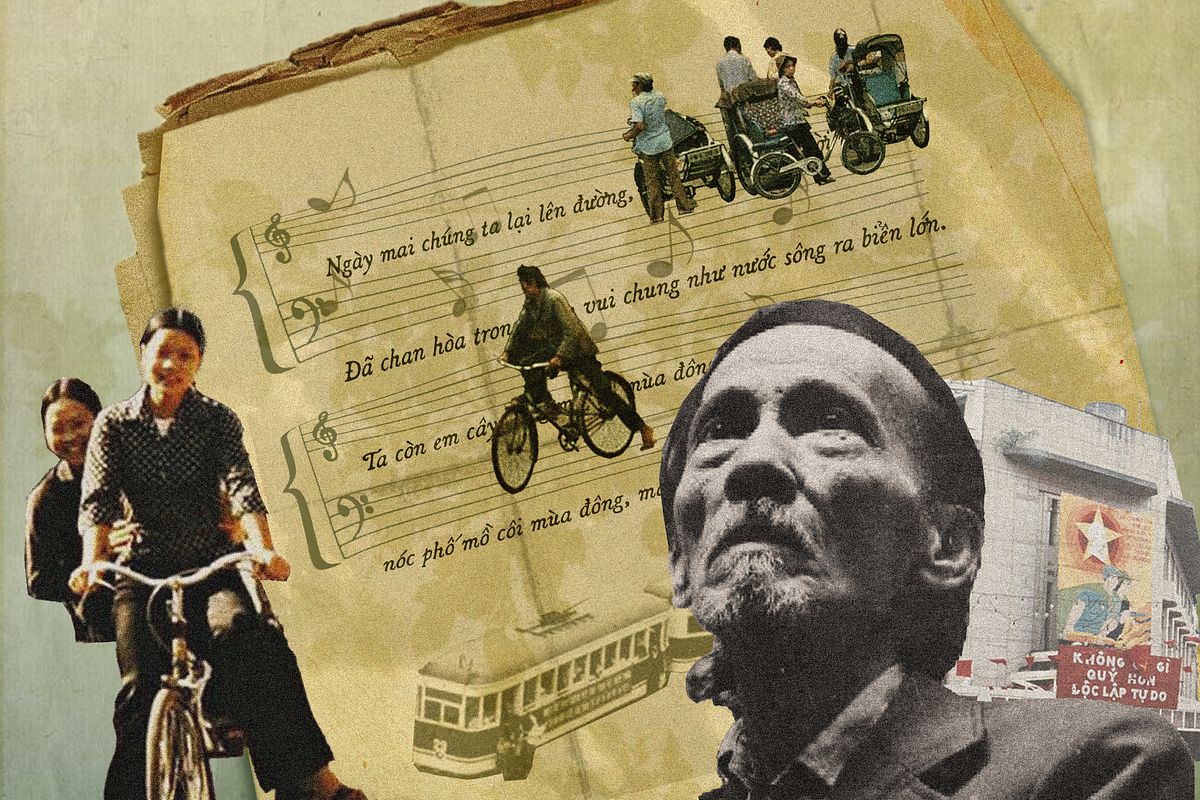

The metropolitan life of Hanoi, 1973. Photo via Bcdcnt.net

Written in 1971, ‘Từ Một Ngã Tư Đường Phố’ was more than Phạm Tuyên's artistic depiction of northern metropolitan life during the American War. Like a masterful conductor, he directed radicalized youth through song to move faster than history's natural pace:

Xây cuộc sống mới toàn dân gái trai vững vàng,

Nhịp đời cuộn nhanh nhanh như vượt trước bao thời gian.

Đường phố của ta vẫn đang còn hẹp,

Nhường bước thúc nhau đích xa cũng gần,

Tự hào đi trong tiếng kèn tiến quân vang ngân.

We build a new life—men and women, steadfast all,

Life's rhythm surges fast, as if outpacing time itself.

Our streets are still narrow, yet we make way for one another,

Urging each other on—our distant goal now feels so near,

Proudly we march to the echo of the trumpets calling us forward.

Phan Huỳnh Điểu dreamed of building the future while Phạm Tuyên urged youth to outpace the present. These imperatives revealed the revolutionaries' special relationship with time: they claimed to represent the future. Hoàng Vân's ‘Bài Ca Xây Dựng’ (The Song of Construction) became the anthem of this future as it would — and should — eventually materialize on Vietnamese, Chinese, and Eastern European soil. It captured the emotions of those who had just moved into newly constructed nhà tập thể. For Hoàng Vân, Hanoi's new urban setting promised a new life where new personhood would flourish.

This new life wouldn't remain localized to North Vietnam; it would spread globally with the working class's forward march through history. Vân sang proudly: “Tomorrow we set out once more / Toward new horizons waiting ahead,” followed by "Our hearts have merged in a common joy like rivers joining the boundless sea." Written in 1973, when northern victory seemed certain as American soldiers departed from the south, the song mentioned warfare only once, “[believing in the new life] in the smoke of bombs” but also “under the moonlight.” Public reception proved so enthusiastic that during the postwar period, it was performed repeatedly by socialist art's finest voices, like Ái Vân, throughout the European socialist world — just before its collapse.

‘Bài Ca Xây Dựng’ (1973), performed by Ái Vân in East Germany in 1981.

Yet these optimistic construction songs fundamentally mismatched their era's reality. While they excited people and helped them endure hardship, the actual situation differed drastically: American bombardments, urban populations fleeing to the countryside, extreme poverty, industrial failures, bureaucratic delays, so on and so forth. Construction projects stalled and showed degradation shortly after completion. Essentially, socialist construction became more psychological than material. These utopian songs held people together — especially urban dwellers who suffered most — rather than letting them fracture.

The rise of urban nostalgia

The 1970s' optimism evaporated as the country entered the 1980s, witnessing Soviet socialism's mass collapse and economic liberalization marked by the Communist Party's Sixth Congress in 1986 (Đổi Mới). Socialist optimism gave way to a newly emergent genre: urban nostalgia. The most famous example was Phú Quang's ‘Em ơi Hà Nội Phố’ (Darling, Hanoi Streets), an adaptation of Phan Vũ's poem of the same title.

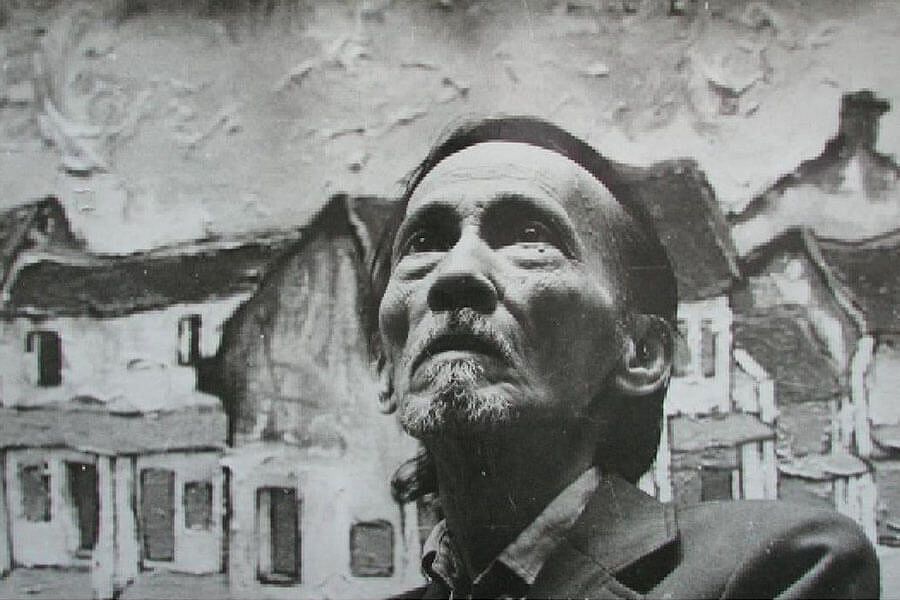

What makes the song extraordinary is that poet Phan Vũ wrote the original in December 1972 during the US Air Force's Operation Linebacker II, which bombed Hanoi, hoping to pressure the north into cease-fire negotiations on terms acceptable to the United States. With its depressing, nostalgic tone, Vũ never published it, sharing it only with his intimate circle. He read it directly to Phú Quang in 1987, after the songwriter relocated to Saigon. Deeply moved by ‘Em ơi Hà Nội Phố,’ the composer selected 21 of 443 lines from the original work to craft Hanoi's new anthem.

Khâm Thiên street in Hanoi, after an American bombardment. Photo via Vietnam News International.

Rather than praising revolutionary symbols, ‘Em ơi Hà Nội Phố’ evoked a much older Hanoi — one that might have been condemned as “petit bourgeois” before Đổi Mới:

Ta còn em cây bàng mồ côi mùa đông.

Ta còn em, nóc phố mồ côi mùa đông, mảnh trăng mồ côi mùa đông.

Mùa đông năm ấy, tiếng dương cầm trong căn nhà đổ,

tan lễ chiều sao còn vọng tiếng chuông ngân

I still have you—the orphaned banyan in winter.

I still have you—the lonely rooftop in winter, the orphaned crescent moon in winter.

That winter, the piano sounded in the crumbling house,

And after the evening mass, the echo of the bell still lingered.

Phú Quang's melancholic masterpiece awakened a new aesthetic in Hanoi-inspired songs, including 'Cẩm Vân's ‘Hà Nội Mùa Vắng Những Cơn Mưa' (Hanoi Season Without Rain) and Trần Tiến's ‘Hà Nội Ngày Ấy’ (Hanoi of Those Days). These songs mourned not old socialist ideals but far older urban values — French colonial street scenes (especially the distinctive trees planted during that era), feudal myths (like Lê Thái Tổ's sacred sword), and traditional Hanoian customs overlooked during the socialist construction years. Consider these verses from Trần Tiến's ‘Hà Nội Ngày Ấy’:

Hà Nội giờ đã khác xưa

Kiếm thiêng vua hiền đã trả

Bạn bè giờ đã cách xa

Ngỡ như Hà Nội của ai?

Hanoi is changed from days gone by,

The holy sword of the wise king restored.

Friends have wandered to places far,

Whose Hanoi do I see before me now?

Hanoi, as depicted in urban nostalgic songs, was like Hanoi in Bùi Xuân Phái's painting. Photo via Kiệt Tác Nghệ Thuật.

Rather than celebrating post-Đổi Mới modernization and the country's opening to the wider world, Trần Tiến lamented lost Hanoian values. But he reached beyond recalling heroic days of resistance against invaders. He summoned remembrance of feudal Hanoi as Vietnam's cultural center. He mourned the old Hanoian elite who guided the city through both colonialism and revolution. Regardless of their politics, what mattered was their defense of Hanoi's metropolitan values, elements slowly vanishing under postmodern gentrification.

The nostalgia of Phú Quang, Cẩm Vân, and Trần Tiến wasn't simply a reaction to rapid urban development during both the 1970s and the contemporary era of economic liberalism. It responded to the promise of building a dreamworld during wars, revolutions, and hardship, which was fulfilled mentally but not materially. For so long, Hanoi's spirit resided in the future while actual life remained trapped in the past. People endured the pain and trauma of American bombs and radical social revolution while being told to feel perpetually optimistic. They never inhabited their present.

What will tomorrow's nostalgia look like?

Now that urban modernization has actually been accomplished, at the cost of demolishing old socialist icons like communal houses, what will future Hanoi generations remember and feel nostalgic about? In the early days of the 2010s, people expressed nostalgia for the subsidy era when life was simpler, governed by socialist morality and modest infrastructure. But it seems a wealthier, more dynamic life is now winning Hanoi's heart.

Perhaps this is the cruel logic of Hanoi's emotional architecture: we are always living in someone else's future, always mourning someone else's present. The revolutionaries of the 1960s and 1970s sang of futures they would never inhabit, building dreams in melody while American bombs destroyed stone and mortar. Their children learned to miss a past they were forbidden to mourn at the time. And now, as glass towers replace concrete blocks, as luxury malls erase subsidy-era markets, we're constructing yet another promised land that today's youth will someday lament when it, too, becomes obsolete.

In front of Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục Square, 1973. Photo via Vietnam News Agency.

What makes this cycle particularly poignant is that each generation believes its present will finally be the one that lasts, the one that fulfills all previous promises. The socialists thought their communal houses would stand as monuments to a permanent revolution. The nostalgists of the 1980s believed they were preserving something eternal about Hanoi's soul. Today's developers and their young, cosmopolitan customers imagine they're building a modern city that will endure.

But if history teaches us anything, it's that Hanoi will continue to transform, and each transformation will feel like both progress and loss.