“The lonely sound of a lute cannot cure your pain. You need Tơ’s singing to bring you serenity.”

So Tơ sings: “Our love is poured out just like the river that never returns. Our small boat lets itself be guided by deep and restless waves on the river.”

A scene from Mê Thảo, Thời Vang Bóng.

But how could the mournful ca trù song ever cure Nguyễn’s heartbreak? How could the timeless art form serve as a salve for the ravages wrought by the capricious, overpowering forces of the world? Why should anyone expect it to?

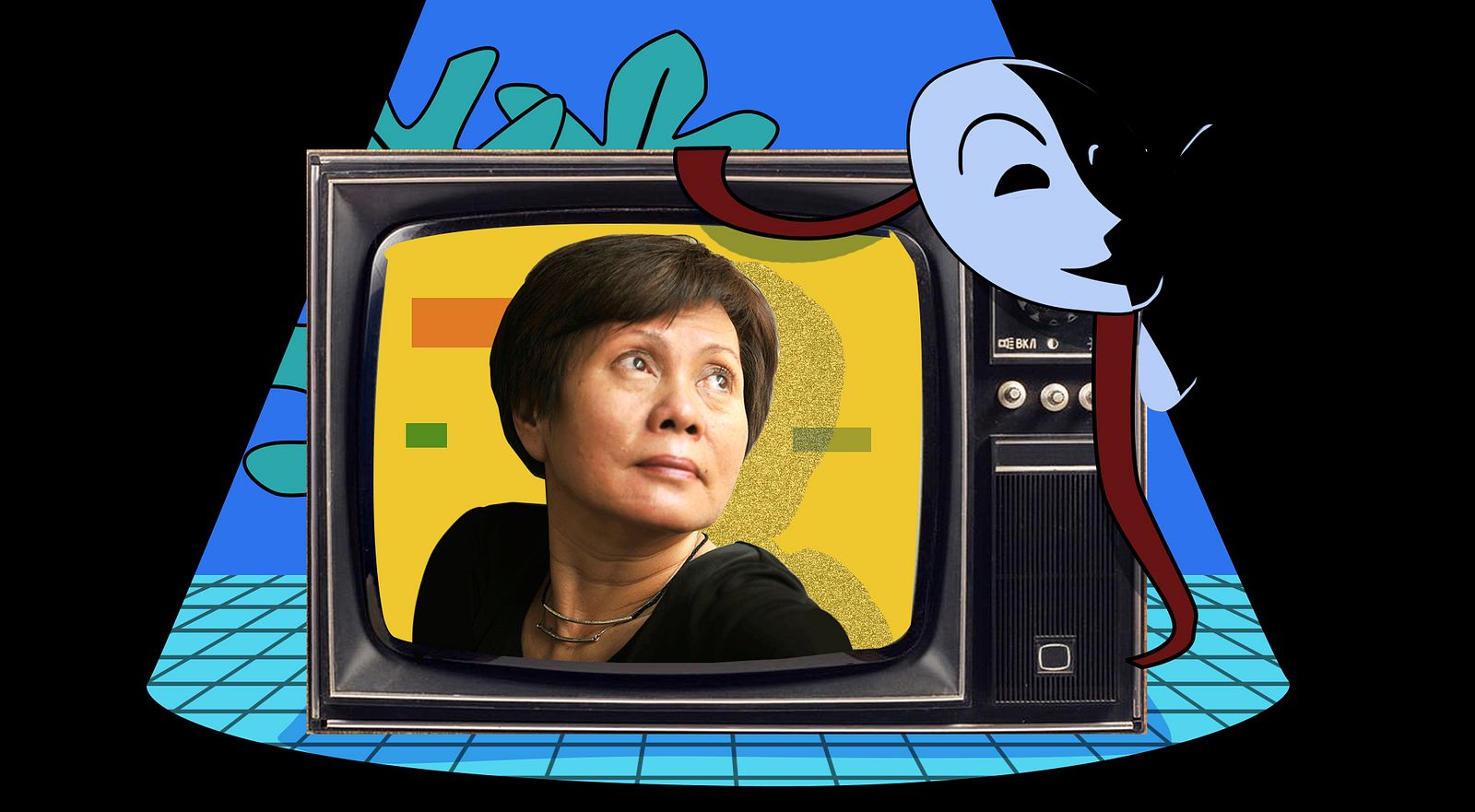

This is the situation that plays out at the end of Mê Thảo, Thời Vang Bóng (The Glorious Time in Me Thao Hamlet), one of the more powerful modern Vietnamese films. Eighteen years later, the song drifted across the audience at Saigon’s District 4 Flamingo Theatre during a staging of the play Diễn Viên Hạng Ba (C-List Actor). This is no coincidence; Việt Linh directed the film and wrote the script for the play, and the music serves as an apt metaphor for her artistic endeavors as a whole. As she addressed the audience after the show, she noted that she simply loved the song and wanted to showcase it again. For as gifted and accomplished as a creator across numerous genres as she is, what stands out most profoundly about Việt Linh is this dedication to creating a community to share her passions with.

“Do what makes you happy, as long as it is free of vanity and extravagance,” Việt Linh’s father, also a scriptwriter, told her when she announced her plans to pursue film at a young age. In 1975, she was assigned to assist with editing and screenwriting at Saigon’s Giải Phóng Film Studio. Five years later, at the age of 28, she left to study in the then-Soviet Union for five years before returning to Vietnam to embark on a career that includes directing six films between 1986 and 2002, as well as writing movie scripts such as the popular Tôi Thấy Hoa Vàng Trên Cỏ Xanh (Yellow Flowers on the Green Grass), penning numerous books that introduce Vietnamese readers to the history and techniques of film, and operating two theaters that aim to share her enthusiasm with younger generations.

Scene from Mê Thảo, Thời Vang Bóng (The Glorious Time in Me Thao Hamlet). Photo via Phố Văn Blog.

Many filmmakers develop a specific style that they rarely deviate from while obsessing over the same themes, subjects, actors and camera angles. It’s why five minutes into a movie one can recognize a Wes Anderson, Quentin Tarantino or Michael Bay production. The same cannot be said for Việt Linh. The films she has directed span eras, aesthetics and subjects. 1999’s Chung Cư (The Building) takes a gritty look at a modern-day Saigon apartment complex, while her 1986 debut Nơi Bình Yên Chim Hót (The Peaceful Place Where Birds Sing) renders a nostalgic wartime Mekong village, and 2002’s Mê Thảo, Thời Vang Bóng focuses on an area outside of Hanoi at the turn of the 20th Century. The style of each of her films, from camera work to plot to pacing to characters, differs considerably as well.

In 1988’s Gánh Xiếc Rong (The Circus Comes to Town), a group of urban performers upends the lives of the poor villagers in a small, rural area. On its surface, the work invites ruminations on the divide between city and countryside existences. But digging deeper, one encounters a philosophical argument about complicity and the inherent goodness of humanity. Superstitions and social stigmas underpin dissections of fate and, ultimately, happiness in Dấu Ấn Của Quỷ (The Devil’s Mark) via the relationship between a leper, a woman born with an ominous birthmark, and an escaped convict, while the pull between modernity and isolation and managing grief rest at the forefront of Mê Thảo, which depicts a landlord’s attempts to isolate himself from emerging technologies following his fianceé’s fatal car accident.

Scene from Gánh Xiếc Rong (The Circus Comes to Town). Photo via TPD Movie.

When deciding what to portray, Việt Linh says she is drawn to a central message. Yet, this message shouldn’t be understood as a simple moral lesson or thesis, but rather the examination of a complicated issue via nuanced, multidimensional characters in direct contrast to modern movies that eschew complexity or creativity for tired tropes, stereotypes, and predictable endings that follow standard plot beats.

Perhaps contributing to her movies’ diversity, Việt Linh doesn’t craft the scripts for the movies she directs, despite being a gifted and experienced writer. Rather, she told Saigoneer: "I have a profound fondness for literature and read regularly, which has brought me to realizing the whirlpool of similar-minded thinking that exists in literature. Furthermore, I hope to prolong the life of a piece of work, thus spreading the values of such great literature across the audiovisual art scene."

Việt Linh at work. Photos courtesy of Việt Linh.

And while she offers praise for auteurs of many nationalities, it’s notable that Việt Linh works primarily with adaptations of Vietnamese literature. So despite splitting time between Vietnam and France, where her husband and daughter live, she maintains a strong connection with the country, explaining: “I believe that the ideal art arises when one can glean from the people and scenes of a nation to extract a universal, worldly message; as such, the ideological, the humanism, and the aestheticism become ‘cultural touchpoints’ through which the artist reconciles the gap between his or herself and the audience. It is evident that works that deal with or embody a distinctive national voice to them tend to invite more interests from and evoke empathy in the world audience.”

One gets the sense that Việt Linh likes having a mercurial style because of how it allows her to indulge her creative impulses while surprising audiences. She told Saigoneer that people were shocked that her third film, 1988’s Gánh Xiếc Rong (The Circus Comes to Town), was shot entirely in black and white because color had just become the norm for Vietnamese movies and people were attracted to the novelty. The monochrome film stock she chose actually made it more expensive to make the movie, but she refused to compromise because she believed the story demanded it. This principled stubbornness may be a product of her passion, and key to her success.

Việt Linh (left) at the Berlin Film Festival in 1992. Photo courtesy of Việt Linh.

Việt Linh's achievements include awards from the Swiss Fribourg Film Festival, Bergamo Film Festival in Italy and the Namur International Film Festival in Belgium, but her insistence on maintaining certain artistic principles has made her career as a filmmaker difficult at times. Years have stretched between projects because of her need to find the right script, a process made significantly more difficult because of the limited range of what the national film studios will fund. And the budgets she receives may surprise audiences familiar with the tens of millions of dollars given to projects produced in other nations. Chung Cư, for example, was made with less than US$200,000. Moreover, while claiming that good works exist regardless of the gender of its creator, she notes being a female in a male-dominated field has presented challenges. Working with heavy equipment in the field is physically taxing, as is the “sexism and prejudices against women in general,” she says.

The collision of Việt Linh’s passion for unadulterated art and industry realities have resulted in a degree of disappointment. She explains: “With writing, an art relatively independent and self-governing, I rarely have any regrets upon revisiting them. Film and theater, on the other hand, are collective arts — especially considering the highly restricted and controlled conditions of the Vietnamese creative scene. Therefore, I am very often anguished by the compromises I have had to make with the situation, and consequently, the work is always plagued with a sense of unfulfillment.”

This dissatisfaction with collaborative projects helps explain why she claims that the work she is most proud of is not a film, but rather her books comprising Tủ Sách Điện Ảnh (A Cinema Collection) and her film education initiative Hồng Hạc (Flamingo Theatre).

A Cinema Collection is comprised of essays in Vietnamese on filmmaking compiled from articles she has written since 1998. In them, she explores important films, directors, styles and techniques. She offers a very wide-reaching focus and features artists from around the world, including Krzysztof Kieslowski from Poland, Takeshi Kitano from Japan, Pedro Almodovar from Spain, Nanni Morretti from Italy, Nuri Bilge Ceylan from Turkey, and Andrei Zviaguintsev from Russia. She also pays attention to Vietnamese filmmakers such as Nguyễn Hồng Sến, Khương Mễ and Nguyễn Thị Thắm.

Việt Linh’s writing is not the only way that she seeks to educate Vietnamese people about the world’s great films and filmmakers. Four years ago she founded the Flamingo Cinema Club to screen and then discuss important works every Sunday. The scheduling format has changed over the years, but recently, they have been selecting one director per month, showing a different work each week that best typifies some aspect of their style. The films selected are neither high-profile mainstream works nor obscure arthouse or experimental films, rather ones that adhere to the vague but simple criteria that they must be good movies.

Photos via The Flamingo Cinema Club Facebook Page.

Reflecting on her career, Việt Linh once said, “I want to be like the coconut tree in my hometown. It is an ordinary tree, not high-priced but useful; any part of it can be used. I once saw a dead [coconut] tree that was lowered to make a small bridge for the kids.”

Due to her busy schedule, Việt Linh handed over daily operations of the Flamingo Cinema Club to Thùy Linh two years ago, and when we met with her to learn more about the club, Linh offered candid examples that exemplify this philosophy. She said that Việt Linh will often read a news story about a person in a dire situation somewhere in Vietnam and make all efforts to help, including traveling to provide them with assistance directly, or relying on her reputation and connections to involve people with means. And when COVID-19 shut down all public gatherings, she refused to leave the actors who perform in her theater without income; instead paying them to practice as normal.

After suffering a stroke that left her unable to perform the physically demanding elements of making films, she transferred her energy and focus to Hồng Hạc.

A scene from the play Tấm và Hoàng Hậu by Hồng Hạc Theatre. Photo by Alberto Prieto.

In the same way her films differ from blockbuster efforts, her plays deviate from some conventions of modern theater. The performances are typically understated, with characters delivering lines the way people talk in normal life, as opposed to over-the-top recitations. The lighting also stands out, as its dramatic use resembles lighting used for films, engendering a certain cinematic aesthetic to the performances.

Việt Linh has no illusions about the current or future popularity of staged plays. Relegated to the margins in a world filled with an increasing amount of entertainment options, plays receive far too little attention, even compared to independent films, art exhibitions or literature. Yet, this seems of no importance to her, as she explains: “I have an innate passion for creativity, so anything that has to do with arts for me never feels like chore or responsibility — rather, they are a source of joy.”

A scene from the play Tấm và Hoàng Hậu by Hồng Hạc Theatre. Photo by Alberto Prieto.

Such motivation requires flexibility in how she funds her theater. Friends and corporate leaders will often buy numerous tickets as a means to support it. Simply being able to cover all the costs, including paying the performers, is enough for Việt Linh, as it's a matter of art, and not a means to make money. This past July, for example, Viet Anh School in Binh Duong Province bought all of the tickets for a performance of Tấm và Hoàng Hậu (Tam and the Empress) at the Saigon Opera House. In a positive sign that theater can still attract an eager audience, by 8:30am, the steps of the iconic building were filled with extravagantly dressed locals eager to enjoy the show, regardless of the early hour.

While Tấm và Hoàng Hậu was a Hồng Hạc performance, Việt Linh neither directed it nor wrote the script. Rather, the interpretation of the classic Vietnamese folk tale was penned by young writer Phát Nguyên. In the introduction to the English-language version of the script, Việt Linh offers a telling statement that reveals her priorities and philosophy: “When I brought Tam and the Empress of CKT Drama Club, which belongs to the University of Social Sciences and Humanities, to Hồng Hạc and turned it into a professional play, many people thought that I was reckless. I was anything but reckless. First, Hồng Hạc’s motto is sharing the passion, and supporting all the entertaining ideas of the youth. Secondly, art is a creative subject based primarily on contemplating reality and aesthetic emotions. You can always improve your skills, yet emotions and aesthetics can only be raised from the bottom of your heart and your culture.”

At the end of her address to the audience following her play Diễn Viên Hạng Ba, Việt Linh noted how the characters in the play were not a biological family, but had decided to become a family. This, she said, was a modern form of family. Indeed, as cultures change and worlds connect in different ways, perhaps families increasingly consist of people that do not share a bloodline, but rather common beliefs, interests, emotions and values. If so, Việt Linh’s career could be considered an act of forming a family. Via her films, plays, theaters and educational efforts, she brings people together, and like any good family member, helps to create a warm, nurturing environment for people to thrive in.