It's 2009 and I'm running a workshop for a large group of unemployed jobseekers in Sydney, Australia.

We are discussing our “greatest accomplishment in life” when a very reserved 60-year-old Vietnamese man says, “I made a feature film at a famous studio, it’s been under my bed for years and no one’s ever seen it.”

We would spend the next 11 years battling skepticism and technological disasters to bring this hidden film to an audience. But through all the hurdles and setbacks I formed the most unlikely friendship with Didi, as he is known, a man with a large heart living in a small flat crammed with filmmaking paraphernalia. I had the opportunity to hear his remarkable journey and make sense of what makes a person hide their greatest achievement under their bed and refer to it as their “never-born child.”

Didi, whose full name is Thái Thúc Hoàng Điệp, was born to make films. It was in his blood. His father, Thái Thúc Nha, was considered a pioneer in Southeast Asian film and owned ALPHA Film Studios. A true auteur, he wrote, directed, and produced over 20 successful movies that won prestigious awards from the previous government. He represented not only Vietnam, but the whole of Asia in his role as the President of the Asian Federation of Motion Pictures.

Didi was drawn into his father’s world of film. Nha taught Didi the mechanics of the craft and the industry, with intentions of handing him the reins of the studio so he could become an influential filmmaker. He was destined for the international stage.

At just age 20, and with the American War raging, Didi was entrusted with directing his first film, the big-budget feature The Green Age. He navigated strict production timelines while moving a large cast around Vietnam during a full-scale war.

The poster for The Green Age.

In a time when most Vietnamese films were made about war, The Green Age (Tuổi Dại) centers on a love triangle, set against the backdrop of explicit drug use, casual sex, abortions and suicide, drawing heavily on western culture. Competing film studios caught wind of the story and worried its scheduled release at the lucrative end of December might detract from their box office takings. Agents infiltrated the crew and used delaying tactics to slow down production. Film disappeared, equipment was destroyed: “It was like being in a James Bond film,” Didi recalls.

With combat closing in on Saigon, filming wrapped and Didi worked day and night on post-production. He completed the edit and sent the film to Hong Kong to be developed. Days later, he was conscripted into the military to make films. His first job was to work on Unforgettable Lesson, which tells the bitter tale of a man who is stripped of his wealth, pride and freedom and is coerced to work for those he despises.

Didi scrambled enough money together to pay a smuggler to get him out of Vietnam. In the dead of night, he boarded a leaking boat with his wife and young child with the promise of a “new life in a new place,” in his words. They were caught and imprisoned in a Thai refugee camp. It is not something Didi ever talks about, other than that describing it as a place where “women were dragged away and raped.”

After enduring a three-month nightmare, the family resettled in Australia. With limited English, Didi tried to sell The Green Age to TV channels there, but there was “no audience for it.” He tried every avenue to break into the Australian film industry but was labeled an outsider and told “Vietnamese people don’t make films, they make clothes in factories.”

Didi shot wedding videos, figuring “at least I’m still working in the world of film.” He spent his nights editing people’s happiest day, reflecting on his own life and how different things could have been.

Fast-forward to 1986 and Didi tracked down the address of the Hong Kong studio that developed The Green Age. Amazingly, the reels were still sitting on a shelf. They were happy to hand them over, on the condition he paid the US$24,000 in development costs. Didi was not only broke, but heavily in debt. He begged, borrowed and took out multiple loans and flew to Hong Kong, where he was handed a box of eight reels of technicolor. The “never-born child” was back in his arms.

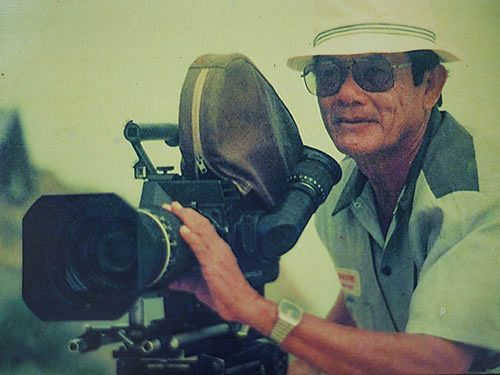

Behind the scenes during the filming of the movie.

Didi immediately called his father, and Nha was so overwhelmed that he was reduced to tears. The film had been saved and would finally find an audience. Two months later, Nha died. Didi's world fell apart, losing his mentor and the closest person in his life. Didi withdrew, the gentle smile that I would get to know and love, disappeared for years. His marriage broke down and ended in divorce.

With no money and large debts, Didi decided to screen The Green Age in Melbourne, capitalizing on the large Vietnamese community in the city. With no money for marketing, he relied solely on word of mouth. Unwittingly, he booked a venue on the biggest shopping sales day of the year. Not a single person showed up. Embarrassed, he vowed to never think or talk about the film again, swearing “I will take it to my grave.”

With his wedding video business waning, Didi was close to becoming homeless. He signed up for unemployment benefits and was sent to my motivational training courses. After his 'film under the bed' revelation, I invited him out to lunch, and a friendship is born.

We are polar opposites but kindred spirits, meeting often, sipping cups of green tea, dissecting love, women and film. Mostly film. I promise him that I will get The Green Age out of his box and onto the screen.

My first hurdle was raising the considerable funds needed to digitize the old film reels. I approached funding organizations, philanthropists, investors, anyone with deep pockets. Years of rejection pass until the money was found. When I break the great news to Didi there was a long, heavy silence. Letting go of his film was even harder than holding on.

Didi’s heart raced as he stood at the production company’s counter, clutching his dusty box. Like a parent being separated from their child for the first time, his grip was tight, his stomach heavy. Back home, that void beneath his mattress felt as empty as his heart. He often called the production company and asked, “how’s my film…is everything ok?”

The digitization job was supposed to take three weeks but drags on for months when a machine broke and needs to be repaired in America. Our excitement at finally receiving the digitized DVD was replaced with despair: the quality was shockingly bad and Didi must painstakingly fix the color on every single frame using free editing software that regularly crashed.

Didi eventually found a job as a repairman. During the day he brought life back to broken machines, and at night he breathed life back into his film. We spoke regularly; he was completely exhausted, but there was something I’d never heard in his voice before, a real passion and excitement; the filmmaker was reborn.

Didi arrived at my house clutching a DVD embossed with The Green Age. I had expected him to burst through the door, buzzing with excitement, but he was more like an UberEATS delivery man dropping off a pizza. He’d reached the end of a long road and was ready to let go.

The film is dramatic, funny and shocking. It captures a period in Vietnam that has been forgotten, perhaps unknown. Shot in color, there are rare images of Saigon before it was changed by war. Far beyond the narrative, The Green Age is an important historical and cultural document.

We decided to rent a theater and stage our grand premier. COVID-19 had other plans. Always maintaining his beautiful outlook on life, Didi smiled and says, “that’s ok, I’m going to show it in the biggest theater in the world."

He posted it on YouTube.

It was not quite the red carpet I had envisaged, but his never-born child entered the world. Actors from the film, now elderly and scattered around the world, finally saw themselves on the screen. Yes, a computer screen, but the magnificent screen.

I was sipping tea with Didi when I asked if he still thought about how different his life may have been. With a wry smile he told me, “I probably would have been as famous as Spielberg, but it’s better it didn’t work out like that.” When I asked him why, he said, “Too much women and drinking, I’d be dead already”.

Finishing his tea, he took a moment and added, “You know I’m the right age.” For what? “To make my second film; directors are at their best when they are over 60.”

The Green Age is available in Didi's original vision, with English subtitles, here.