In 2005, I was in middle school. I had never had a cellphone nor known what the internet was — our home didn’t have ADSL until ninth grade. Life as a fledgling pupil in Saigon revolved around homework, catching the latest That’s So Raven episode on Disney Channel, and riding behind my dad’s back on our family motorbike every day to and from school. But something was about to change: 2005 was the year I went to the movies for the very first time.

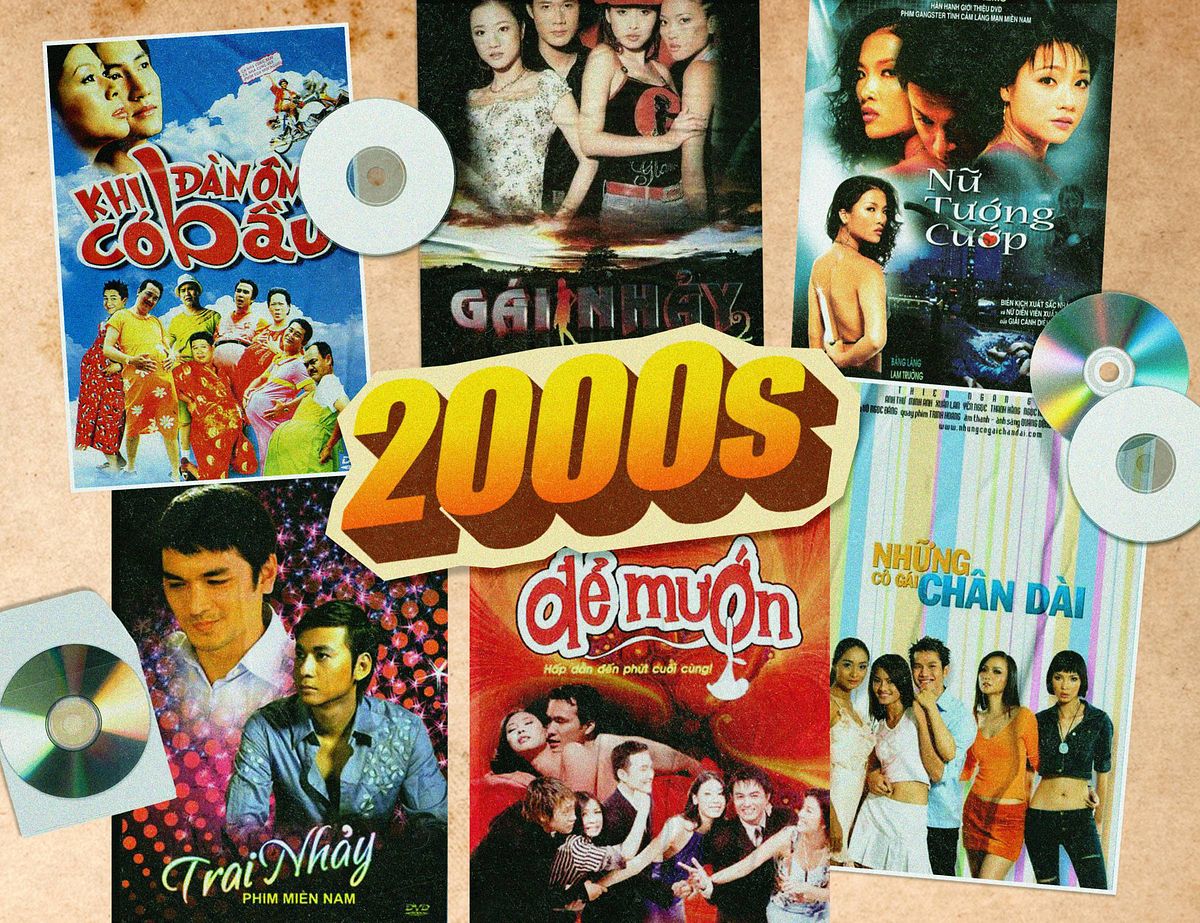

I could have altered the narrative and lied that the first movie I saw was 1735 Km — wouldn’t it be poetic? I could have waxed lyrical about how a little-known indie flick opened my eyes to the world of passionate movie-making. Alas, my gateway introduction into the magical landscape of in-person cinema was a gratuitous Tết comedy called Khi Đàn Ông Có Bầu (When Men Get Pregnant). When you’re a tag-along appendage to your family’s movie nights, there’s little you could do about what to watch, so my cineplex cherry was popped to the raucous humdrum of crude reproductive-themed vaudeville.

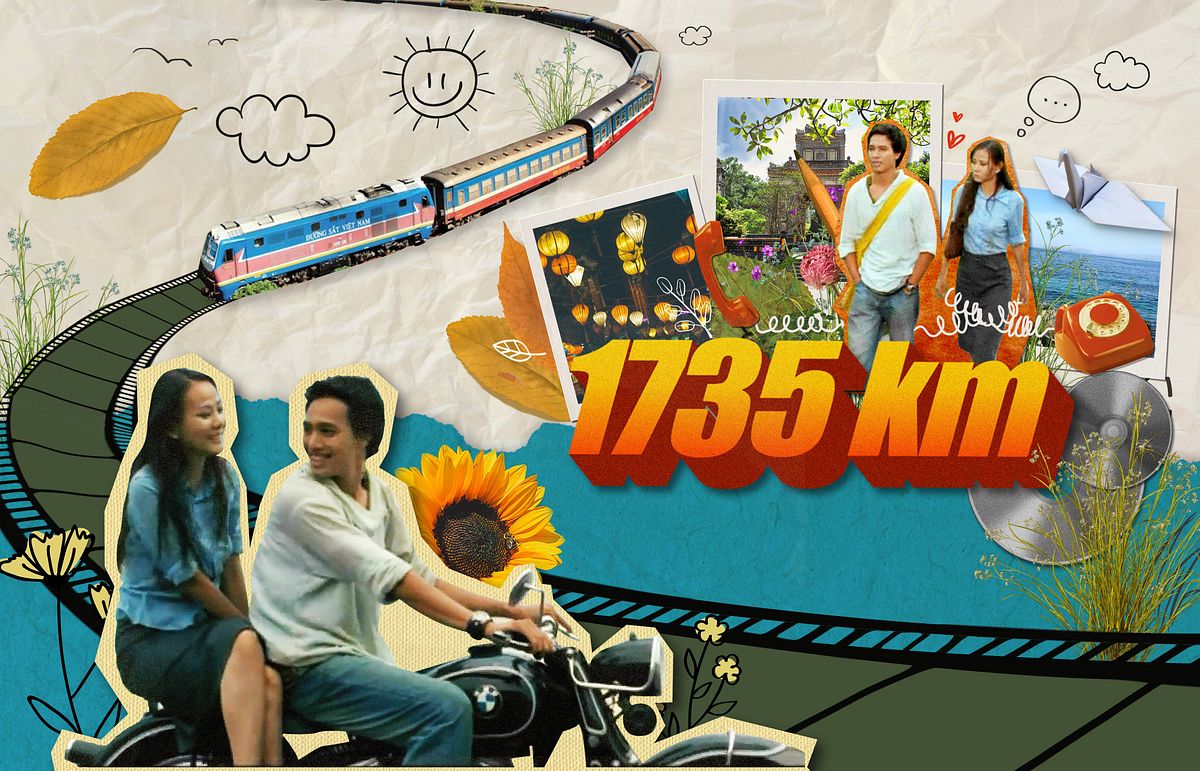

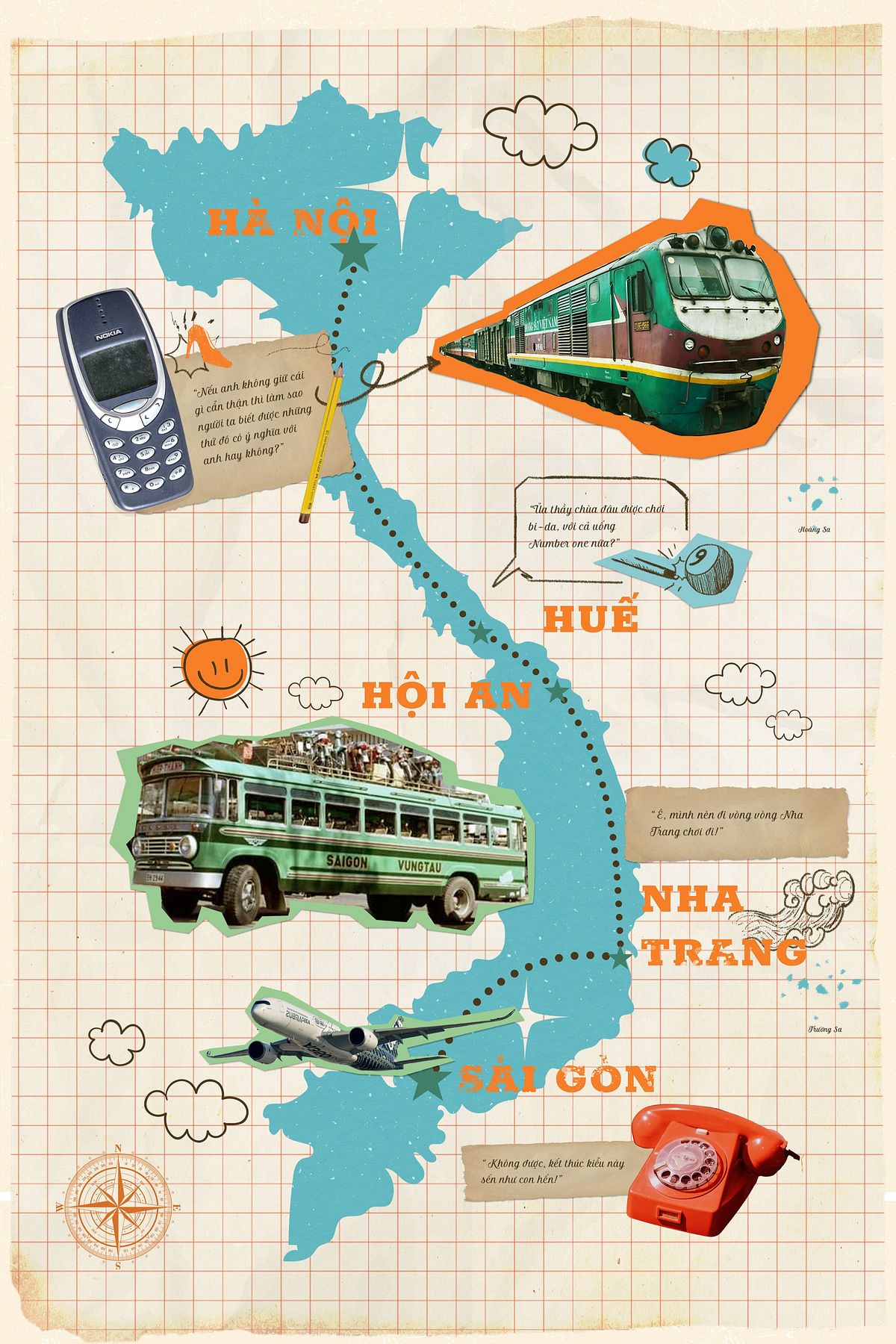

It was in February, and I often think back to that moment, wondering if I had waited eight more months, would I have caught 1735 Km while it was still in theaters? Probably not, because I had no disposable income to my name and a road trip rom-com starring unknown actors wouldn’t be on a young teen’s radar. Obviously, the makers of 1735 Km preferred a less on-the-nose approach to title-crafting than When Men Get Pregnant, but the enigmatic number didn’t exactly rouse interest. The name alludes to the entire length of the North-South Railway from Hanoi to Saigon, a nod to the journey the protagonists go through for most of the film. There wasn’t any magic behind how I chanced upon the film in 2020, 15 years after its premiere: it was recommended by YouTube during lockdown, and I watched it. The magic, however, happened after.

The movie is a romantic comedy in the most literal sense, featuring trope-tastic shenanigans, toilet mishaps, lingering glances, musical montages, and love declarations. At kilometer zero, we meet Trâm Anh (Dương Yến Ngọc) and Kiên (Khánh Trình) as they are settling into their seats before the train leaves Hanoi for Saigon. Trâm Anh is a type-A banker who’s heading south to her Việt Kiều fiancé to meet his parents for the first time. Donning a pencil skirt and fast-talking on the phone in the introduction, Trâm Anh exudes no-nonsense assertiveness. She has goals, a travel checklist, and appears to not care for moony-eyed daydreaming. Kiên is an artistic free-spirit, the antithesis of Trâm Anh. He wears a loose-fitting tunic and carries a yellow bag filled with sketches. He studies architecture but has never been able to commit to a career, so he wanders where his passion takes him.

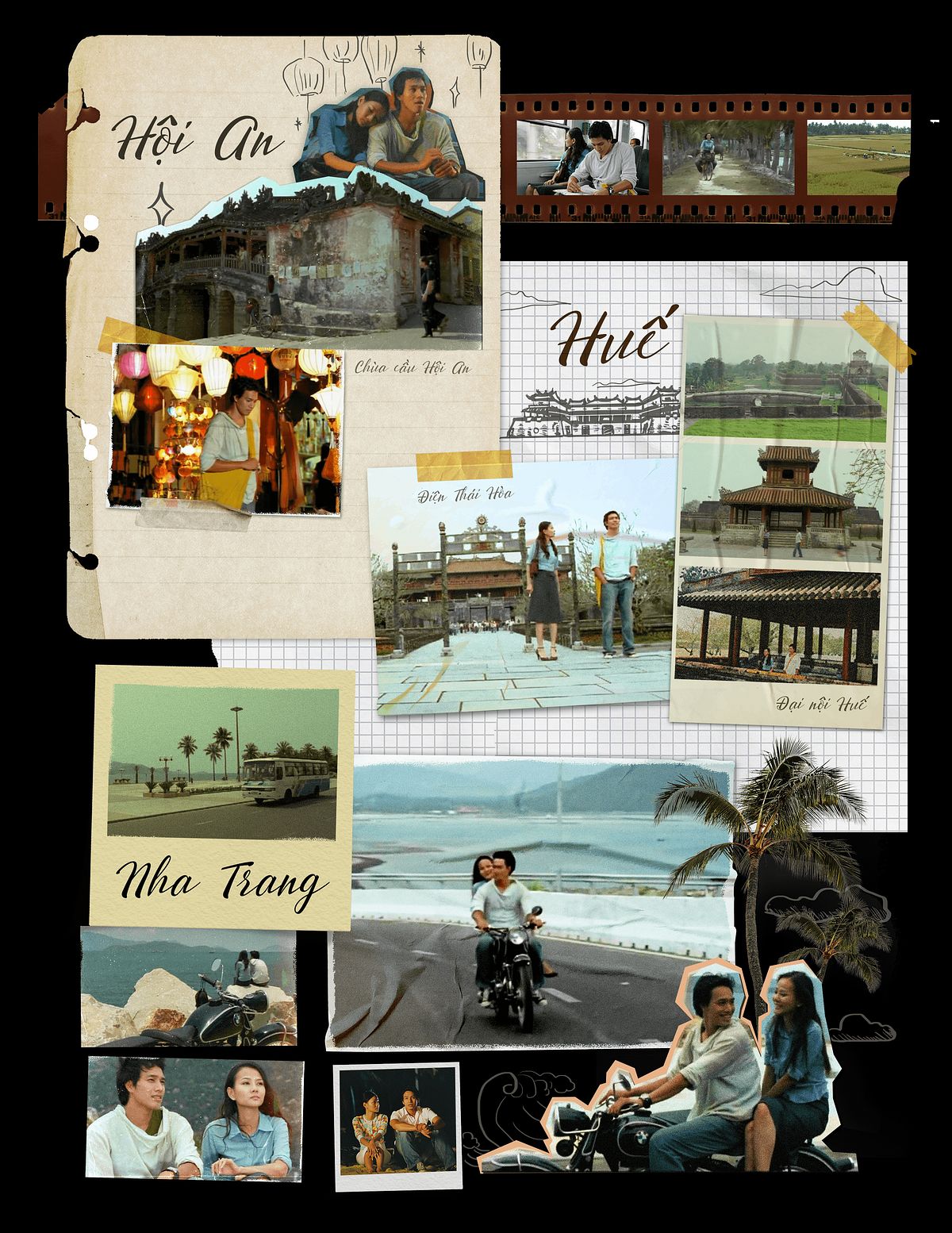

For the first half of the movie, as the train click-clacks its way to Huế, their ideals clash often during passing conversations. He scrunches up imperfect sketches and throws them out of the window; she disapproves. “If you don’t keep things safe, how will others know how much they mean to you?” she laments. “That’s okay. What matters is that I draw,” he appeases her. The script, penned by Kay Nguyễn, sounds stilted here and there, as if it was translated from English, but it is filled with sharp one-liners like this. A bodily function detour causes the couple to miss their train in Huế, and from then on, the road trip side of the film kicks into full gear as they hitchhike to Hội An, Nha Trang, and eventually arrive in Saigon. In true “opposites attract” fashion, they form an intimate connection, though could a few short, albeit memorable, days on the road together build enough momentum to knock our couple off their destined life trajectories? Well, you’ll have to see it to find out.

A movie of firsts

I meet Kay Nguyễn, the co-writer and then main scriptwriter behind 1735 Km, at a hẻm coffee shop that neither of us has been to before. Kay is now something of a household name in the contemporary cinema scene in Vietnam, having written, produced, and directed dozens of films. One of her most high-profile projects is Cô Ba Sài Gòn, a vintage-themed time-traveling story that caused a mild retro fever when it came out in 2017. She turns up wearing all black and a pair of sleek writerly glasses; had we not spoken before through Facebook messages, I would have found her intimidating, purely because of her decorated oeuvre. Any veteran has to start somewhere as a newbie, and Kay Nguyễn’s first-ever script was 1735 Km.

Photo via IMDB.

“Cost me too much therapy money on that movie lol,” she jokingly quips when I first reach out to her seeking more information on the film. In 2004, Kay was a 19-year-old arts student at Grinnell College in the US, studying art history and theory to become a curator or an auctioneer. She started writing about cinema for a website, because a friend was dating its webmaster and they desperately needed content. For a while, discussing and reviewing films turned into an enjoyable side project, until one day, a message arrived from Vietnam presenting a strange opportunity to write a script.

It was a member of the production crew for 1735 Km, and soon after, Kay took a gap year to return to Vietnam because “this is obviously more exciting right,” dedicating a whole summer writing and wearing as many hats as she could during the pre-production process because of the limited budget. Another writer was involved in the beginning but soon dropped out, and Kay worked closely with director Nguyễn Nghiêm Đặng Tuấn in pre-production stages, from traversing the length of Vietnam to scout scenic locations to working with the art department to create props.

The crew hit the road in March 2004. For all scenes inside the train carriage, everyone traveled alongside the characters on a three-car train: one locomotive and two wagons, one serving as the set and one as the makeup trailer, costume closet, staff nap room, canteen, and any other function one can think of. The train careened between Saigon, Nha Trang and Hanoi four times because Tuấn wanted the scenery to look right. 1735 Km had a small team, so crew members often doubled as extras — Kay “starred” as a train passenger and even the director himself played Hùng King in a fantasy sequence set in Huế.

Kay wasn’t the only crew member whose first career milestone was 1735 Km. It was also Tuấn’s first feature after graduating from the California Institute of the Arts. At the time, Dương Yến Ngọc, who plays Trâm Anh, was arguably the team’s most famous member. Ngọc had a small but well-received supporting role as a sassy fashion model in Vũ Ngọc Đãng’s pulpy blockbuster Những Cô Gái Chân Dài, released in the summer of 2004. Trâm Anh was her first main role, right off from the optimistic reviews of Chân Dài. Her on-screen paramour, Khánh Trình, mostly modeled prior to being cast as the ruggedly charming Kiên. On the technical side, the rom-com was the first movie of the now highly sought-after K’Linh in the director of photography role.

Charmingly offbeat and earnest

What the production of 1735 Km lacked in resources and experience, they made up for in passion and a youthful drive to prove themselves. To be completely honest, the resulting film is rough around the edges. One of its shortcomings is that it can’t quite decide what it wants to be. It is at times painfully, but earnestly, cheesy, but while you’re busy grimacing at the wooden acting, it throws in an eccentric encounter and you’re once again hooked. There are moments when the logic behind Trâm Anh and Kiên’s course of actions is shaky. But in spite of the flaws, there is an overarching touch of stalwart idealism and innocence that anchors 1735 Km’s emotional core, something that’s getting rarer to come by these days, and was non-existent among the film’s mainstream contemporaries back then — certainly not in When Men Get Pregnant.

In one of the movie’s most tender moments, Trâm Anh and Kiên walk shoulder-by-shoulder along Trần Phú Street in Hội An, surrounded by a kaleidoscope of lit lanterns. Kiên stops their conversation short, craning his neck to marvel at the old textures of the ancient town. Trâm Anh is, by her nature, unimpressed, though only at first. “But we can still see it by looking straight along the street, can’t we?” she queries. “Usually the ground-floor facades are altered too much by cafes and shops, only the upper floors still retain the original architecture of the historic town,” he explains. The camera pans upwards, sweeping past rows of rustic yellow balconies in contrast with a mesmerizing blue of the Hội An twilight. A contemplative score hums softly in the background.

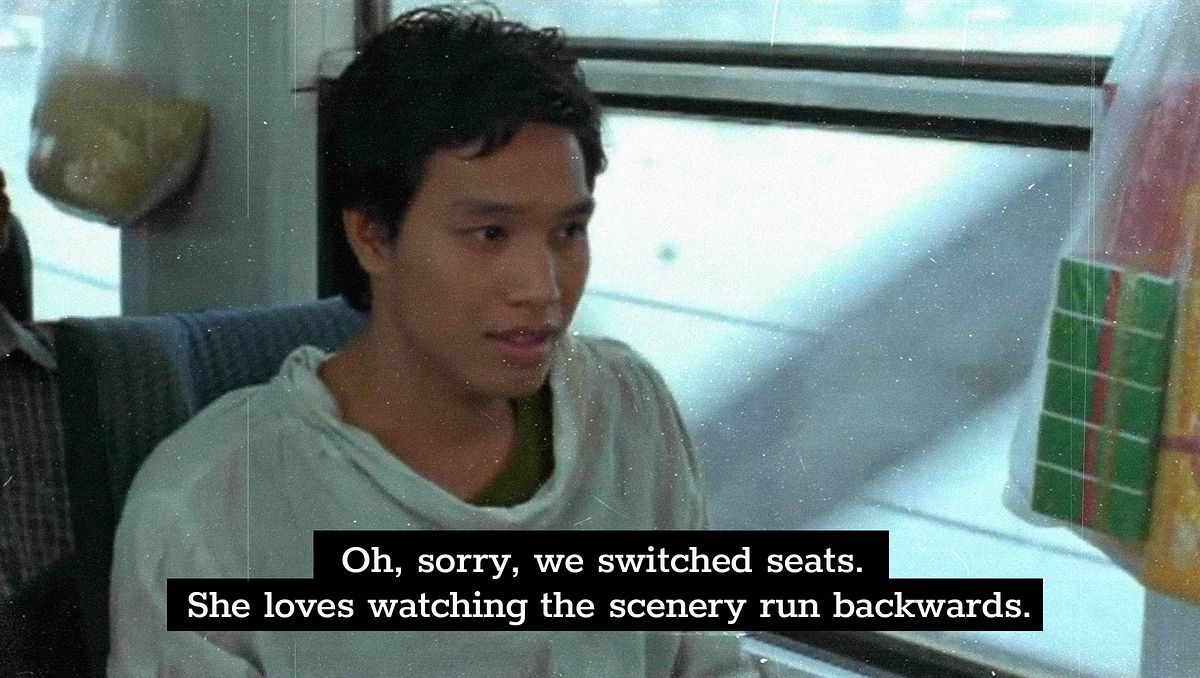

Today, that sequence would likely be dismissed by critics as a schmaltz-fest, but I eat this up, so kudos to Tuấn. It’s a defining moment for their relationship dynamic and, by extension, the movie. It’s from this point that the pragmatic heart inside Trâm Anh starts melting as she begins to see the world from his perspective, quite literally. For once, Trâm Anh the neurotic itinerary planner discovers that there’s more to a journey than how to get from point A to point B the fastest, and there’s unexpected elegance in dilly-dallying. The moment speaks to 1735 Km’s resolute commitment to idealism and sanguine trust in the good-natured core of our interpersonal relationships, one of the things about the movie that endears me to it. Wouldn’t the world be a better place if we spent our time appreciating run-down buildings instead of meeting arranged-marriage fiancés?

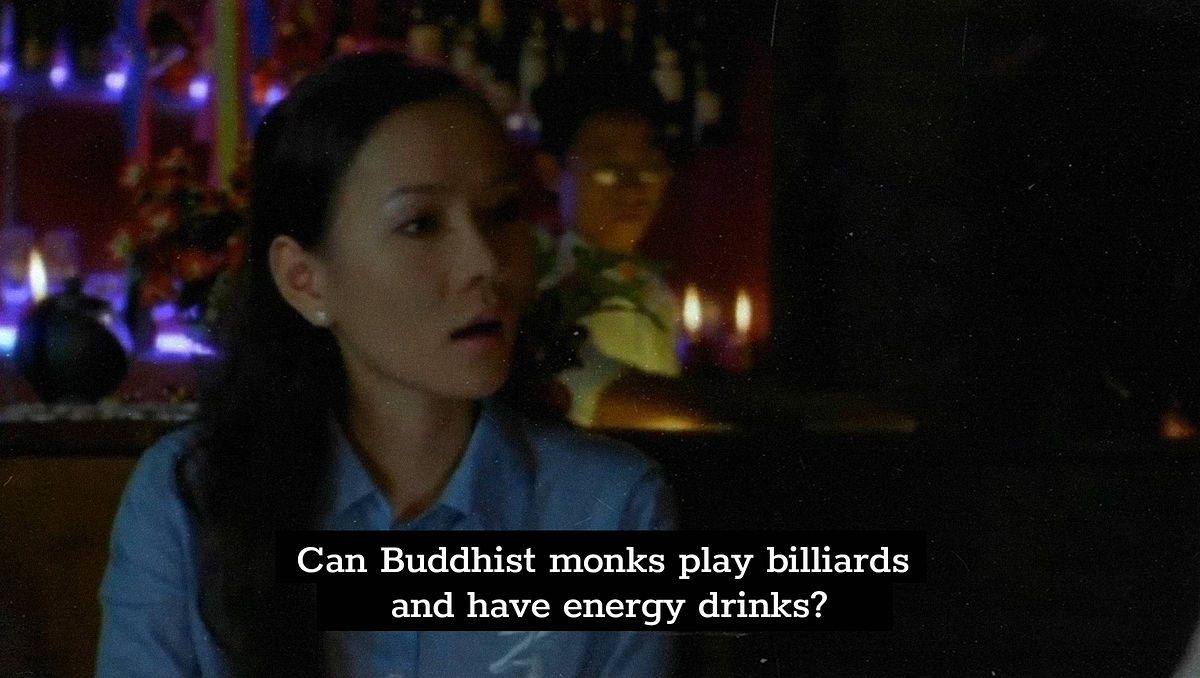

For every moment of earnest philosophy in the movie, there’s a beatnik beat right after to keep your heart from softening too much. These could be anything from encountering apprentice monks playing pool in a dive bar to my favorite side “character” in the entire film, a groupie van filled with Japanese fans of Lam Trường. Waking up in Huế after missing their train, Trâm Anh and Kiên decide to tour the Imperial Palace, and find themselves hitchhiking to Hội An on a minivan chock-full of karaoke-singing, pink-shirted Lam Trường worshippers.

Kay says that the crew wanted to “make it extremely cheesy in a nod to pop culture,” and I think they succeeded — even though they couldn’t have known at the time — in creating one of the most intoxicatingly 2000s moments in cinematic history, all encapsulated in a small Toyota plastered from bottom to ceiling with photos of Lam Trường, his 2004 hit ‘Katy Katy’ blasting in from the car radio. Trường rose to fame in 1998 with the pop powerhouse ‘Tình Thôi Xót Xa’ (the crew tried to obtain rights to air this, but couldn’t, and had to settle for ‘Katy Katy’), and peaked in the mid-2000s. He emigrated to the US towards the end of the decade and disappeared from showbiz by the time the 2010s rolled around, so listening to the tune again unravels vivid memories one could only attain from living through that short era of his stardom.

Passion is a potent fuel, but is it always enough?

When Kay Nguyễn was brought on board, 1735 Km was nothing but a sliver of an idea: in their marketing vision, the producers wanted to create a tourism movie. The romantic connection drives the narrative, but playing background to that will-they-won’t-they is the picturesque, diverse, enthralling landscapes of Vietnam that unravel as the characters travel from north to south on the railway.

The movie was not expected to rake in piles of cash, due to the tiny size of Vietnam’s cinema market at the time. Major chains like CGV or BHD were non-existent; the whole country had some 10–20 cineplexes, and the general public was just getting their head around the concept of watching a film on the big screen, let alone embracing lofty ideals we proudly brandish today like “supporting local features.” “They knew they wouldn’t be able to recoup the money, but they went ahead and did it anyway,” Kay says. “Because they were passionate about it. We were all passionate about it.”

Photo via IMDB

They know they wouldn't be able to recoup the money, but they went ahead and did it anyway. Because they were passionate about it. We were all passionate about it.

1735 Km was a failure. Financially? Sad, but wasn’t unexpected. But nobody expected the general audience to collectively roll their eyes and grimace in confusion. “The box office was not that much already, but we were expected to at least have people call it cool or something,” she recalls. “The thing that hurt was the audience’s reaction. Everyone in Vietnam at that time was like ‘huh’? They didn’t understand [it]. It was hurtful.”

The overall consensus, both in the media and among movie-goers, was that the film was too weird, and the acting performances of Dương Yến Ngọc and Khánh Trình were panned, erasing any previous goodwill the former had amassed after Những Cô Gái Chân Dài. Since then, she has largely disappeared from cinema and only had small roles in TV projects. Trình got married in 2007 and has shied away from the limelight as he embraces a career in entrepreneurship.

The most prominent silver lining after the film came out was probably K’Linh’s career. Most viewers might not be able to appreciate the movie’s peculiarities, but everyone noticed how the camera did its job of capturing Vietnam’s quirks and charms with aplomb. His portfolio now lists a wide array of film projects, from indie flicks to blockbusters, and he frequently cites 1735 Km in interviews as the turning point of his professional life.

On Kay’s part, the critical and financial failure of the movie didn’t deter her from the movie business altogether, as we all know now. If anything, the journey of making it reaffirmed her interest in cinema. “Without that movie, I think I would not have gone into films. I would still engage in some creative businesses because it’s my thing, maybe a novelist or a journalist,” she contemplates. “Whatever that writes and pays the bills. This one was the threshold.”

When I ask if there are things she would like to change about 1735 Km, she answers without hesitating: “If you asked me one or two years right after finishing the movie, I would give your a list of things I would like to change, but it’s been 20 years and I’m older now. I have more perspective. I actually cherish every moment of it, like the little mistakes. They were out of innocence, out of love. So no.”

If you asked me one or two years right after finishing the movie, I would give your a list of things I would like to change, but it’s been 20 years and I’m older now. I have more perspective. I actually cherish every moment of it, like the little mistakes. They were out of innocence, out of love. So no.

Right production, wrong time

For what’s worth, I think 1735 Km holds up extremely well for its age — we wouldn’t be here if I didn't. Its downfall might be attributed to having the misfortune of being born in the wrong era.

Two years before 1735 Km, in 2003, Gái Nhảy (Go-Go Girls) by Lê Hoàng hit theaters in Vietnam. It earned VND12 billion nationwide, a meager figure by today’s standards, but was an unprecedented commercial success for the nascent cinema scene, which until that point was filled with state-sponsored films. These traditional features are not always bad, despite common beliefs, though most would agree that their subject matter tends to err on the solemn side, a quality that might get them made, but not necessarily watched.

Enter Gái Nhảy. With its skimpy jorts, reckless gyrating and excessive body glitter, the film had everything that its genteel predecessors avoided. Curious crowds hit cineplexes for the first time, resulting in astronomical commercial success and ushered in a new era for the local cinema industry, which was learning for the first time that there could be an industry.

Riding the coattails of the success of Gái Nhảy, local studios at the time churned out a smorgasbord of pulpy movies, each more scandalous than the next. These include Những Cô Gái Chân Dài (Long-Legged Ladies, 2004), Lọ Lem Hè Phố (Sidewalk Cinderella, 2004), Khi Đàn Ông Có Bầu (When Men Get Pregnant, 2005), Đẻ Mướn (Surrogacy, 2005) and Trai Nhảy (Go-Go Guys, 2007). They each attained varying degrees of financial success and notoriety, but all share a propensity for taboo — even though few treat their taboo subjects with the dignity and nuance they deserve. Studios learned quickly that sex sells, and that the audience is easy, so the sex, or evocations of sex, should more than suffice, and the quality is optional.

In October 2005, 1735 Km premiered with no sex nor big names, smack-dab in the middle of the racy renaissance that undoubtedly resurrected local cinema but also marred its name in the mind of more serious movie-goers, a tarnished image that we’re only starting to shake in the past few years. Humor must be straight-forward and blatant — famous male comics wearing plump prosthetic bellies, for example — so the unorthodox jokes in 1735 Km appeared out of tune and bewildering. Character-driven romance was rare outside of literature and television, where there is more room for the audience to get to know protagonists; the need to entertain and be entertained wasn’t as pressing in those mediums as in 2000s Vietnamese cinema.

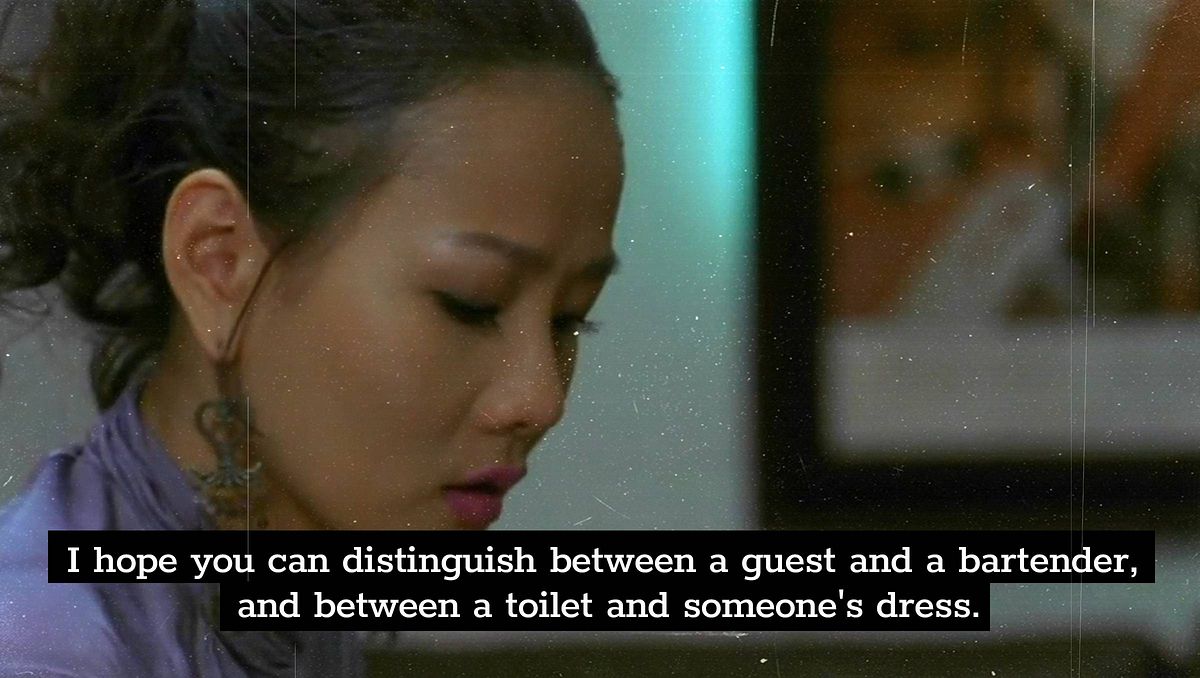

Some of 1735 Km's most wacky lines.

Over time, we have gradually learnt to appreciate movie characters as humanistic reflections of ourselves, worthy of understanding and capable of inspiring contemplation, instead of mere vessels for escapist comedy. Romance movies featuring a pair of complex central protagonists are no longer outliers, but have thrived in recent years, at least critically and in the eyes of a small demographic of fans: Nhắm Mắt Thấy Mùa Hè (Summer in Closed Eyes, 2018), Thưa Mẹ Con Đi (Goodbye Mother, 2019), Trời Sáng Rồi, Ta Ngủ Đi Thôi (Good Morning and Good Night, 2019), and Sài Gòn Trong Cơn Mưa (Saigon in the Rain, 2020) are some standout examples. Most still can't produce the stellar commercial results their predecessors also yearned for, but have amassed a loyal fanbase, something that 1735 Km deserves.

In 2011, BHD Cineplex organized a Vietnamese film festival, screening a host of local features from the previous decade, including 1735 Km, and the reception was reportedly much more optimistic, Kay tells me. It speaks to the film’s enduring charm, something that manages to persist even until 2020. Today, it serves as a visual documentation of 2000s Vietnam, a strange time of paper Vietnam dong bills, cringe-worthy club fashion, and no motorbike helmet mandate. Obsolete setting aside, its central conundrum of whether to stick to a destined path or pursue an exciting new passion is a timeless struggle.

As much as I feel for its financial failure, I am selfishly glad that I missed both screenings in 2005 and 2011, because I wouldn’t have been able to connect to its emotional core or appreciate its vintage appeal then. I have seen 1735 Km five times, including two times as research to write this article. I finished the first watch deciding that I like it despite its imperfections; it was an irrational fondness that I can’t quite explain — there’s just something about it. It was only through sitting down with Kay to reminisce about the 2000s and living vicariously through the stories of her youth spent making this wild project that I managed to piece together what that something is. It’s an embodiment of a time we can’t get back, when it was still okay to make mistakes, to fall in love on a whim, and to take the leap not caring where we will land.

1735 Km is available in full with English subtitles on YouTube. Watch the movie here.