It’s undeniable that Mười: The Legend of a Portrait has left a lasting impression in the minds of a generation of Vietnamese, as the first collaboration between Vietnam and South Korea’s cinema industries. Watching this contemporary classic in 2024, however, made me realize that Mười has not aged well.

Excitement in the early days of the Hallyu Wave

Mười was the first-ever horror film I watched in the theater, and the experience was memorable for many reasons. Beside the grown-up excitement of going to the movies alone with my teenage buddies, our encounter with Mười was made even more thrilling by the fact that the movie was NC-16 and we weren’t of age. Oh the simple joys of being young, when eluding the nonchalant eyes of the ticket clerk — who probably wasn’t paid enough to care that we were underaged — could make one feel like such daredevils.

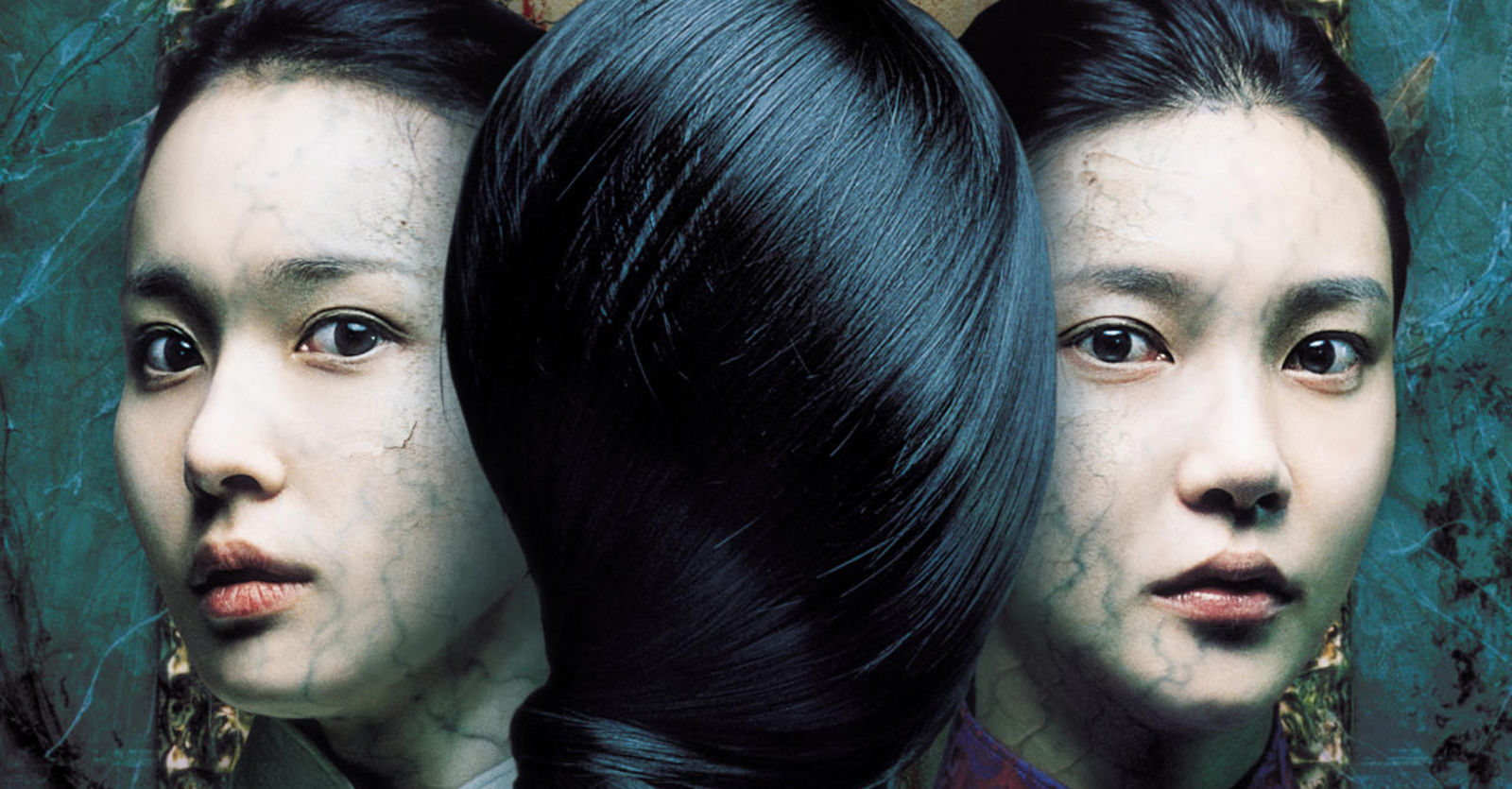

The official poster of Mười.

When Mười was first announced in 2006, it was a project of many firsts, too. Tuổi Trẻ called it “Vietnam’s first commercial film with elements of mystery and horror”; the film was the first Vietnamese release scandalous enough to receive the NC-16 rating, but the media at the time was more celebratory about the fact that it was also the first collaborative release between Vietnamese and South Korean productions. The movie poster, featuring the two Korean leads clad in sleek áo dài, inspired much pride amongst Vietnamese cinema fans, who have long held the belief that our local film industry is well beneath that of Korea.

If the US and the rest of the world are only just getting a taste of the Korean wave in recent years thanks to the bombastic global success of Parasite and Squid Game, Vietnam and much of Southeast Asia fell under the Hallyu spell much earlier than that. The first South Korean drama to ever grace Vietnamese TV screens, Hoa Cúc Vàng (Marigold, 1992), was broadcast in Hanoi in 1996 and then syndicated in Saigon in 1999 to rapturous reception by Vietnamese female viewers. The next decade witnessed a popularity boom of Korean TV series in the country, marked by the release of notable classics like Cảm Xúc (Feelings, 1994), Người Mẫu (Model, 1997), and Bản tình ca mùa đông (Winter Sonata, 2002). This newfound enthusiasm for soap operas ignited a Korean fever that spread to all corners of pop culture in Vietnam, including cuisine, travel, fashion, and later, K-pop.

Mười was co-produced by South Korean mogul CJ Entertainment and Hãng Phim Phước Sang, one of Vietnam’s earliest film companies formed after Đổi Mới. The metaphorical handshake between the two was met with sanguine commentaries in the media; there was hope that it would be a sign of growth for the local cinema industry at the time, which was rife with cheap, raunchy slapstick comedies. In the 2000s, thanks to critically acclaimed titles like A Tale of Two Sisters (dir. Kim Jee-woon, 2003) and The Host (dir. Bong Joon-ho, 2006), South Korean horror became a well-respected brand in Asia, producing high-quality works that were on par with and distinctly different from their Hollywood counterparts. So a Vietnamese co-production with Korea like Mười was seen as a great honor, though the movie ultimately failed to live up to its Korean predecessors.

A Korean horror with Vietnamese set dressing

Mười: The Legend of a Portrait follows the story of two Korean characters, Yoon-hee (Jo An) and Seo-yeon (Cha Ye-ryeon), who were close childhood friends but grew apart as adults. Seo-yeon mysteriously moved to Vietnam shortly after Yoon-hee published her first novel, part of which was based on malicious rumors about her friend. Three years have passed, and Yoon-hee, now facing writing deadlines from her publisher, is enticed by the legend of Mười, a Vietnamese urban legend of a female ghost with demonic powers, and decides to visit Seo-yeon in Vietnam to research Mười for her new book. The long-lost friends meet again when Seo-yeon invites Yoon-hee to stay at her French-built villa in Đà Lạt while she investigates the tale of Mười, but ghastly truths start to rear their heads as Yoon-hee gradually discovers that her childhood buddy is much more involved in the legend of Mười than she first appears.

Cha Ye-ryeon (left) as Seo-yeon and Jo An (right) as Yoon-hee.

The contemporary timeline is interspersed with sepia-tinted flashbacks recounting the life and gruesome death of Mười (Anh Thư), a young girl living 100 years ago. Mười was the tenth and youngest child in a poor family in the Mekong Delta. She fell in love with Nguyễn (Bình Minh), a local painter, not knowing he was already married to Hồng (Hồng Ánh), an aristocratic lady with a sadistic jealous streak. Enraged to discover the tryst, Hồng and her henchmen broke into Mười’s house, tortured her, broke her foot, and obliterated her face with acid. Pushed to a dead-end, Mười committed suicide, but her forever-disturbed soul started possessing an unfinished portrait Nguyễn was painting of her, wreaking havoc on Hồng’s life. Under the pretense of rekindling their love and completing the artwork, Nguyễn lured Mười’s phantom to a pagoda. After he was done with her portrait, a group of monks appeared, using Buddhist chants to subdue her in time for the head monk to lock her soul into the portrait using a hairpin.

Bình Minh (left) as Nguyễn and Anh Thư (right) as Mười.

For the most part, as a horror film, Mười is a decent watch, albeit a formulaic and predictable one. Its simplistic tropes surrounding a love triangle and demonic possession make it easy to digest even for non-horror fans, and its straightforward script leaves little room for plot holes to spoil the fun. Cha Ye-ryeon as the willowy and enigmatic Seo-yeon is the single bright spot in the film, acting-wise, balancing vulnerability and eeriness with surgical precision. You can’t help but sympathize with her tragic life, even though a small part in the back of your mind is ever creeped out by her wide-set grin.

The demon that's sidelined in her own film

The word “collaboration” often implies a somewhat equal relationship between involved parties, but in the case of Mười: The Legend of a Portrait, the Korean end of the equation completely dominated the movie, while the Vietnamese facets were haphazardly done at best and sidelined at worst. For one, the script makes little effort to get the background historical and geographical details right.

Even the gorgeously shot Vietnamese settings are riddled with logistical inaccuracies: the two Korean friends meet at Tân Sơn Nhất Airport in Saigon, drive to Seo-yeon’s Đà Lạt villa, and, in the next scene, are sitting on a boat on the way to visit Mười’s homestead in the Mekong Delta, which is somehow still very well-preserved for a thatched hut that was constructed 100 years ago.

This riverine scenic landscape must be a new tourist attraction in Đà Lạt.

The worst thing about Mười is that I can count on one hand the number of sentences each Vietnamese cast member is given. Even as the titular character, Mười doesn’t have a single line of dialogue, save for the screaming when she is tortured, and the demonic shrieks when she apparates to do the haunting. What’s more, every Vietnamese character is depicted in a bad light: Mười is a demon, Nguyễn is a cheating fuccboi, Hồng is a jealous sadist, even the random old lady on the street is a creep with a white eye. The only helpful character outside the main pair is half-Vietnamese, half-Korean, played by a Korean actress. Maybe the real horror of Mười is how this purported Vietnam-Korea co-production has repeatedly failed its Vietnamese cast and setting.

Hồng Ánh was completely wasted as Hồng. Still, even with the scant material she was given, Ánh's facial muscles did a sterling job.

In every piece of promotional material and throughout the film, Anh Thư wears a white áo dài, accentuating the striking contrast between Mười’s lived innocence and her bloodthirsty, mangled demonic form. Nguyễn, her painter lover; and Hồng, his vindictive wife, are also portrayed in different cuts of áo dài. The timeline puts Mười’s birth year at around the 1900s, making this liberal usage of áo dài impossible, because the first áo dài wasn’t even invented until 1934, let alone the form-fitting, high school uniform-style version Mười is always seen in.

Mười is so ahead of her time that she wears a contemporary dress 100 years her junior.

This historical error is even more grating to notice, considering áo dài is the only key element tethering the film to Vietnam, because there is nothing in Mười that’s inherently linked to Vietnamese culture. The central conflict revolves around a jealous crime of passion so generic one can switch out Đà Lạt with Chiang Mai or Kaohsiung, and áo dài with Thai pha sin or Taiwanese qipao to produce other Asian iterations, i.e. สิบ or 十.

Áo dài is used throughout Mười as a poor attempt to emphasize the Vietnamese element.

Nothing is as ostentatiously “Vietnam” as áo dài — perhaps with the exception of a bowl of phở, but it’s much harder to make supposedly Vietnamese characters wear phở — so international productions usually slap an áo dài on their Vietnamese characters, as a lazy shortcut to signify Vietnam-ness, without bothering to research the appropriate contexts when áo dài is worn in Vietnamese culture. Curiously, the 2000s also brought us two other Vietnam-centric Korean TV projects: Cô Dâu Hà Nội (Hanoi Bride, 2005) and Cô Dâu Vàng (The Golden Bride, 2007). Both feature South Korean actresses in Vietnamese roles, wearing áo dài everywhere and speaking gibberish Vietnamese. Ironically, in this era, Mười was the only depiction of a Vietnamese woman in a Korean production that didn’t fall under the stereotype of a foreign bride.

The dynamic between Vietnamese and South Korean media industries is akin to that of an older sibling and their wide-eyed baby sister. One always peeks at the other through the lens of hero worship, trying on their shoes and makeup while they’re not home, hoping to be like them when they grow up. The other thinks the baby sister’s antics are… cute, but almost never taken seriously. The creation of Mười: The Legend of a Portrait epitomizes this skewed relationship, in which one side tries too hard to please, and the other just doesn’t seem to care enough to put in an effort.