Is Chim Lạc based on a real bird?

The specific species that may have inspired the bird that led Vietnam’s ancestors into the Red River Delta 3,000 years ago is a matter of great debate. The animal cast on countless bronze drums as a symbol of how nature provides for Vietnamese prosperity could be a stork. Or a crane. Possibly a hornbill or a heron. Given its elongated beak, it’s probably not a hawk, eagle or other bird of prey. It might even be a now-extinct bird or a mythical creature.

But determining which specific animal may have inspired Chim Lạc is both impossible and unnecessary, especially when taking into account Vietnamese frequently uses the same word for wildly unrelated species such as porcupines and hedgehogs (both nhím) and casual terms can refer to a number of animals regardless of their actual taxonomical relations. Thus con cò can be used for certain types of stork as well as unrelated egrets, herons and even pelicans that are united via several characteristics: light-colored plumage, long sleek legs for stepping through mud and water to hunt for fish and frogs, and long beaks at the ends of slender necks.

Con cò may be one of the first animals a child ever hears of thanks to the popular lullaby

Đậu phải cành mềm lộn cổ xuống ao.

Ông ơi ông vớt tôi nao,

Tôi có lòng nào ông hãy xáo măng.

Có xáo thì xáo nước trong

Đừng xáo nước đục đau lòng cò con.”

A con cò goes to look for fish during the night

Landing on a soft branch, it tumbles down a pond

Mister, could you help to scoop me up

And if I shall betray you, you could cook me

In case you do, please use clean water to cook

Don’t cook me with dirty water, my children would be hurt

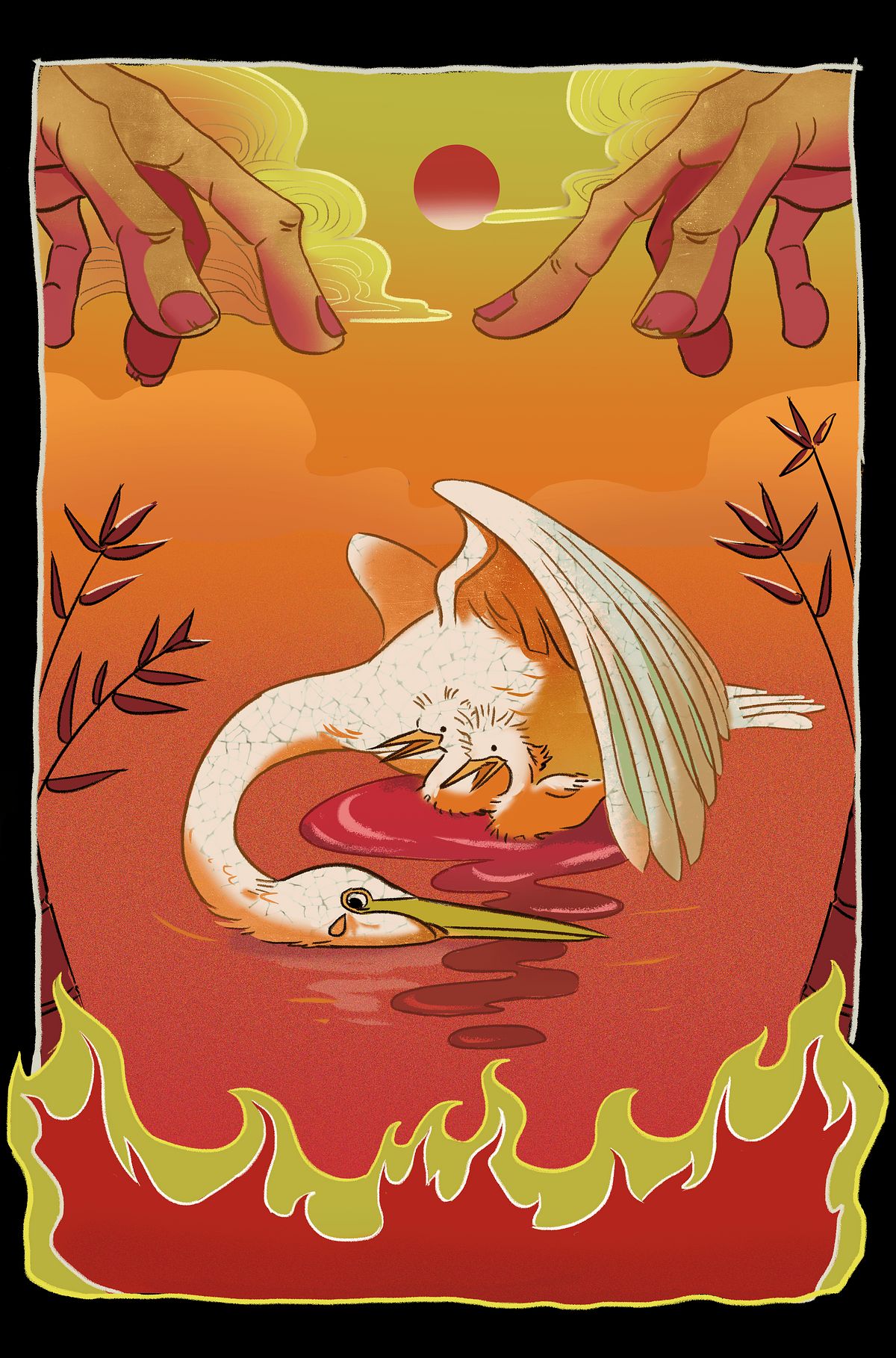

This song, known to all mothers in Vietnam, aligns con cò with poor farmers who may die at the hands of the rich, yet hope their deaths are “clean” after having lived a life free of dirty deeds or treachery.

Vietnamese encounter con cò frequently in assigned folk literature and poems where the bird is associated with hardworking women who toil and sacrifice for their families. Chế Lan Viên wrote a famous poem dedicated to them and they are referenced frequently in Ca Dao pieces: “Con lươn thụt xuống; con cò bay lên” (brother eel dives, mother con cò flies). Vietnamese writers continue to make use of their image, such as Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai who ends a recent poem:

Con cò would be used as a stand-in for female farmers

It is no surprise that con cò would be used as a stand-in for female farmers and an image associated with lives connected to the land, as many of the birds, of which there are numerous species in Vietnam, often hunt, roast and soar beside rural people bending down to tend to their rice.

People outside of Vietnam’s major cities continue to see them on a daily basis and encounter their image on a number of practical items such as the brand logo of a leading fertilizer. Yet, for the country’s urbanized citizens do not interact with them on a daily basis, con cò exist as metaphors for the slower-paced agrarian lifestyle of past generations or idyllic childhoods. In this way they constitute part of the collective identity of Vietnam, as exemplified by the con cò outfit proposed for Miss Vietnam and their appearance on numerous tour companies’ brand logos and use in modern remixed songs.

But for all that can be represented by con cò, it is difficult to speak too specifically of their behavior as the term refers to different species with different traits. The Little Egret (Egretta garzetta), an archetypal interpretation of the term, is a small and graceful bird whose feathered neck curves into a slender S when flying while the Greater Adjutant (a type of stork), known as the “prodigy of ugliness” has a featherless head that sits at the end of an outstretched neck, pointed like a compass tip when in flight.

If we consider con cò not as a specific species but a metaphor, they can represent mankind’s abuses of and efforts to protect nature. Poachers hunt them for meat while farmers construct habitats to keep them safe. Meanwhile, humans have greatly altered their diets and disrupted their flight patterns. In some drastic instances, available garbage entices them to not migrate with devastating effects on their reproductive cycles. Further, the use of pesticides in addition to deforestation to make way for farmland has reduced the number of storks around the world.

Throughout Vietnam, there are several popular con cò islands that draw visitors from the city. Important elements of Vietnam’s efforts to preserve ecosystems, the coastal forests allow guests to reconnect with nature and a lifestyle where humans interacted more closely with the land. One may never be able to look into the sky and see a chim lạc in flight, but a trip to one of those protected spaces or a journey to the countryside will certainly offer up an image of a con cò easing across the horizon. It is not hard to imagine one’s ancestors seeing the same and following it in search of new land to settle. Perhaps, considering con cò will inspire people today to do the same. If you decide to abandon your stressful city life in search of a more peaceful existence in the countryside, you can explain it simply - “I was following con cò.”

Video Đảo cò chi lăng via Halovietnam.vn

Collages by Phan Nhi, Jessie Trần, Lê Quan Thuận, Phương Phan

Illustrations by Hannah Hoàng

Animation by Phan Nhi and Hannah Hoàng.