Disney’s Aladdin, Super Nintendo, digital fingerprint technology: the outside world was familiar with all these by 1992. Sao la, however, remained unknown.

If you are in your 30s or older, there was a time when more people in this world knew of your existence than one of Vietnam’s most unique and scientifically valuable creatures. The sao la is truly one of the most astounding natural discoveries in the last 50 years, as people believed all the world’s large land animals had already been discovered.

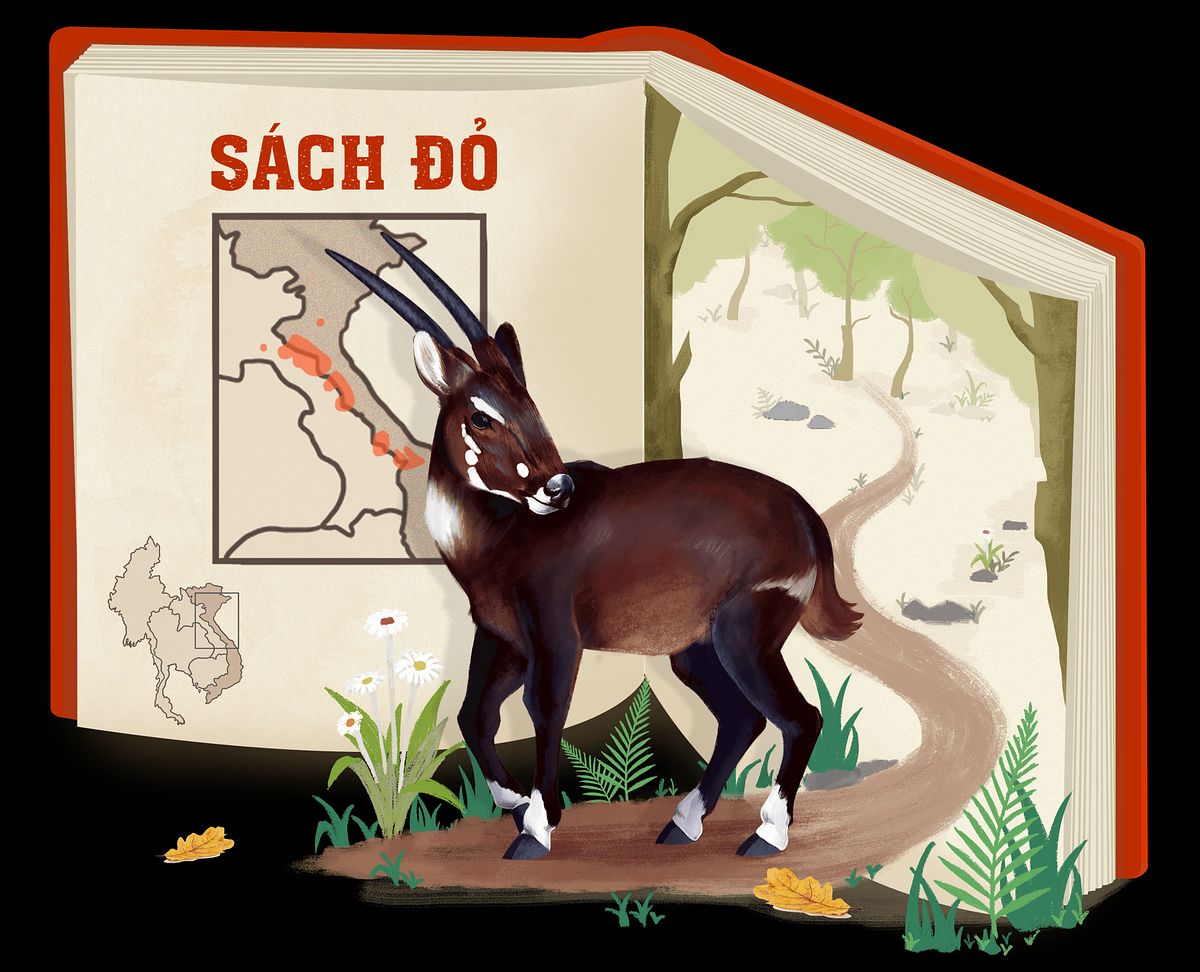

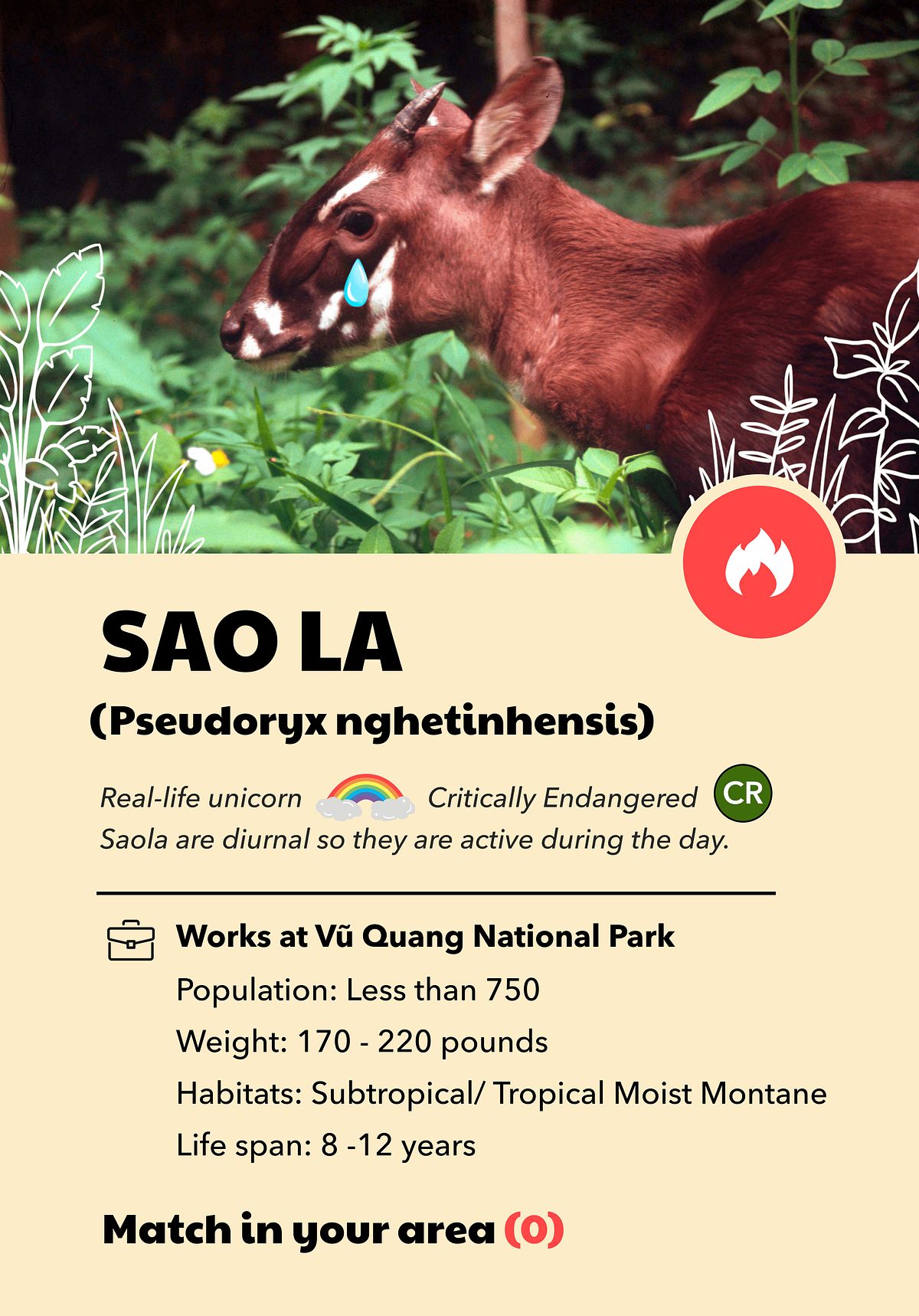

Weighing up to 100 kilograms and standing at 84 centimeters tall with spectacular 50-centimeter horns worn by both males and females, sao la (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) is neither small nor forgettable. So how was it that no scientist in the world knew about it until less than three decades ago?

So how was it that no scientist in the world knew about them until less than three decades ago?

In 1992, the head of a wildlife research expedition in the Truong Son Mountains conducted by Vietnam’s Ministry of Forestry (now part of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development) and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) noticed a very strange skull on the wall of a hunter in a remote village. Almost instantly, the expert recognized it as an unknown species. For all their virtues, amateur zoology is not a common habit of rural villagers. So while locals admitted to seeing the animal on rare occasions, and even hunting it, they could not offer anything of significant scientific value. And they were also of little help in helping anyone find it.

It took four years until a zoologist, William Robichaud, actually came across a live sao la that was penned up by some villagers in Laos along the Vietnamese border. Even though it died shortly after, he was able to study it for several days, adding much to what we know of the animal, including that, while it resembles an antelope, it is actually much more closely related to buffalo and cattle.

In the years since, several more sao la have been captured, though they sadly do not live long in such conditions. Anecdotal tales from people living in the remote mountains between Laos and Vietnam, a few telltale signs of them foraging, and a few photos from camera traps are the only proof we have of sao la in the last decade. Critically endangered, it is believed that there are fewer than several hundred sao la in the wild.

As they are critically endangered, it is believed that there are fewer than several hundred sao la in the wild.

Originally given the name “Vu Quang ox,” science changed its mind, as it’s wont to do, and settled on sao la, the name used by the Tai ethnic people in the area and villagers in neighboring Laos. The sound of the word seems the perfect description for such an elusive creature: slipping in like soft hooves hardly perceptible on the forest floor and ending in an echo, a manifestation of something known but not seen. The reality is less poetic, however. Sao la are the tapered posts that support a spool winding thread used by people in the area that resemble the animal’s horns.

As he observed it, Roibchaud was amazed by the creature’s peaceful nature and its willingness to eat directly from his hand. But most notably, when seen from the side, their horns merge into one. Hence its nickname: “Asian Unicorn.”

When seen from the side, their horns merge into one. Hence the nickname: "Asian Unicorn."

Unicorns are, of course, not real. While the Vietnamese mythological kỳ lân is translated as unicorn, it is rarely depicted with the long singular horn that western versions describe the creature as having. That and kỳ lân’s origins in Chinese mythology make sao la an unlikely relative. And while it would be nice to imagine the concept of unicorns in Europe resulting from a time when sao la roamed the wilds of Asia and rumors of their gentle nature and gorgeous horns spread across the world via trade routes, it is believed that most of Europe’s concepts of unicorn exist thanks to rhinos, as well as narwhal tusks harvested in icy northern seas.

The word unicorn, however, has taken on a metaphorical meaning in common speech that seems to fit sao la. The rarity of sao la, the improbability of its discovery, and the attention it has received in the conservation community all make it quite a remarkable creature fitting of the term.

Books have been written about the search for sao la; there is a national Sao La Day; entire conservation groups were started to protect them; it was considered for the official mascot of the 2021 SEA Games; and Google even released a 3D version of the creature for use in augmented reality. Such attention is rarely granted to other endangered species, making the Vietnamese forest bovine a unicorn in that sense. Unfortunately, they will need all the help they can get. Poaching is the greatest risk, despite them not even being the aim of illegal hunters, but rather they get caught in traps set for animals with more value in the traditional medicine trade. Of course, deforestation remains a threat to any animal living in remote areas.

Poaching is the greatest risk, despite them not even being the aim of illegal hunters

Despite sao la’s popularity, because of their rarity and the remote areas they live in, we know infinitely more about most things in this world than we do about sao la. From the love lives of K-pop idols to the complexities of space travel, significant knowledge and awareness exist for relatively recent phenomena compared to a creature that has roamed the planet with us since the Ice Age. Hopefully, this “Asian unicorn” will not slip away before we can learn more about it. Its loss would be a haunting reminder that the world is getting smaller by the day, and not for the better.

Collages by Hannah Hoàng, Phan Nhi, Phương Phan, Jessie Trần.

Illustrations by Phan Nhi and Patty Yang.