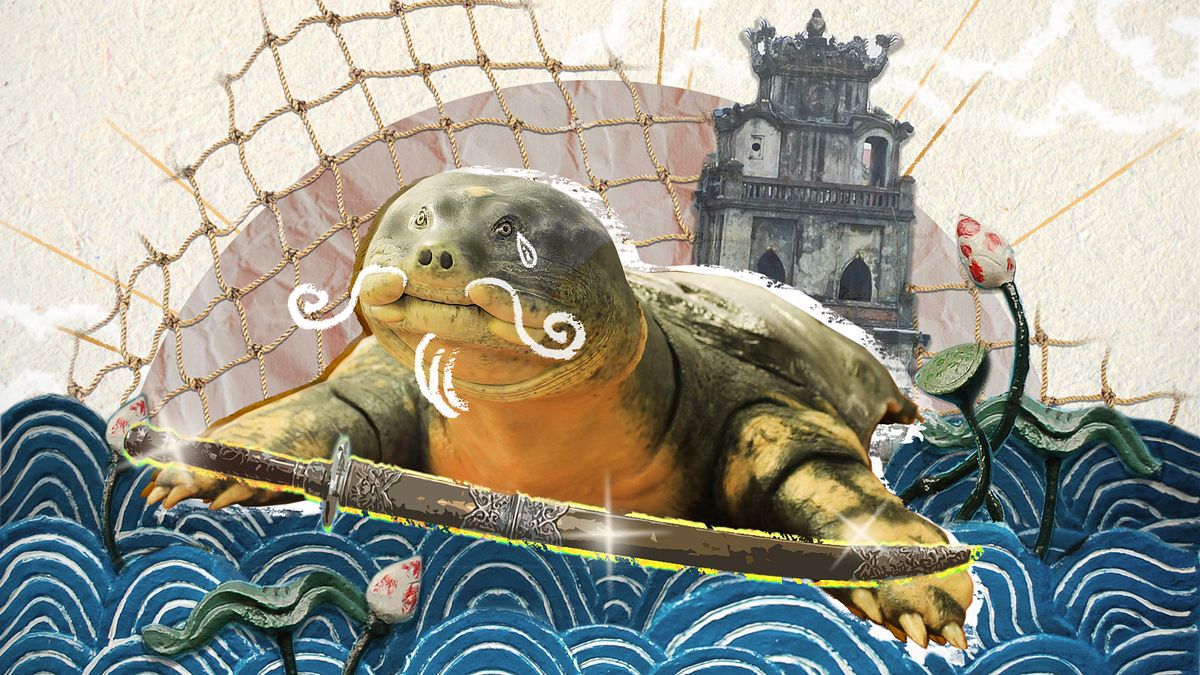

Everyone knows the mythological story of the Hoàn Kiếm turtle.

In the 15th century, Lê Lợi received a golden sword from the turtle god, Kim Quy, so he could vanquish occupying Chinese forces and later returned it to the lake. The tale demands no further attention — it's mentioned on placards surrounding Hồ Gươm, referenced in tourism material and alluded to by keychains, figurines and other tchotchkes depicting blades balanced on turtlebacks. The legend is, of course, associated with a real creature, however, and if one drags it from the murky myths swirling around it, they’ll discover some ugly truths.

Let’s start with what species the creature exactly is. On June 2, 1967, a local fisherman was tasked with safely netting a turtle that had emerged from the lake so it could be understood. He bashed its skull in with a crowbar, instead. When the reptile died from its injuries, its 200-kilogram body was preserved and kept in the lake’s island-situated temple and now looms in the background of countless photos of people dressed up for weekend joy jaunts. The massive turtle was recognized as a representative of a large softshell turtle species found in swamps, lakes and rivers in northern Vietnam. In the early 1990s, biologist Hà Đình Đức introduced it in several unpublished scientific papers and newspapers articles, using different names before finally settling on Rafetus leloii, in homage to the legend surrounding it. Of course, locals never used this scientific name, preferring to refer to the individual in Hồ Gươm as Cụ Rùa, which often led to the incorrect assumption that it was male.

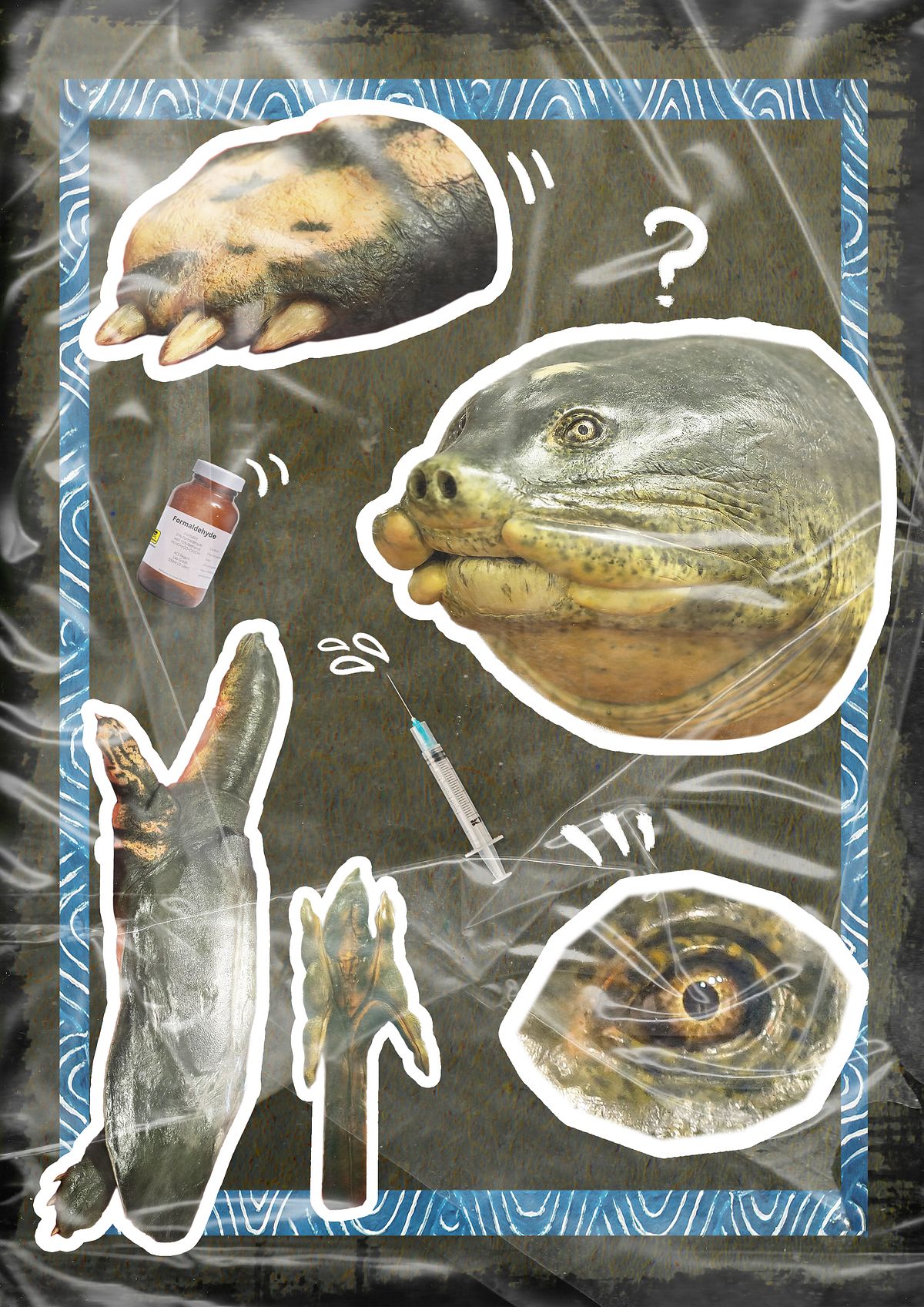

Yangtze giant softshell turtle. Photo via Asian Species Action Partnership.

Few things are sexier than a scientific nomenclature debate, and that is precisely what went down as the Hoàn Kiếm turtle attracted more attention, domestically and internationally, in the 21st century. There were only two or three species known in Vietnam at the time and scientists around the world concerned with its fate began to wonder if it was truly a unique species or was instead a Rafetus swinhoei, or Yangtze giant softshell turtle, known in southern China and teetering on the brink of extinction. Đức and some of his colleagues remained firm in their assertions that it was a unique species based on some questionable observational details. They argued that the Vietnamese individuals should therefore not be considered viable for breeding programs with their Chinese counterparts. More recent genetic tests contributed to a general consensus that the world’s three officially recorded, living individuals as of 2023 — one each in China’s Suzhou Zoo, Vietnam’s Xuân Khanh Lake and Đồng Mô Lake — are all Rafetus swinhoei.

But let’s now put aside the matter of names after acknowledging how absurd it is that the world’s largest freshwater turtle that dwells exclusively in Asia is named after Robert Swinhoe, a British naturalist who aided colonial forces in their oppression of China during the Opium War. Unlike the depictions of the legend, anyone who has seen photos of the Hoàn Kiếm turtle must admit that it’s a repugnant reptile: flaccid appendages tipped with off-kilter claws, beady eyes and a fat, wrinkly neck leading to a head that resembles a deflated party balloon resting shriveled on the floor three days after a birthday celebration no one attended, not even the birthday boy's own mother. When soaked in formaldehyde, pumped with resin and stored in a display case it would make for a regal footstool, but seen in its natural environment, it’s frankly rather grotesque.

One could rightly expect that the Hoàn Kiếm turtle would fall victim to the “Bambi syndrome” wherein humans only care about preservation efforts focused on animals deemed “cute” (think pandas, elephants and snow leopards). However, the endangered reptile has actually received significant private and public funding aimed at its conservation including a recent VND1 billion donated by the Danko Group to the Asian Turtle Program (ATP) and conservation groups are ramping up their collaborative efforts. It has also garnered unprecedented press attention for a reptile. A lengthy New York Times write-up of the 2016 death of the turtle in Hoàn Kiếm described it as “a mythic symbol of Vietnamese independence and longevity” and it “would be difficult to overstate Cu Rua’s spiritual and cultural significance.” No doubt much of its domestic prestige is connected to Vietnam’s four mythic gods, only one of which has an actual, living corollary.

Even with the attention and funding, conservations have their work cut out for them when it comes to Swinhoe’s softshell turtle. It is certainly possible that a few more individuals exist in remote bodies of water and there is genuine belief amongst scientists that a second one may be lurking in Đồng Mô Lake near Hanoi where a female was caught in 2020. Even if true, that would bring the known number in the wild to three. And up until now all captive breeding programs have proven to be utter failures, with China’s only captive female dying in 2019 while under anesthesia for the artificial insemination procedure. It seems like a lost cause.

One could rightly expect that the Hoàn Kiếm turtle would fall victim to the “Bambi syndrome” wherein humans only care about preservation efforts focused on animals deemed “cute.”

Our story now takes a familiar turn to human’s failed stewardship of the natural world. Elder members of communities outside Hanoi remember times when they would routinely see Swinhoe’s softshell turtle in the wild, although by the 1960s, they were already being hunted as much sought-after meat and later hydroelectric projects drastically altered the environments they thrived in. Finally given official protection in Vietnam in 2013, it seems to be too little too late, considering not long before that “if one was caught, its meat was shared with the whole family, relatives and the neighborhood,” a woman explained to the press, adding that “its eggs were also collected and soaked in salt, as local people believed turtle salted egg helped cure diarrhea.”

So, stripping away the myth and metaphorical value of the turtle and what are we left with? A nondescript creature doomed for extinction thanks to humanity’s greed, violence and ignorance. In light of this reality, I’ve heard an interesting proposal to honor the legacy of the Hoàn Kiếm turtle. Whenever venturing to Hanoi, slip a dead cat into the lake’s filthy waters for its memory. With nods to one of the final recorded viewings of it when it can be seen scarfing down a submerged cat carcass in front of scores of captivated onlookers, it's a crude act symbolically befitting the way we’ve treated them, but one that at least takes into account what they would actually have enjoyed. And maybe it's time we consider what they would like, for once.