I was a teenage cliché. No matter how much I try to rack my brain to find any other personal connection to the incandescently red tree that is phượng vĩ, I keep going back to my middle school crush and that one tree in the front yard of our school.

Phượng vĩ is the Vietnamese name for Delonix regia, also known as royal poinciana, flamboyant tree or flame tree in English. These names are no doubt inspired by the tree’s uniquely vivid flowers that can light up an entire neighborhood when they bloom. Nothing can signal the passage of time quite as dramatically as phượng does. Every year, from April to June, poincianas across the country erupt in joyful parades of fiery blossoms and cicada symphonies, letting you know that summer has arrived. For school children, this often dovetails with the end of a school year and, if you’re part of the graduating class, time to say goodbye to a chapter of yourself you never thought you would miss. Generations of Vietnamese students have grown up bidding farewell to their formative years with the tint of phượng flowers coloring their most sentimental memories, so phượng has earned a deep-rooted reputation as the symbol of summer, school years, and teenage dreams.

A road in Hậu Giang sandwiched in between rows of phượng trees. Photo by Lý Anh Lam Photography.

For a plant with so much cultural significance in the country, it might be unbelievable to learn that phượng vĩ didn’t originate from Vietnam or even the continent of Asia. But such is the intricate, complex relationship between mankind and nature. Plants, birds, critters, and mushrooms have few thoughts for our arbitrary national borders and would flourish with reckless abandon wherever they feel most nourished. Like lêkima and dragonfruit, which were brought to Vietnam from South America, phượng vĩ is native to Madagascar Island in Africa, but our climate proved hospitable enough for them to take root, prosper, and enchant us into propagating them everywhere.

How phượng vĩ infiltrated our schools

Scarlet flowers light up a road in Nha Trang. Photo by Flickr user Khánh Hmoong.

Historical records point to the French colonial government as the reason behind this botanical migration. In his book Hà Nội còn một chút này, essayist Nguyễn Ngọc Tiến details how the deciduous African tree became a fixture in public schools in the capital. A year after Hanoi was subjugated by the French, in 1889, the colonial administration established a botanical garden in the northern area of the town near today’s Hồ Tây. The garden served two purposes: first, to cultivate a range of vegetables familiar to the French palate but didn’t exist in Vietnam at the time, like lettuce, carrot, kohlrabi, and cauliflower; and second, to be a botanical playground of sort to test out various species of ornamental trees to plant across the city’s public spaces, parks, and government buildings.

Each phượng blossom has four red petals and one variegated petal. Photo by Rohit Tandon on Unsplash.

The push for diversity in tree-planting was meant to ensure trees would shed their leaves during different seasons, reducing the workload of maintenance workers and ensuring local streets would stay luxuriant year-round. Phượng vĩ, palm and African mahogany (xà cừ) arrived in Hanoi from Africa, alongside senna alata (muồng) from South America, and ylang ylang (hoàng lan) from Malaysia. Phượng vĩ quickly caught the eyes of the then-government for many reasons. It grows fast. Its canopy spreads widely instead of tall. Instead of broad, paddle-like leaves, phượng branches are peppered with rows of tiny compound leaves like verdant teeth of giant combs, making them less likely to clog up the sewage system. And, of course, who can resist the allure of those gorgeous scarlet petals?

Generations of Vietnamese have grown up with phượng flowers, so it has earned a deep-rooted reputation as the symbol of summer, school years, and teenage dreams.

Phượng vĩ first appeared on Hanoi streets like rue Paul Bert (now Tràng Tiền) and rue Kô-Ngü (then Cổ Ngư, now Thanh Niên) and by that summer, many French-run schools in Hanoi started planting phượng trees to help provide shade. The southward migration of phượng began a bit later with a decree issued in 1906 by Governor-General Paul Beau to standardize the schooling system, which, until then, was quite messy.

Amongst other operational guidelines, the decree stipulated that school years begin in September and end in May, and that campuses must plant trees for shade. Phượng vĩ had already been sashaying all over schools in town by then, and the new school calendar perfectly timed its most spectacular blossoming with the end of the curriculum, enshrining its status as an emblem of pedagogical farewells. The mayor of Hanoi encouraged new schools to plant it, and as more schools were founded in Central Vietnam, they too adopted the plant in accordance with the decree. By 1912, all 24 of the capital’s private institutions were growing phượng vĩ in their yard.

The cultural significance of phượng vĩ

A "chicken fight" using phượng stamina. Photo via Flickr user Thái Anh Dương.

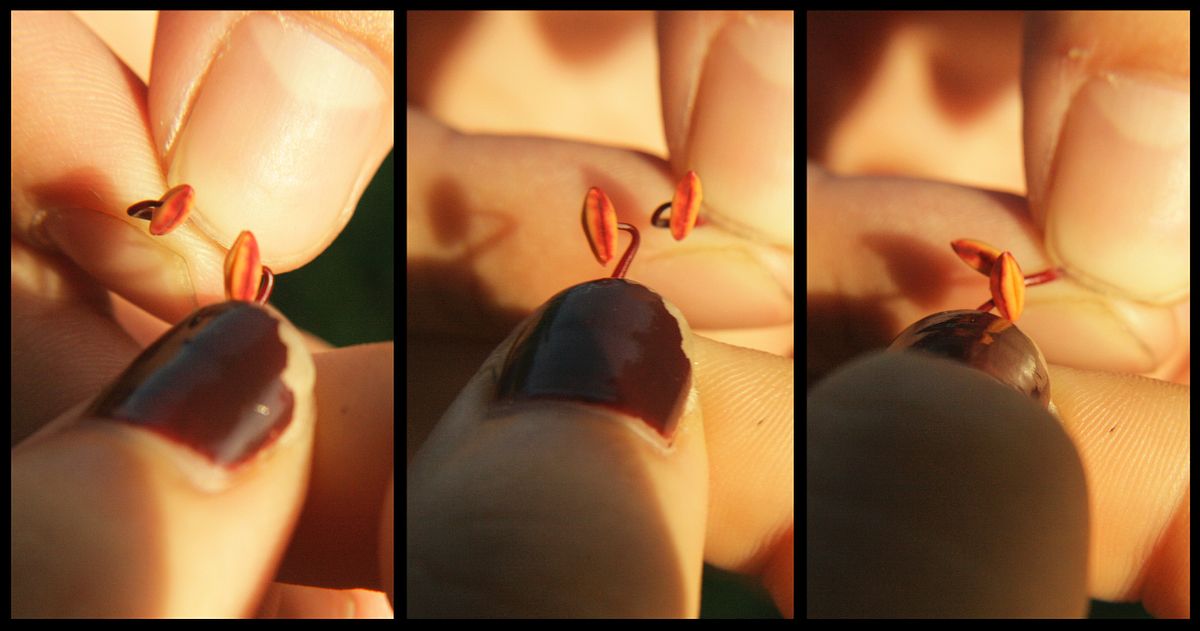

Like many of its predecessors, my secondary school has a phượng tree right in the middle of the front yard, reinforced by a square granite foundation and surrounded by stone benches. Unrelated coexistence is how I would characterize our relationship. Like two untouched Venn circles, we went about our lives separately, until one day, when the circles began to overlap for the first time. Under the canopy of our phượng tree, my school crush showed me how to do “chicken battles” with phượng blossoms. She would find the biggest flower buds, peel off the outer verdant sepal, and pluck out the strongest-looking contenders from the bud’s stamina. Each “chicken” is a strand of stamen with an anther still attached on top and each battle begins by locking the anthers together and then pulling them apart rapidly. Whichever “chicken” is beheaded first loses. I rarely ever think about phượng flowers or my time in secondary school today, but I returned home that day knowing that rare occasion when the Venn circles overlapped would stay with me for a long time.

How to make butterflies from phượng blossoms

For many generations of financially strapped Vietnamese students, crafting butterflies from phượng petals is the best way to craft keepsakes on a budget, as it doesn’t require anything but fallen flowers and nimble fingers. Once completed, the butterflies could straight away be pressed in notebooks and agendas for drying, ready to surprise you decades later when you accidentally flip through the pages just to see them fall out, looking as faded and sepia-tinted as your memory of their creation. Truly a friend of impoverished students, phượng blossoms can also serve as a free ingredient in student meals like gỏi hoa phượng or canh chua hoa phượng thanks to their subtle sourness.

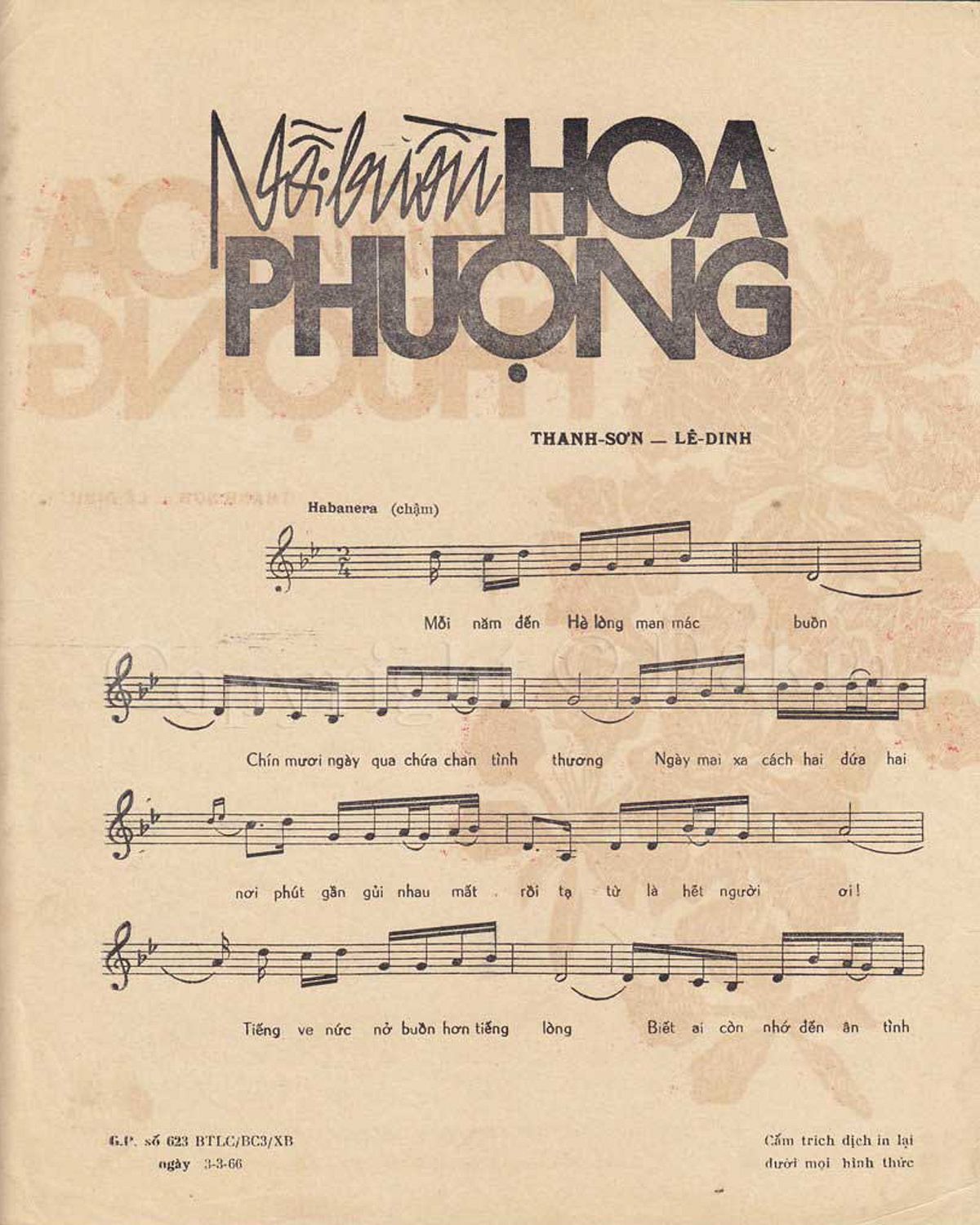

For my part, I am content with my own teenage cliché, a happy memory of phượng and my secondary school crush, but not everyone is as lucky. Composer Thanh Sơn’s story is instead one awash in longing and the ache of missed connections. Sơn grew up in Sóc Trăng in the 1940s in a family of 12 siblings. When he was 13, one of his classmates was a sweet, affable girl named after the scarlet flower: Nguyễn Thị Hoa Phượng. She attended the school after her family moved to town from Saigon for her father’s job as a civil servant.

The music sheet for 'Nỗi Buồn Hoa Phượng,' first released in 1966.

“We were friends for more than a year and got really close,” Sơn shared in an interview. “Suddenly, the next summer, she told me that her family got reassigned to Saigon, so she wanted to meet me to say goodbye.” When he asked for an address so they could keep in touch, Phượng said in tears: “My name is Hoa Phượng. Every year, when summer comes, if you see the flowers bloom, remember me.” They have lost touch since.

In his young adult years, Thanh Sơn moved to Saigon and became a successful composer. In the summer of 1963, seeing phượng blossoms while walking past a schoolyard reminded him of his childhood friend, so he penned a few lines to express how he felt. Those heartfelt words would go on to become the lyrics for ‘Nỗi Buồn Hoa Phượng’ (Hoa Phượng Sorrow), the biggest hit of Thanh Sơn’s music career and phượng’s most prominent cameo in pop culture, one that has endured until today as a timeless bolero classic. While it was first recorded by Thanh Tuyền, today the iconic summer ballad can be heard via the voice of numerous performers and karaoke sessions all over Vietnam.

Thanh Tuyền was the first performer bringing the song to stardom.

The tipping point

By the 2020s, phượng vĩ’s role as a cultural icon, especially in association with students and school nostalgia, might seem unshakeable, but our relationship with the tree was about to change, perhaps for good. It was a typical morning almost exactly three years ago, on May 26, 2020, at Bạch Đằng Secondary School in District 3 of Saigon. The school entrance at 6am was buzzing with purrs of motorbike engines, vendors of morning snacks belting out street calls, and school children roaming about. Gaggles of kids were sitting around the schoolyard’s phượng tree enjoying their breakfast when the tree suddenly toppled over, trapping them beneath its heavy but hollow trunk. In the end, 18 pupils were injured, and one of them, a sixth-grader, didn’t survive the unexpected accident.

It was later discovered that, even though the tree looked healthy and lush from the outside, its trunk was rotting from the inside. The incident is not unheard of either, as phượng trees have fallen down in Huế, Biên Hòa, and Sóc Trăng, sometimes maiming or even killing passersby. A number of botany and urban planning experts have since cautioned against widespread planting of phượng vĩ in civic spaces. Dr. Đặng Văn Hà from the Vietnam National University of Forestry acknowledges its cultural role, but warns against putting it in schools.

Trần Phú Secondary School in Pleiku decided to fence off the tree to prevent future accidents. Photo via Người Lao Động.

According to Hà, it’s fast-growing, but grows into soft branches and trunks that are prone to rotting. Its roots are shallow and fragile, requiring special care to prevent destabilization. It often has a short lifespan and starts deteriorating by the 30-year mark. The way phượng is planted in school yards, caged in by concrete and hampered by a lack of soil, also contributes to the weakening of roots. There are ways to safely grow phượng in school, Hà shares, but administrators must monitor its health closely and prune it properly during rainy seasons.

No matter what, the fallout of the tragedy at Bạch Đằng was swift: across the country, school management boards ordered extensive trimming and axing of phượng vĩ and other heritage trees in fear of another tree-toppling. From a school icon that entered bolero hits and poetry, many phượng trees were reduced to chunks of lumber strewn on concrete. When tragedies strike, it’s often in our nature to start placing blame. As much as I am fond of trees in general, and phượng vĩ in particular, I can’t blame school principals for not taking risks when it comes to the safety of their students, and I can’t blame trees for trying and failing to withstand the tests of time. Again, I find myself at a loss for a satisfying conclusion to this phượng vĩ soliloquy, because of how uncertain everything is. Perhaps this, not teen nostalgia, is the true meaning behind nỗi buồn hoa phượng.