There’s a 99% chance that a Vietnamese child’s first exposure to lá dứa, or pandan, is in the form of rau câu.

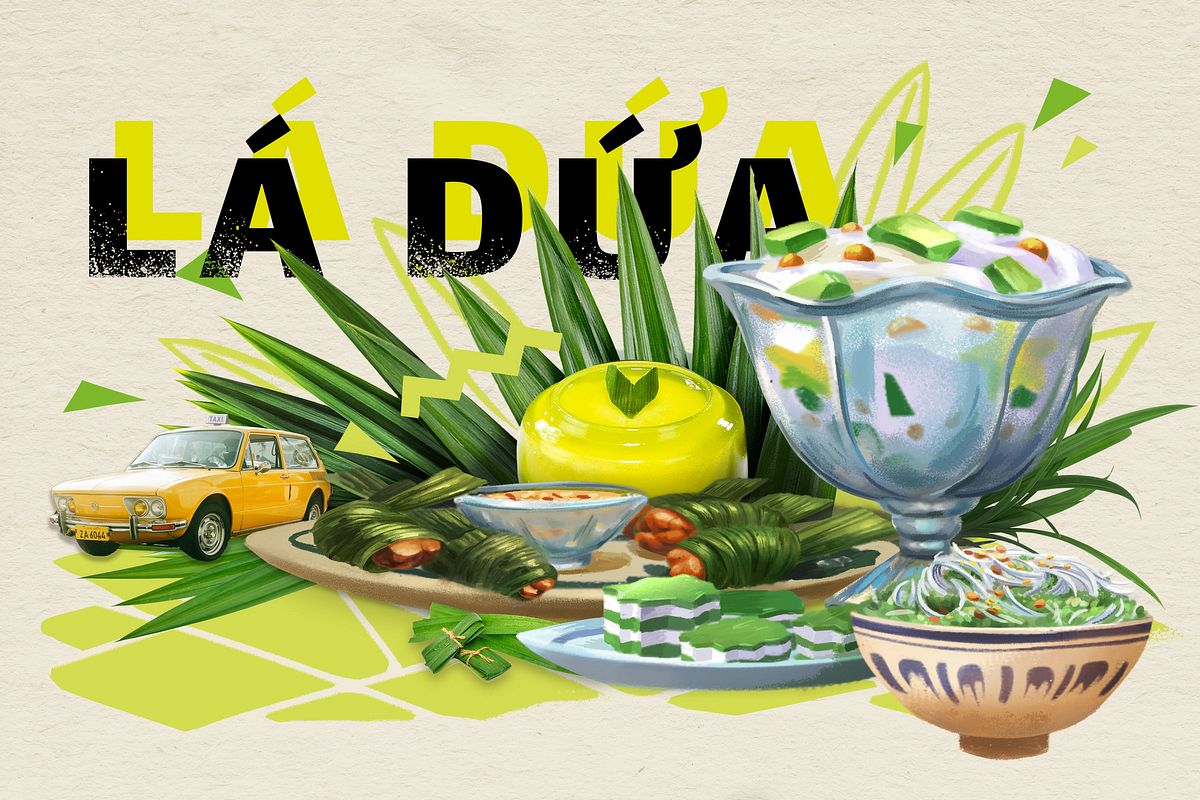

The pavement simmers in the scorching heat of April in Saigon. The vendor opens the fridge and lifts out a tray from rows and rows of petite bowls and cups. Brandishing a tiny knife like a surgeon, she makes a few delicate slices across the smooth surface of the jelly inside. She retrieves a ceramic plate, upturns the tray, and out comes blocks of glistening rau câu in layers of opaque white, brown, and vivid green. She sprinkles a handful of shaved ice on top of the dish, puts three fruit forks on the side and sets the plate down onto the plastic table where you and your two friends squat in awe. For a fleeting ten minutes, the heat of summer seems to have melted away as you munch on the firm, cooling morsels of agar jelly, tasting milky coconut, bitter coffee, and refreshing pandan.

Rau câu is probably the most humble and common way to indulge your pandan craving in Vietnam.

In 2017, British chef and comfort food matriarch Nigella Lawson proclaimed that pandan was going to be “the next matcha,” touting the leaf as the latest trendy flavor to watch. Over the years, international food media has reiterated her sentiment numerous times, though the comparison varies with each tantalizing touting. Saveur calls it “the vanilla of Southeast Asia” while The Guardian dubs it the “new avocado.”

Why can’t pandan just be itself? In efforts to contextualize exotic fares obtained from deep, mystifying corners of Asia to an audience who might otherwise be flabbergasted by them, there’s a tendency among editors to forge snappy parallels of flavors, no matter how contrived and, sometimes, tone-deaf the comparison is. Branding ingredients or dishes with a storied long-enduring role in Asian cultures as cutesy and trendy is reductive and completely discards their paramount importance in their birthplaces’ national history and the people’s collective memory.

Lá dứa (Pandanus amaryllifolius) is native to Southeast Asia and had been a cornerstone of regional cooking and traditional apothecary for centuries before Lawson declared it the next anything. It dyes our rice, seasons our cake, wraps our chicken, soothes our joint pain, and regulates our blood sugar. The earliest mention of Pandanus amaryllifolius in English was by Scottish botanist William Roxburgh in 1832 in his description of a small pandan bush hailing from Amboyna, now part of Maluku Province, Indonesia.

Did you know?

As the only member in its genus with aromatic leaves, the species’ true origin remains a mystery to this day, as there is only one record of a male flowering specimen in western New Guinea, none of a female.

Another enigma is that lá dứa as we know it today seems to be nonexistent in the wild and only thrives in domesticated settings. A dearth of flowers means that most lá dứa bushes and trees are sterile and propagate vegetatively via suckers or cuttings, producing genetically identical pandan babies. In the early 2000s, biochemists managed to identify the chemical compound responsible for pandan’s alluring aroma as 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline, the same substance that gives basmati and jasmine rice their prized scent and the binturong’s uniquely buttery pee smell. If something smells good, does it matter where the smell emanates from?

Unknown origins aside, pandan has shown up in the traditional cuisine of many Southeast Asian countries and as far north as Taiwan and as westward as the Indian subcontinent, though the latter was commonly credited to maritime trading activities between Southeast and South Asia.

Pandan has shown up in the traditional cuisine of many Southeast Asian countries and as far north as Taiwan and as westward as the Indian subcontinent.

In the years I spent toiling away with my studies in Singapore, every time I dug my face deep inside their pandan chiffon cake, I marveled with gratitude at the ancient power of nature that helped distribute lá dứa throughout the region. So that they’re as enamored with the simple emerald leaves as I am, and so I could soothe my pandan craving easily whenever a hankering hits. One staple of Singaporean breakfast food is kaya, a custard rich in both coconut and pandan eaten with freshly toasted bread slices. Just to put it in perspective, someone managed to distill an aroma into an edible, unctuous, creamy paste. Where is their Nobel prize? Many Asian cultures like India and Indonesia use pandan as flavoring bundles in stews and curries, and of course, Thailand’s gai hor bai toey (pandan-wrapped chicken) is a global favorite.

Rau câu is probably the most humble and common way to indulge your pandan craving in Vietnam, but the green leaf and its aroma can be spotted fresh in sticky rice, a plethora of chè, bánh da lợn, or the Mekong Delta special treat bánh ống lá dứa. A more processed version exists in the form of sâm dứa syrup, the star ingredient of sâm dứa sữa, everyone’s favorite after-school drink.

The audiovisual experience of living in Vietnam is a vivifying one, so reminders of home are aplenty. Landing at Tan Son Nhat after a harrowing flight, the first thing I notice is usually the fact that I can now understand ambient murmurs. As I amble outside the terminal, somebody shouts “Đụ má!” and I burst out laughing, thinking “ah yes, the unique Saigon delicacy.” In the taxi, the driver speaks with a southern lilt, but the icing on top is a withering, but still green, bundle of pandan leaves he has placed on his dashboard to perfume the car interior. That’s when it sinks in: I’m really, finally, undeniably home.

Graphics by Hannah Hoàng, Lê Quan Thuận, Patty Yang, Phương Phan, Phan Nhi.

Natural Selection is a series of articles that explores Vietnam’s native flora and fauna. From overlooked plants to iconic critters, Natural Selection aims to highlight the country’s wild and wondrous nature.