The highway eases into sand and gravel the way history descends into myth and legend when traveling towards Long An. A mere 27 kilometers outside of Saigon, the province feels a world away: the difference between a cocktail made with 18-year-old scotch, jackfruit-infused rum, seven types of bitters and brandy-soaked organic cherries and a plastic water bottle of homemade rượu nếp. The latter was the reason we were going there: for information, interviews and anecdotes to complete Saigoneer’s two-part investigation of the history of rice wine.

Google Maps was a horrible guide for our trip. Similarly, unanswered emails, ignored Facebook messages and websites that hadn’t been updated for years meant we were going in fairly blind. We thought we had a general idea of where to find a community still crafting the traditional liquor, but our crew of two staff photographers, one who served as a translator, and a writer, were nervous until we started seeing plastic gasoline jugs prominently displayed on roadsides besides signs boasting rice wine for sale.

Perhaps they were intrigued by the trio who claimed to be journalists; maybe they were surprised that anyone was expressing interest in what they considered a mundane occupation; possibly they just appreciated the company; but, for whatever reason, many of the elderly women milling around their storefronts were eager to invite us inside their homes to talk with us and show us their operations.

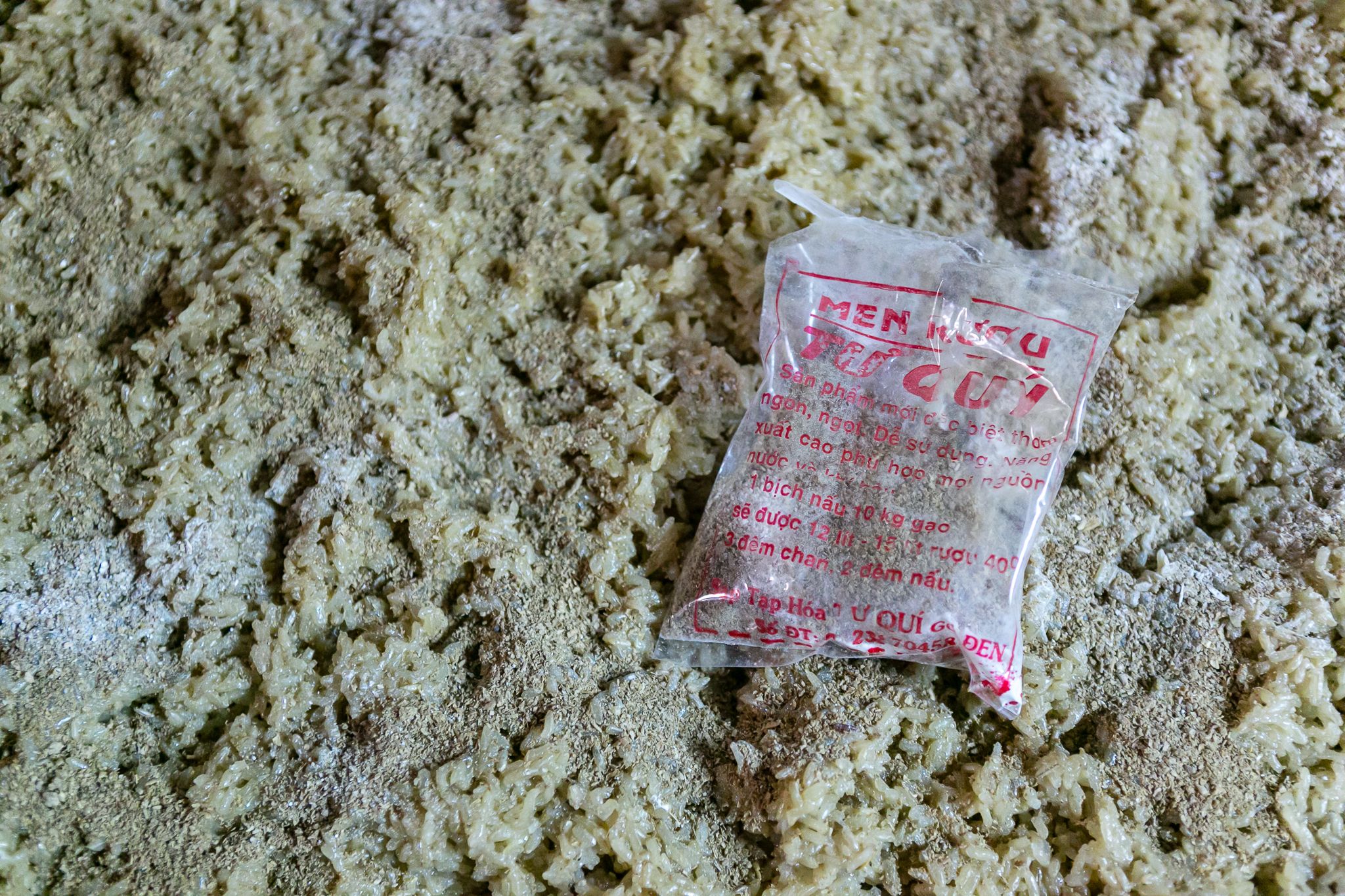

The basics of rice wine production is simple. Rice is boiled until soft, then laid out with a layer of fermentation starter containing yeast and various ingredients sprinkled atop for three days; and, finally kept in big plastic tubs for two weeks before it is distilled — a process that removes the impure elements from the final product.

It's all about rice quality. In the small-batch rice wine business, one’s success depends entirely on reputation, so — beyond not cutting the liquor with harmful chemicals — the right type of rice must be expertly paired with the proper yeast starter. Phan Thi Kim Nguyen, pictured above, explained that in addition to generations of knowledge that contribute to recipes, a good rice wine maker must know how to tailor batches to his or her client. That means understanding what fruits or medicinal herbs, spices or animals a buyer will steep in it. In the latter case it must be 80% alcohol by volume, otherwise, the product hovers around 40%.

Long An is a decidedly rural area; familiar scenes of mud-caked farm and construction equipment and spark-bathed motorbike repair operations and all-purpose building shops fill the small downtown that occupies a stretch of the highway-side storefronts and spills into a wet market. Homes and schools rest behind the commercial area and quickly give way to expansive fields.

After a simple meal of phở at the type of humble spot where a request for beer sends an owner scurrying next door to buy a couple cans, we were off to follow our final rice wine lead of the day.

It’s not easy to secure a Grab driver in Long An; one has to get lucky with a car that has recently dropped off a customer from Saigon. We finally chanced upon one: a Vietnamese descendant of Chinese immigrants who spoke Cantonese and could thus offer his interesting story to our Singaporean photographer. He had recently lost billions of dong in the lumber business and was just working as a ride-share provider to keep his mind off it. He had no problem taking us seemingly into the middle of nowhere and waiting to then take us back to Saigon.

Tucked between rice fields traversed by cows and buffalo was a rather large country-style house that, as we came to learn, was likely built with rice wine money. Rượu Đế Gò Đen, despite what its polished website might suggest, is a very small operation. A multigenerational group of women greeted us at the gate of the home and invited us in to show off their equipment.

A small wood-burning stove fermented the rice wine that was funneled directly into a giant cement basin for collection. Companies from Saigon would occasionally call to collect product which wasn’t paid for by the gallon but rather according to the weight of rice that was used. The woman who explained the process said it was her husband’s company, but they were quarreling and he, therefore, isn’t around to operate it now. It was uncertain if they were planning for him to ever return.

We had caught them at a time when they weren’t making any rice wine (maybe after Tet she said), yet that didn’t stop them from inviting us to try some from their collection. Selecting from a cabinet filled with repurposed bottles of all brand, style and original liquid, we were offered shot glasses of something that went down as smooth as alligator skin and yet had a flavor and charisma that left us longing for more. I asked if she liked to drink rice wine herself and was quickly given a facial expression best described as "does a gecko regrow its tail?"

As we left, we passed near the hẻm that took us to our first stop of the day: the home of a 75-year-old man named Minh. Google had suggested he was one of the premier rice wine producers in the area, a claim to which he admitted. However, long gone were the days of the man that embodied 1970s Saigon cool and cooked up batches of rice wine in his home according to his wife’s family’s recipes: a time period which he proudly showed us a photo of.

Without much regret, he explained that there was no longer money in the trade as a result of competition from producers willing to cut their liquor with dangerous methanol as well as the availability of cheap beer, so he stopped making it. Was he going to take down the prominent rượu nếp sign from the front of his house? Uncertain. Before we could ask, he had ambled off to give his wife a foot massage. It was clear that like many people in Vietnam, rice wine was no longer of any great interest to him.

This article was originally published in 2019.