Cuc Im Lang, the latest exhibition from renowned fashion designer Nguyen Cong Tri, presented ten collections spanning his 20-year career through the lens of ten contemporary artists across different mediums and practices.

The exhibition ran three days, from December 27 to 29, and took viewers through a series of artworks based on ruminations between the fashion designer and the artists in ten connected rooms.

The artists participating in Cuc Im Lang included visual artist Ngo Dinh Bao Chau, contemporary dancer and choreographer Ngo Thanh Phuong, architecture studio VUUV, digital and multimedia artist Lu Yang, visual artist Truong Cong Tung, dancer and choreographer Alexander Tu, photographer Hua Nhu Xuan, Tung Monkey, painter and artist Truc-Anh, and filmmaker Bao Nguyen.

The show was directed by Viet Tu, with Ha Do serving as its creative director. The team behind the exhibition included production director Duong Tran Bao, storyteller Quynh Huong and media coordinator Tung Leo.

Curated by Arlettle Quynh-Anh Tran, Cuc Im Lang was the result of dialogues surrounding themes, approaches and practices contained in Tri’s creations. Taken out of the conventional context of runways, white-walled galleries or theaters and re-situated under different lights, the exhibition invited viewers to encounter fashion items and contemporary artworks on the fringe of their self-referential disciplinary discourses. On these margins, one discovered delightful encounters and ideas conveyed through a plethora of different mediums.

Natural Intimacies

Cong Tri has the profound ability to imitate a texture, object or plant using fabric through precision and attention to every minute detail. In No.3 collection Cam (Sense), for example, Tri evokes Vietnam's rural life and countryside scenery: thatched-roofs made of cogon grasses, straws, and crop residue are recreated in an outfit using chiffon. Áo tơi, a coat often made from thatched palm leaves worn by farmers to shelter them from the sun and rain, is also remade in this way in another outfit in the collection.

In another look, Tri imitates the cúc vạn thọ (Mexican marigolds) bushes he’s seen in the countryside using thousands of small pieces of fabric stitched together. The appearance of ecological worlds in Tri’s design is refreshing considering how the industrial ethos of production tends to separate manmade goods from nature, as if fabrics and materials aren’t extracted from plants, trees and the soil of any particular place.

The paradox and pitfalls of a human-versus-nature division, characterized by man's desire to tame and overcome nature without questioning their position as part of it, unified Tri and VUUV’s work, which served as the room where the No.3 collection was showcased.

VUUV's room.

For the involved artists, goods, clothes and architectural forms presented different stages of transformation of worlds and ecologies, rather than human dominion over nature. VUUV’s space situated the outfits within three different layers made entirely of bamboo. The outermost layer reminded one of the familiar bamboo mats that lulled many generations to sleep before modern mattress beds entered Vietnam. The second layer consisted of bamboo strips woven into triangle wattles, with a high tower made of fishing baskets comprising the third.

Tri’s re-creation of materials is seen again in No.4 collection Tieng Vong (Echo), which uses taffeta fabric extensively to imitate the metallic sheen of machines. No.6 Collection Nam (Mushroom) employs some of the techniques seen in Tri’s third collection — meticulous crafts and embellishments call to mind the appearance of a fungus. Em Hoa, Tri's tenth collection, also celebrates flowers recreated with fabrics.

No.4 Tieng Vong (Echo).

Layers of careful craftsmanship rest at the heart of Tri’s artistic practice, and thus in the very first exhibition room that held Tri’s first collection, de-layering one’s self and craft serves as the central theme. No.1 Trang (White Impress), and the room that held it, uses white as a unifying color and metaphor for a blank canvas; a mute color that can serve both as an ending and a beginning.

For the first room, visual artist Ngo Dinh Bao Chau’s work Layered Ego 1 engages directly with layering and de-layering as the main artistic technique. Doubling as a passageway into the room, the work consists of two black panels on which white illustrations of organisms were created using trucchigraphy, a paper art technique that uses water pressure to remove different layers of paper in order to create different shades and textures. Different types of materials are employed, including corn silks, water lettuce and bamboo.

The result is a microscopic view of the biological makeup of life — the trúc chỉ technique creates a visual effect that replicates elements of the White Impress outfits, in which chiffon and taffeta fabrics are woven into the dress to imitates paper folds.

Chau’s second artwork installs different types of chairs painted white around the mannequins to create a close circle, as if there were invisible spectators looking at the outfits. The chairs can also read as the artist’s internal multiplicities and thus how looking into oneself from different perspectives can serve as part of one's own self-searching journey.

On the gate leading to the second room was Chau’s third artwork, which consists of a metallic, foil-like curtain on which indecipherable sentences are printed in a way that resembles paper that has gone through a shredder machine. While the first two works push forward the idea of exposing and dissecting oneself, the curtain holds back on this exposure and clarity; only opening a window into ones’ memories. The only things viewers can gather from the work are fragmented images: young grasses, dew drops, long nails, dirt, lipstick stains, red nails.

Traditions on Trial

Another recurring theme that Tri deals with is the artist’s relationship with traditions. Áo dài appears twice in the exhibition. The first appearance is in Tri’s second collection, Cai Lai (Contestation), which, in Tri’s own words, takes inspiration from “a girl with tattoos, the flap of her áo dài bundled up and tied around her waist, riding a fast motorcycle from school to a bar.”

Áo dài as a cultural object stands at the intersection of both lived and imagined traditions: it is lived as different forms of áo dài were worn by Vietnamese of past generations and it is imagined in the sense that it can serve as a national symbol exclusive to feminine subjects, especially when it comes to the modern áo dài. From an outsider's perspective, áo dài can also be exotic, orientalist or a strange flavor to be commodified and exhibited.

Similar to dealing with other traditional texts and objects, the desire to engage or neglect the territory of tradition, presents a source of struggle for the artist, as Tri likens it to the relationship we have with elderly parents.

“Should a designer borrow tradition to 'beseech affinity,' or should he struggle to break out of it? I think of tradition as a warehouse open to all of us to comb through […] From this ‘warehouse’ of memory, I collect naive clumsiness, sometimes even a frailty of the mind,” noted the exhibition's text.

No.2, áo dài contains objects that are also subjected to modification, transgression and usage that may or may not resist already-attached meanings and symbols society has placed upon the dress. “Áo dài bundled up and tied around her waist” is in fact how many school girls wear their áo dài behind the back of teachers and outside the eyes of school authorities, when they feel like wearing a sacred symbol is too much of a burden for a student to handle.

Tattoos, embedded into the sleeves of Tri’s outfits, open the possibility of transforming something sacred, totalizing and fixed into personal expressions. However, in the second work, the indecision between breaking out and conforming looms large. Ngo Thanh Phuong captures this contention perfectly in her multi-channel performance video.

The dancers wearing the modified áo dài are sometimes alone and sometimes interacting with another dancer, moving in a way that is comforting at times and disturbing at others. In one moment a dancer feels compliant and comfortable in their own skin, in another they’re fighting themselves out of the clothes. The urge to resist or to embrace, and to cater to an audience or not, simultaneously exist in the same way modification and transgression can exist alongside the condition of being subjected to tradition’s very existence.

Phuong’s performance video converses with our own cultural and social baggage concerning the so-called national costume, and hints at the notion of national identity at large — isn’t identity directly linked to how we move our tongues, our bodies, our selves?

Áo dài appears again in No.7 Cam On Sai Gon (Thank You Sai Gon), which was placed in a room created by French artist and photographer Hua Nhu Xuan. In the fashion collection, Tri resists the modern áo dài’s common association with symbols and sacredness by placing pixelated photos of street signs, food, street DIY advertisements and daily newspapers on the dress using heat transfer printing.

The vernacular images and camp sensibilities in Cam On Sai Gon make the dress more playful and less serious, which is how Tri frames his memory of Saigon. Xuan shares Tri’s affinity for nostalgia and continues this dialogue from her diasporic perspective. Resituating the áo dài in the domains of monuments, Xuan places golden fortune trees under Tri’s áo dài that hang from running ceiling fans.

Truc-Anh, a French Vietnamese painter, takes the flirtation with sacredness to a different level. Presenting his artworks alongside Cong Tri’s ninth collection Lua (Rice) — which showcases fine silks from Lanh My A, a famous silk village in the Tan Chau silk region in An Giang Province in the Mekong Delta — Truc-Anh nested a world inside the exhibition space. Like the way Cong Tri weaves the entire landscape of the Mekong Delta into his work, Truc-Anh's design is epitomized by rice, Vietnamese most famous crop.

“Velvet and Lanh My A Silk are plaited into ripe rice, [mắc nưa] fruit and silk threads plaited into layers along the seams, motif of rice leaves pleating and sophisticated embellishment. Each detail receives thorough and sophisticated care, amounting to thousands of handicraft hours by artisans,” reads the exhibition brochure.

Meshing the sacred and the everyday, Truc-Anh references the space goddesses, serpents, rice, rivers and moons to create an impressive spectacle that straddles the line between reality and fiction in an unapologetic ode to the Mekong Delta’s landscape and spirits.

The Body

Throughout the dialogues in Cuc Im Lang, ruminations on the human body and its place in the world emerge. The topic of dissecting the body was manifested in the fourth room, which held a video by Lu Yang and Cong Tri’s No.4 collection Cat Lop (Dissection).

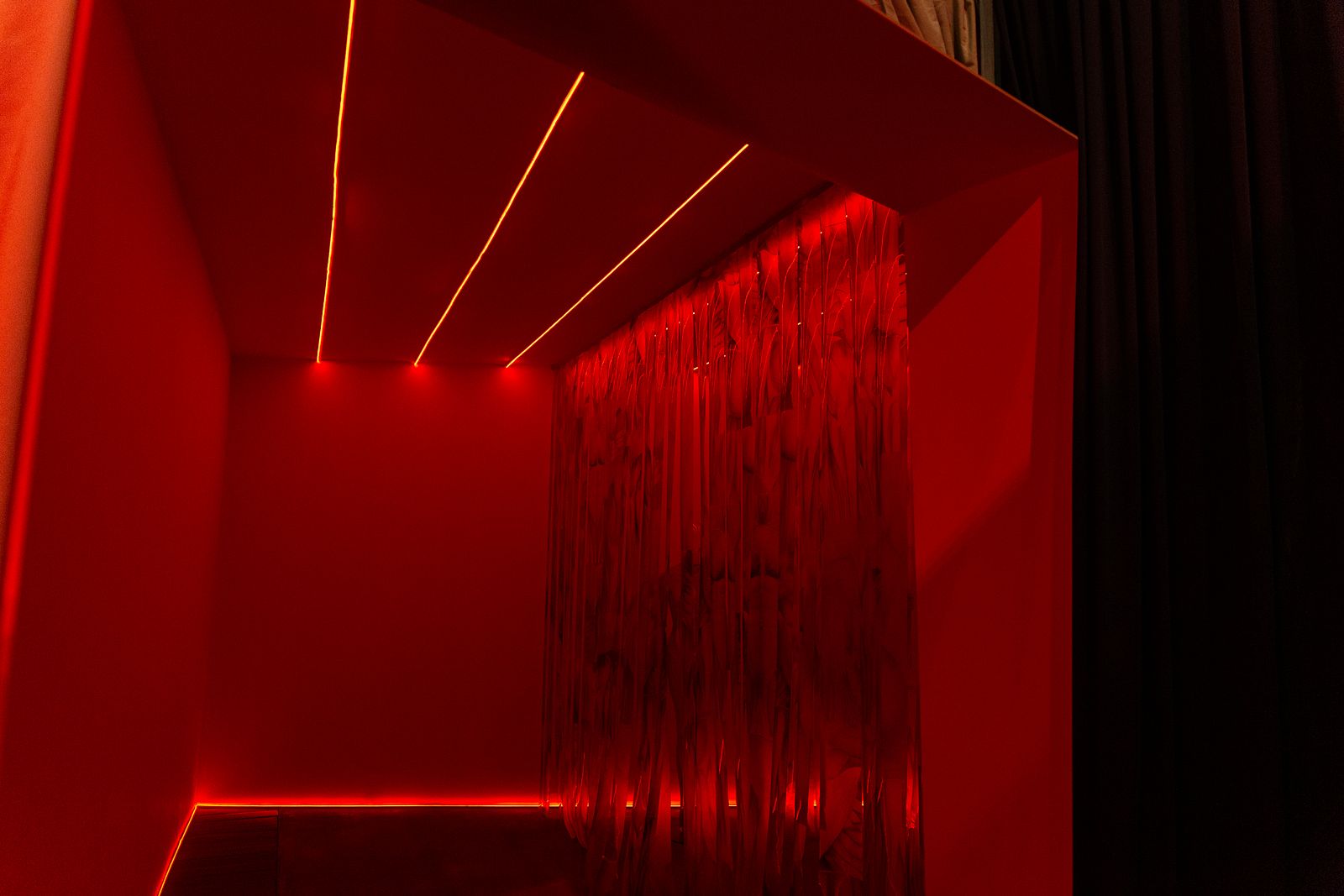

Red fluorescent lights penetrated the room’s entrance, reminding viewers of ambulance beacons, infrared lamps used for muscle treatments, digital clocks, night clubs, LED lightboxes and the glow emanating from ancestral altars. The atmosphere reflected the exhibition's shift to medical and techno-scientific language in both the fashion designs and the artworks. Viewers instantly felt exposed as if being put under the scrutiny of a medical facility since red lights also make one’s veins darker and more visible.

Indeed, the meticulous eyes Cong Tri once laid on plants, straws and husks have shifted to his own body in the fourth collection, which arose after Tri examined his own body's CT scan. Cat Lop takes each element inside a human body: blood, veins, muscles and hair as the main concept for each outfit. Again, Tri’s attention to detail manages to recreate floating blood, long and thick hair locks and muscles using fabric and heat press printing.

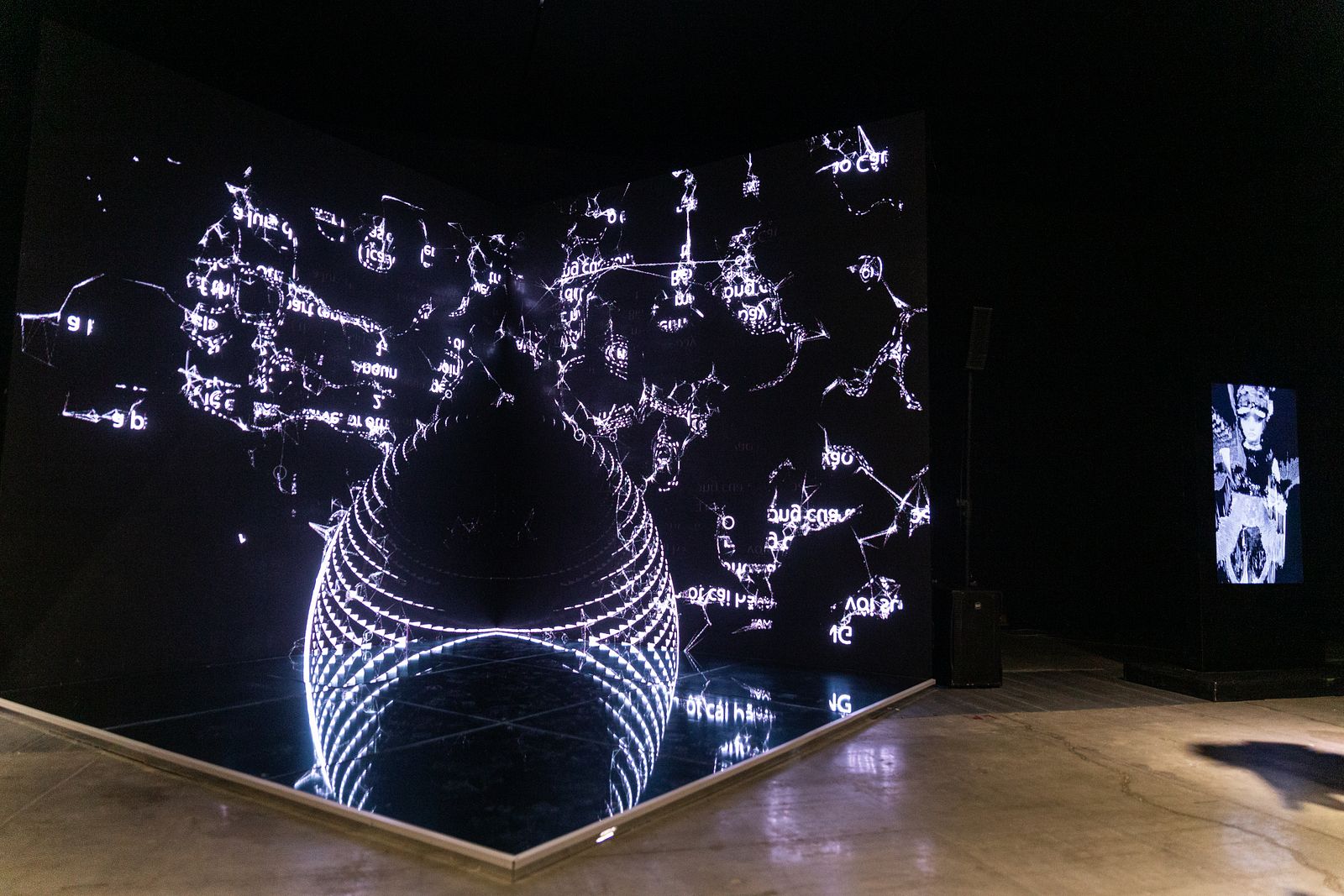

Lu Yang, also looking into her own body as the primary source of inspiration, scanned herself through a 3D modeling program to create a nonsexual, non-gendered digital self. Yang placed this digital person through different stages of body modification and manipulated her digital self with neuro-scientific technology. Titled Delusional Mandala, the video captures this process from the moment Yang’s digital self was born until its presumed death.

Yang performed computer-mediated stereotactic surgery, a form of surgical intervention that uses a 3D coordinate system along with deep brain stimulation and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on herself to inject it with religious and medicinal beliefs. Yang’s work can be seen as a subtle critique on the mechanization of the body as the delusions that her digital existence hold are rooted in the belief that the body can be fixed, rewired and reconfigured to serve certain purposes.

Both artworks then contemplate the age-old question of human ontology and consciousness and whether these concepts adhere to the physical body. While Yang marvels at the ability to manipulates her digital flesh, Tri is in awe of the flesh as it is.

“Studying the map of blood vessels, the system of muscles and the joints of bones, I realize the human body is a work of sublime beauty—a perfect design by nature itself—bursting with life and a divine-like fairytale garden,” writes Tri.

In the next room, previous hints about the pessimism towards mechanization and digitalization received further elaboration. Cong Tri’s No.5 collection Troi (Bound) deals with human dependencies on machines and technology that in turn hold humans captive to affordability and convenience.

Truong Cong Tung, in response to Tri’s design, created a beautiful ruin in which digital scraps and technoscientific logic coexist with bugs, plants and spider webs. On a wall of the passageway leading into the room is a chalk drawing of unknown mechanics, physics equations, flowers and insects. On another are three lightboxes that merge different layers of printed utterances, mechanical drawings, math formula and cosmic illustrations. Tung merges images of science and modernity’s promises of disenchantment against the backdrop of enchanting lives. Inside, mannequins wearing Tri’s outfits were situated under a gigantic structure covered by dusty old computer keyboards. For some, the keyboard even becomes their primary mode of engaging with the world.

The works critique our increasing dependency on machines and the mechanization of the body under productivism. In No.8 Tieng Voi (Echo), Tung Monkey places Cong Tri’s outfits in an atmosphere of deep computer illustrations and holograms. Cameras and machine lenses are placed on top of the mannequin’s head as a metaphor for humans becoming the machine themselves, with the body simply a device for broadcasting.

Truong Cong Tung, on the other hand, locates his vantage point from the ecological world. An embryo emerging from computer wreckage; spider webs hanging on keyboards; tree branches reaching out to the light beneath the façade of digital civilization — the world we’re living in is always morphing despite attempts to destroy and build anew. There is a strange poetic sensibility in Tung’s installation as he shows how natural elements always reemerge, like the embryo yearning for life out of digital ruins.

Tung Monkey's room.

The natural world makes another appearance in Nam (Mushroom), Tri’s sixth collection. This time, Tri turns his focus from human anatomy to that of a fungus. The artwork was accompanied by a dance performance choreographed by Alexander Tu, which uses the poem 'Mozliwosci' by Wislawa Szymboska as the narration to the dancers' movements. Titled Brave New World, the dance piece recreates the structure of a mushroom’s DNA as a manifesto for preferring the small over the grandiose.

The exhibition ended with Tri’s 2019 collection Em Hoa and an accompanying short film by Bao Nguyen. Em Hoa takes inspiration from flower street vendors with flowers on their back, which Tri considers a sight of beauty amidst the chaos of city life. The film stays true to the design's spirit, telling a story of a young flower vendor’s daughter taking her mother's job for granted before finally realizing its beauty. The film served as a heartwarming conclusion to Cuc Im Lang, a celebration of crafts, beauty and dialogues.

Nam (Mushroom).

Bao Nguyen's film In The Forest, There Is A Door.