We began our journey in front of a bank where the street Trần Nhật Duật turned into Chợ Gạo.

We started here because about 200 years ago, this area was called Hà Khẩu, or the Mouth of the River. The wide street of Trần Nhật Duật used to be the Red River, and the part turning into Chợ Gạo was where it split into Tô Lịch River. That day, Nguyễn Vũ Hải led us on a walking tour titled Dấu sông hồn phố — a journey tracing the vestige of Tô Lịch.

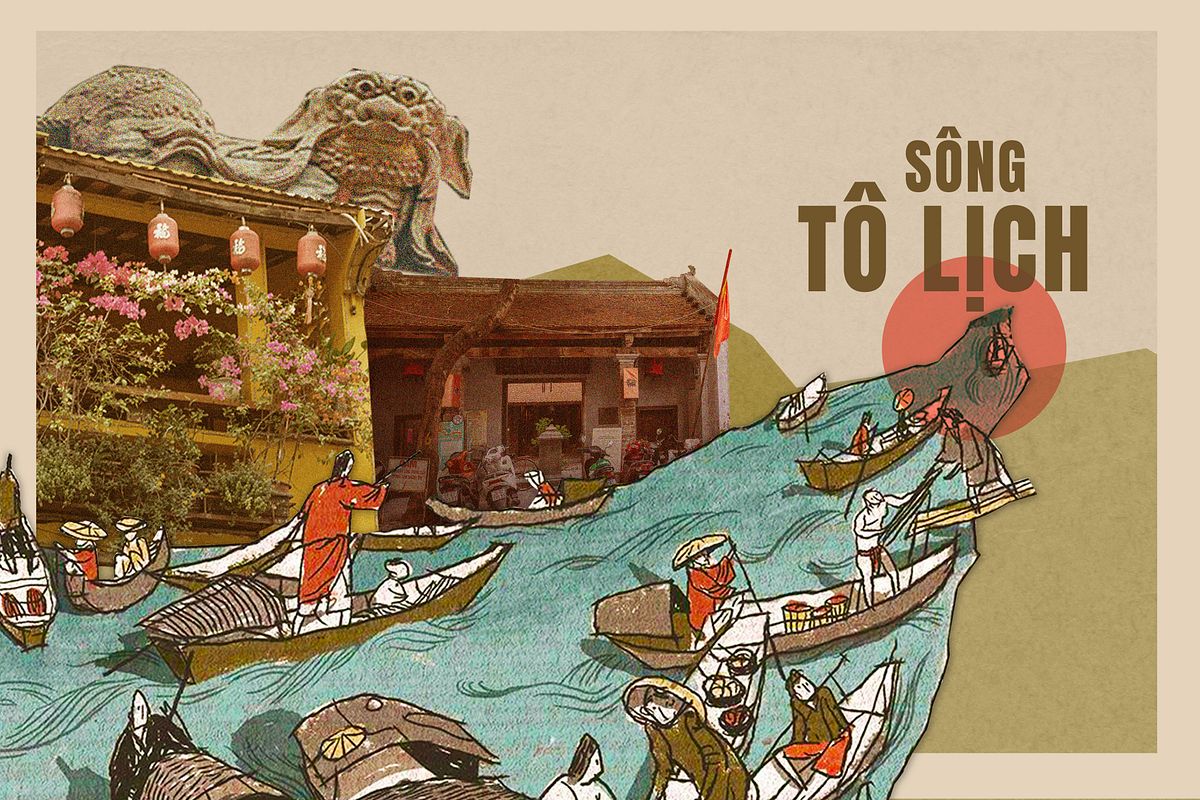

Trần Nhật Duật nowadays and the confluence of the Red River and Tô Lịch river back then, as drawn by artist Thành Phong.

When I was young, I’d often pass by the portion of the river on Thụy Khuê Street while riding my bike to school. The rancid smell from the blackened water always made me wonder: Why did people call it a river? Clearly it was a sewer. But the stories told during Hải’s tour taught me that the river’s life was a legend.

Hải said that the name Tô Lịch was mentioned in history books thousands of years ago. When Vietnam was still a part of China, Cao Biền, a famous Chinese geomancer, had a magical battle with Long Đỗ — the dragon god of Tô Lịch River. Cao Biền drove stakes into the river to subdue the god, but the stakes all shot right back up. Cao Biền realized he was outmatched, so he built a temple for the deity, and then raised Đại La citadel. Because the citadel ran along Long Đỗ’s river, it was also called Long Biên, or the Dragon Border.

The citadel following the Tô Lịch River, as seen in the Atlas of Hồng Đức (1490).

When was Long Biên raised?

Neither tall nor short.

Beautiful on the outskirts.

Strong water flows below.

I read that poem a while ago. Only now did I understand the mighty flow was Tô Lịch River, though that section was filled in a long time ago. But people can still feel the “neither short nor tall” height these days. Using a couple of old maps, Hải showed us how to re-trace the ancient citadel walls. I was surprised to see how big it must have been when drawing lines across Yên Phụ, Hoàng Hoa Thám, Bưởi, Đê La Thành — all the streets that you must go uphill to reach.

Tracing with citadel wall and the past river flow based on an old map.

The river’s legend continued once Vietnam escaped northern domination. In 1010, King Lý Thái Tổ moved the court to Thăng Long. The king wanted to fortify the citadel, but the walls kept collapsing. The king ordered people to pray to Long Đỗ, upon which they witnessed a white horse walking out from the temple. The king followed the horse’s footsteps to build the wall, and it became sturdy. And thus the king renamed the temple Bạch Mã, or White Horse Temple, the Eastern Sentry of Hanoi. He also declared Long Đỗ to be Thành Hoàng of Thăng Long — the tutelary deity of this land.

A map of Hanoi in 1873.

With the blessing of Long Đỗ, Thăng Long flourished. Goods and merchandise from the north flowed down the Red River, and Tô Lịch River became an important urban trading route. Hải said that there were many markets along the river. “At the confluence, there was chợ Gạo, then chợ Bạch Mã, chợ Cầu Đông, chợ Bưởi, chợ Cầu Giấy, chợ Ngọc Hà, chợ Dừa…” The Old Quarter back then was called Kẻ Chợ, or the Market People. And it was so prosperous that there was a saying: “Giàu thú quê không bằng ngồi lê Kẻ Chợ,” or “being rich in the countryside is no match for being a beggar in Kẻ Chợ.”

Chợ Cầu Đông Street, named after a bridge market lying across the river on the eastern side of the citadel.

But then a day came when human weapons eclipsed even the gods. In 1882, the French fully colonized Vietnam and turned Hanoi into the capital of Indochina. During their rule, the French dismantled the Thăng Long Citadel to build bridges, roads, and an underground sewage system.

Hải said: “Tô Lịch river was once an important trade route, a physical representation of the god. But now, after the French came and applied their urban planning, the river became a culvert.”

Hàng Đậu Water Tower, the harbinger of the era when Tô Lịch becomes a sewer instead of a major waterway.

And once the underground sewer opened, a particular species flourished: the rat. They spread the Black Plague all over the city, forcing the French to try to kill them. They hired Vietnamese to kill the rats, requesting catchers to turn in rat tails as proof. Each tail was worth four Indochinese piastres.

“With such a good price,” Hải continued, “locals began to catch rats, cut the tails off, then release them so they can keep breeding. Then rat farms emerged around the city, as well as a network to deliver rats here from the countryside.”

One day, a French official saw a tail-less rat running on the street. From then on, rat hunters had to turn in a whole rat. But business continued to boom until the price was cut so low — from four piastres for one rat to one piastre for five rats — that nobody bothered killing rats anymore. The French also shifted their plague-controlling efforts to medical measures rather than eliminating the species.

Thăng Long's Northern Gate on Phan Đình Phùng Street.

Hải said the rat story was just one example of how people live with the world around them. From a life in harmony with nature to one of management, exploitation, and discard. Tô Lịch has remained a sewage channel to this day.

We ended our tour at the Northern Gate, the last remnant of the old citadel. When they ordered its demolition, the French kept the gate because it contained the imprinted cannonball holes making the day the citadel fell. As I stood there, looking at the heavy traffic on Phan Đình Phùng, it was hard to imagine that Tô Lịch river used to run through here. Suddenly I felt incredibly sad, as if the city had lost its roots.

Phan Đình Phùng Street today.

One morning after the trip with Hải, as I was lighting an incense stick on the altar, I thought of the god Long Đỗ. Instead of praying to my ancestor as usual, I said gratitude to the god for protecting this city, and asked that he keep looking out for my family, my friends, and all the souls who lived here. The name Tô Lịch for me had transformed from something filthy to something sacred. I heard there had been talks recently about restoring the river to its past glory. Hopefully, one day it will regain its place as the life force of Hanoi.

This article was originally published in 2023.