While Saigoneer’s previous installment in our Food History series touched on the evolution of bánh xèo, a light, airy crepe that screams summer with every bite, this week’s dish belongs to the other end of the spectrum: bánh Trung Thu, or mooncake, whose rich, savory taste perfectly encapsulates the essence of autumn.

The most significant clue of the origin of this ubiquitous baked pastry is included in its name. “Trung Thu” means mid-autumn, a special occasion in countries that still utilize the lunar calendar, like Vietnam and China. Every lunar year, the 15th day of the eighth month is reserved for moon-themed celebrations and family reunions. In a way, it’s like September’s version of Tet. This timing can be attributed to the ancient Chinese agricultural timeline, as farmers of old usually finished their harvests by mid-autumn, which marks the end of the harvest season and the best time for some much-deserved baking and boozing.

Ancient Chinese farming communities had already been celebrating mid-autumn as a harvest festival for years before the Song dynasty (960 – 1279) officially earmarked this day as the “mid-autumn festival”. It’s safe to assume that this tradition made its way to Vietnam during the country’s period as a Chinese colony, along with many other cultural traits and celebrations, such as Tet. However, the festive occasion has been largely contextualized since then to fit in with local customs.

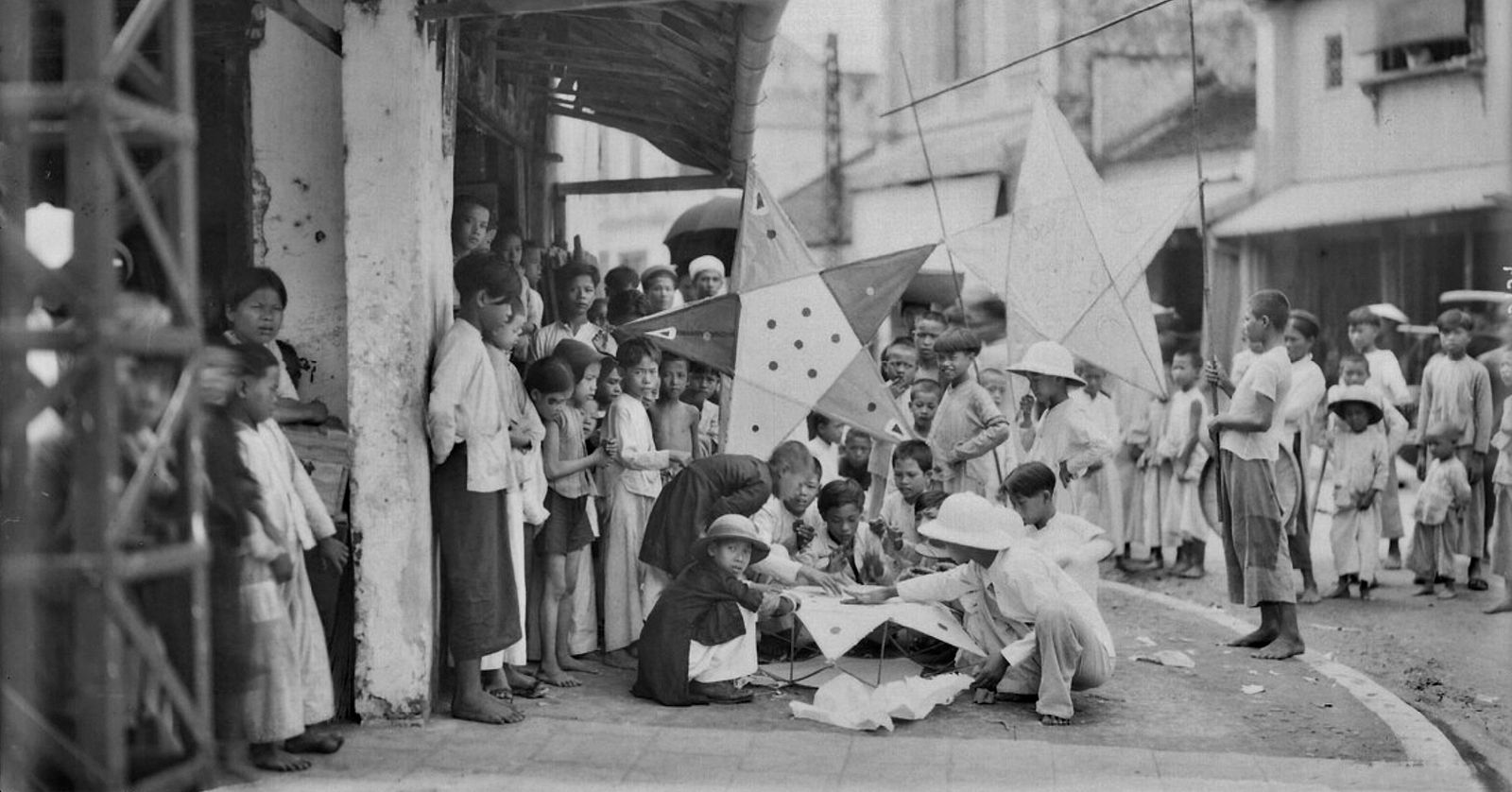

While China, Malaysia and Singapore's mid-autumn festivals, and even South Korea’s Chuseok festival, place more emphasis on familial celebrations and giving thanks for a bountiful harvest, in Vietnam, Trung Thu has taken on a different meaning as a children’s festival. This unique focus is reflected in the way Vietnamese bake mooncakes: the pastries are sometimes made from molds shaped like animals. These can take the form of creatures from the Chinese zodiac, or characters from Vietnamese mid-autumn folklore such as rabbits and golden carps.

Mid-autumn is mainly a children's festival in Vietnam. Photo via VnPhoto.

Determining the exact year when ancient Vietnamese started celebrating Trung Thu with mooncakes is not an easy feat, as the cultural festival is barely mentioned in historical literature. However, the existence of bánh Trung Thu is undoubtedly rooted in a long-enduring Asian tradition of moon worship. Mooncakes are almost always round, symbolizing the moon. They are baked mainly as a shared dish to be relished as a family on the day of Trung Thu; and secondly, as aesthetically pleasing creations to be gifted to friends and family.

Mooncake bakeries may want you to believe that there are thousands of different forms of mooncakes, but in reality, in Vietnam, they boil down to two main types: baked mooncakes (bánh thập cẩm) and sticky-rice mooncakes (bánh dẻo). The former is pretty self-explanatory, as one only needs to take a stroll down Nguyen Tri Phuong or Hoang Van Thu to see them in the wild, at a dime a dozen. The latter, despite being made from the same base as Japanese mochi, tends to be harder and doesn’t share the same tantalizingly viscous quality of the Japanese dessert. Well, at least the mass-produced ones don’t, anyway.

Most of Vietnam’s baked mooncakes are descendants of Cantonese-style mooncakes, which originated in China’s Guangdong Province. This is evidenced in the savory filling one almost always comes across in baked mooncakes: a form of roast protein, typically chicken or pork; melon or lotus seeds; and various forms of nuts and dried candied fruits. Vietnamese bakers usually add salted egg yolks to balance out the sweetness of the other ingredients. The number of yolks ranges from one to four, depending on the price of the cake, but the number four is ideal, as it represents the four phases of the moon. The addition of egg yolks also ties in to the festival’s overarching theme of moon worship, as the yolks resemble the moon.

Baked mooncakes are usually enjoyed with hot green tea to balance out their sweet taste. Photo via Maxxelli-Blog.

Sticky-rice mooncakes are decidedly simpler than their baked counterparts, usually featuring only one or two fillings, typically classic Vietnamese flavors such as pandan, taro, coconut or mashed mung beans. In recent years, young chefs from contemporary bakeries have added a modern twist to the old mid-autumn fare, experimenting with new filling flavors such as tiramisu, matcha or even ice cream, with various degrees of success.

Through centuries of tradition, these pastries have become an indispensable part of mid-autumn festivities, although it’s a huge letdown that they have also come to symbolize an ugly aspect of local gift-giving obligations. The reality is that for years now, the local market has been inundated by mass-produced cakes that have, quite frankly, made a mockery out of proper mooncakes. These haphazardly rendered pastries are impossibly dense, cloyingly sweet and pack as much as 1,000 calories per cake. Recently, the Hong Kong government even issued a PSA to its citizens cautioning them against consuming too much of the festive treats and advising them to "maintain a balanced diet and avoid excessive eating of mooncakes".

Premium mid-autumn gift sets on offer. Photo via Bao Moi.

The reason why these store-bought cakes are so bad ties in with the aforementioned gift-giving culture, in which buyers don’t care about the taste of the cakes, while those who do don’t buy them. Trung Thu has taken on a different significance, more than just a mere occasion for kids to have fun: it’s now also a time to shower one’s professional network with gifts, and the innocent mooncake has become the inadvertent centerpiece of this complicated social contract. Nowadays, a lavish mid-autumn gift set ranges in price from VND2 million to VND14 million, while the gift boxes also boast choice liquors and even gold-plated cutlery.

However, some Vietnamese bakeries are also steering their cake-making traditions in a more positive direction, where younger indie bakers churn out homemade, healthier renditions of the traditional mooncakes. With a simple search of local social media, one can find a plethora of small bakeries offering small batches of mooncakes, partially capitalizing on recent public concerns over mass-produced products with questionable ingredients. These new pastry chefs are also infusing their creations with new touches from Western cuisine, such as making use of cream cheese or fresh fruit to improve the flavor profile of their cakes, giving the pastries a fresher edge.

At the end of the day, despite their overly sweet nature and recent bad rap, mooncakes are without doubt an important holiday feature, without which the mid-autumn celebration in Vietnam would be incomplete. So the next time someone offers you a piece of mooncake during a visit home, grin and bear it, because that’s what the cake was originally meant to be: a decadent treat to be shared between friends and family.