How would you tell the story of your birth soil?

If asked to recount the history of your hometown, you might share an elliptical assemblage of anecdotes, memories, myths, quotes and half-remembered truths. In your attempts to provide a full description, you’d likely leap back and forth in time, tether together the personal and the political to construct meaning, and finally offer up a handful of fragments that you hope constitute a coherent whole while openly questioning if such a thing were even possible.

A montage of rural Vietnam

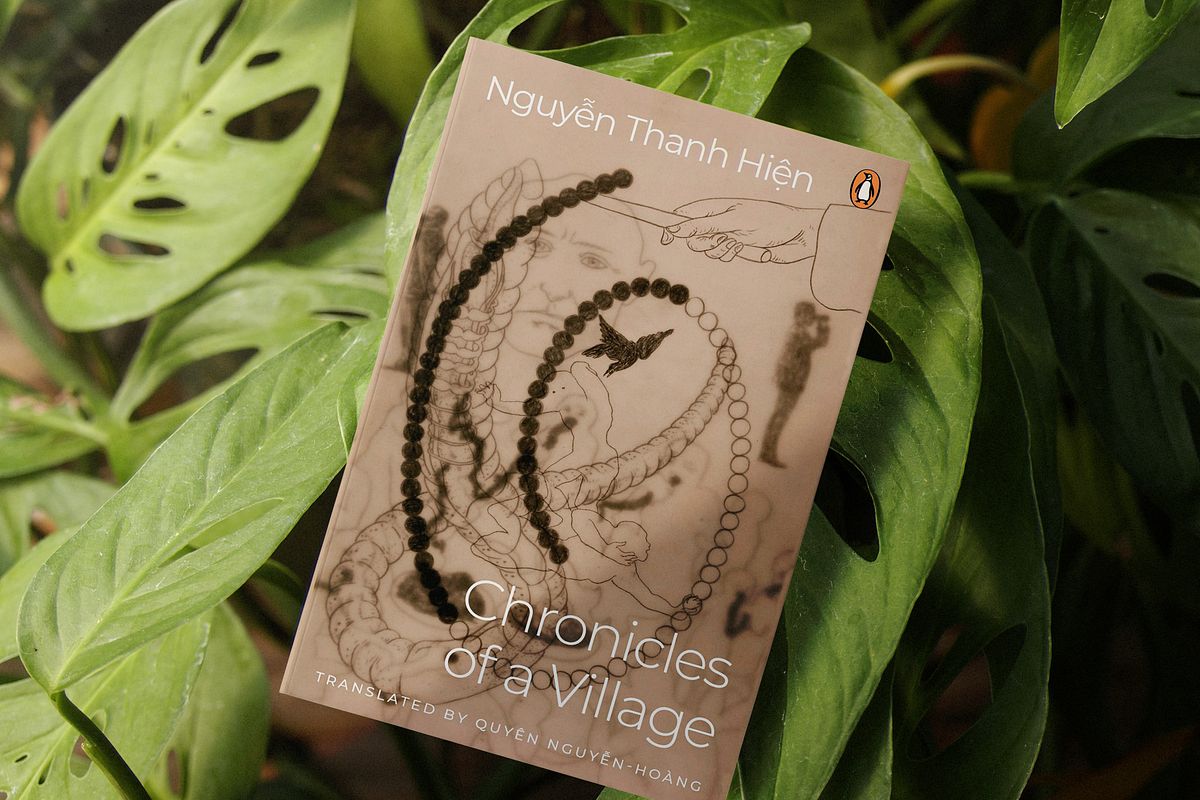

“It is true that the village where I was born remains an ever thick and impenetrable land inside my heart,” writes the unnamed narrator in Chronicles of a Village as he trudges along with his efforts to record the history of his anonymous village. The recently translated work of fiction by writer Nguyễn Thanh Hiện is a collection of brief scenes, descriptions, conversations and stories focused on the people and environment of a rural Vietnamese village during the 20th century. By the end of the book, the village may remain unpenetrated, but readers will understand why it has lodged itself so deeply in the narrator’s chest.

To explore his life in the village, the narrator offers snapshot experiences from his childhood. He gathers mountain fronds to weave raincoats, listens to tokay geckos at night, watches a neighbor construct a traditional rice-mortar binder, learns how to plow the fields and recounts the season when his father tried to replace him as guardian of the crops with a statue made of sticks. Juxtaposed with cataclysmic violence and struggles during the same time period, the selection of anecdotes does justice to the baffling ability of the human brain to store momentous or traumatic events alongside mundane, potentially meaningless ones. In vivid prose, the narrator thus depicts a humble life reliant on and in close commune with the natural world that would be typical of many people of his age without the assumption that anything holds specific significance that can be articulated.

"In my village, sorrows are like the late afternoon winds, rain or shine, they are always blowing…I have lived alone with the sorrows that haunt the land of ancestral worry."

The book is not a loving homage to a simple, bucolic lifestyle, however. “In my village, sorrows are like the late afternoon winds, rain or shine, they are always blowing…I have lived alone with the sorrows that haunt the land of ancestral worry,” the narrator admits. Indeed, the world’s cruel caprices arrive frequently. The narrator’s mother is killed in a bombing raid, villagers are murdered during frequent purges, and an 18th-century scholar arrives in a dream to tell an occasion of a senseless and seemingly random murder for which the perpetrator receives no punishment. Buttressing the simple daily life of the narrator and his family, these frequent miseries and their matter-of-fact framing cast a depressing tone across the book underscoring the futility of the human condition.

While the work mostly focuses on the narrator’s experiences, other characters arrive to share slivers of their larger experiences via real or imagined conversations as well as quoted texts and notes. For example, Mr. Quì, the village headman, loses his position when the dynasty he served is dethroned. He doesn’t rage or hold grudges but rather “collapsed in peace,” ignoring inquires from humans and bulbuls alike. Elsewhere, a man named Mr. Hoành, an accomplished scholar, retreats from the world and develops a way of life dedicated to wine as celebrated with a great festival once a year. But Mr. Hoàn disappears, like all the secondary characters, before explaining or expanding upon the significance of their tales. “I wouldn’t know the answer,” the narrator laments regarding what impact any of their efforts in the world had.

Blending the real and the ethereal

A murky layer of partial truth separates history from legend that Nguyễn Thanh Hiện dives into headfirst. Women turned to stone; tigers, elephants and bears consciously offer land for human development; and ancestors who were once able to capture ghosts are acknowledged beside French colonialists, automobiles and lucid memories of children gathering to weave bolts of fabric in flickering lamplight. The author seems to argue that it isn’t a matter of whether a dream-vision, historical text, or a first-hand memory is the most trustworthy source, but rather what does it matter? In other words, when the narrator finally learns that the lullaby “look up at the Chóp Vung Mountain, watch how the cats lie round the two lone hares” refers to clouds and not literal animals, has he really learned anything of value about the world? And what happens once he realizes that on cloudless days he can just as easily make the cats and rabbits appear in his imagination?

The author seems to argue that it isn’t a matter of whether a dream-vision, historical text, or a first-hand memory is the most trustworthy source, but rather what does it matter?

Chronicles explores the sometimes contradictory effects of the intersections of tradition and modernity, progress and commodification. For example, the village’s first transistor radio arrives and the enchanting “speaking device” causes mayhem when the locals mishear a report and brace for an invasion that was occurring elsewhere. Meanwhile, mechanical plows usher in “a vision of democracy where the cows and the humans were friends in their daily struggles,” and pull unwitting villagers into the unavoidable world of “petty and miserable politics.” The negative effects of modernization on individuals, such as when the narrator wonders how his family will make ends meet when rubber raincoats replace the woven-reed versions they create, however, simply replace other hardships: “quiet worries about rice, clothes and the weather’s disastrous fickleness.”

In addition to its fragmented, non-linear narrative, Chronicles resembles oral storytelling in its punctuation. Absent periods, the comma-laden lines race ahead like a one-way conversation. Pauses that would invite audience feedback in another context return to the subject at hand. And like an impromptu recitation, the narrator occasionally corrects or modifies previous statements, ends anecdotes abruptly and questions the point he was even trying to make.

Deconstructing the conventional novel

In addition to the somewhat challenging style, the work does not meet any conventional expectations for what constitutes a novel regarding plot, conflict, or resolution. While the chapters layer atop one another to create textured impressions greater than their elements, most of them could be enjoyed independently as prose poems and indeed, several of the contained chapters have been published as short pieces of fiction. One should expect to find a conclusion to the book the way one expects a conclusion to a music album; there is no story arc to complete but it ends on the right note. In this case, it is the surreal return of his father who says “history is only a draft copy, son, nothing is certain, nothing is true.”

Ultimately Chronicles of a Village is a strange, difficult book that is unique amongst much of the Vietnamese literature translated into English. Reading it requires a certain faith in the text and the author’s ability to offer a satisfying experience that gathers around one like clouds snagged on a mountain peak. At one point the narrator remarks. “There is a profound philosophy of existence concealed within the deepest sentiments of human beings, something even now I haven’t fully understood.” If you agree with such a sentiment, this book demands your reading.