Don’t you find it bewildering when you have existed for centuries, and are suddenly thrust into stardom due to a small cameo in a nationalist saga?

One year in primary school, I was chosen to be part of a small team representing my school in a district-level trivia competition. The tournament pitted teams from different schools against one another in rounds of general knowledge based on the public curriculum. To prepare for the quiz, the teacher-in-charge made stacks of study notes and divided them among the five of us, so we could attempt to jam our baby brains with random factoids like what phloem and xylem are, who won the first SEA Games gold medal for Vietnam, and how many planets there were in the solar system — ah, the good ol’ days before Pluto was scathingly ostracized by mean astrophysicists.

The flower worthy of a heroine

It was through this hodgepodge of trivia that I encountered lêkima for the first time, as an aesthetic embellishment in the story of Võ Thị Sáu, a nationally revered historical figure and iconic teen guerilla fighter. As the narrative goes, Sáu joined the revolution against French colonists when she was just 14, specializing in projectiles. During an ambush, her grenade failed to explode, and she was captured. After Sáu turned 18, the French shipped her to Côn Đảo to be executed by firing squad. Following her killing, the young Bà Rịa-Vũng Tàu native became a symbol of selfless resistance, of youthful dedication, and of femininity in the face of ferocity.

While her life was short, her legacy has endured in literary works even today, as writers, auteurs and musicians pay homage to Sáu in a variety of films, songs and poems, some of which blur the line between reality and imagination. All in all, they have blended together to elevate Võ Thị Sáu from a teenage fighter into a divine entity, if the Côn Đảo shrine dedicated to her, which pilgrims frequently visit to ask for marital success, is any indication. We are not here today, however, to dissect the veracity of Sáu’s life story — and I won’t even touch that with a ten-kilometer pole — instead, let’s discuss the inseparable association between her and lêkima.

As she was being escorted from her holding cell to the firing range, she stopped at a blossoming lêkima tree, plucked some fresh flowers, and slipped them into her hair.

It’s widely believed that, during Võ Thị Sáu’s final moments, as she was being escorted from her holding cell to the firing range, she stopped at a blossoming lêkima tree, plucked some fresh flowers, and slipped them into her hair. I have long thought that the little detail symbolizes a tender facet of the human condition. It shows that, even after the months and years toiling away in captivity, Sáu’s humanity remained intact, for the ability to relish beauty is a privilege that draws the line between man and wild beasts. I had never seen or heard of lêkima until I was going through my competition history notes, but the elegance of the interaction made me think that it must bear exquisite flowers. After all, someone liked its flowers enough to decide to wear them in their last moments.

Did you know?

The bright color and texture of lêkima pulp come unnervingly close to those of a boiled egg yolk, if the yolk is slightly sweetened.

A strange fruit from South America

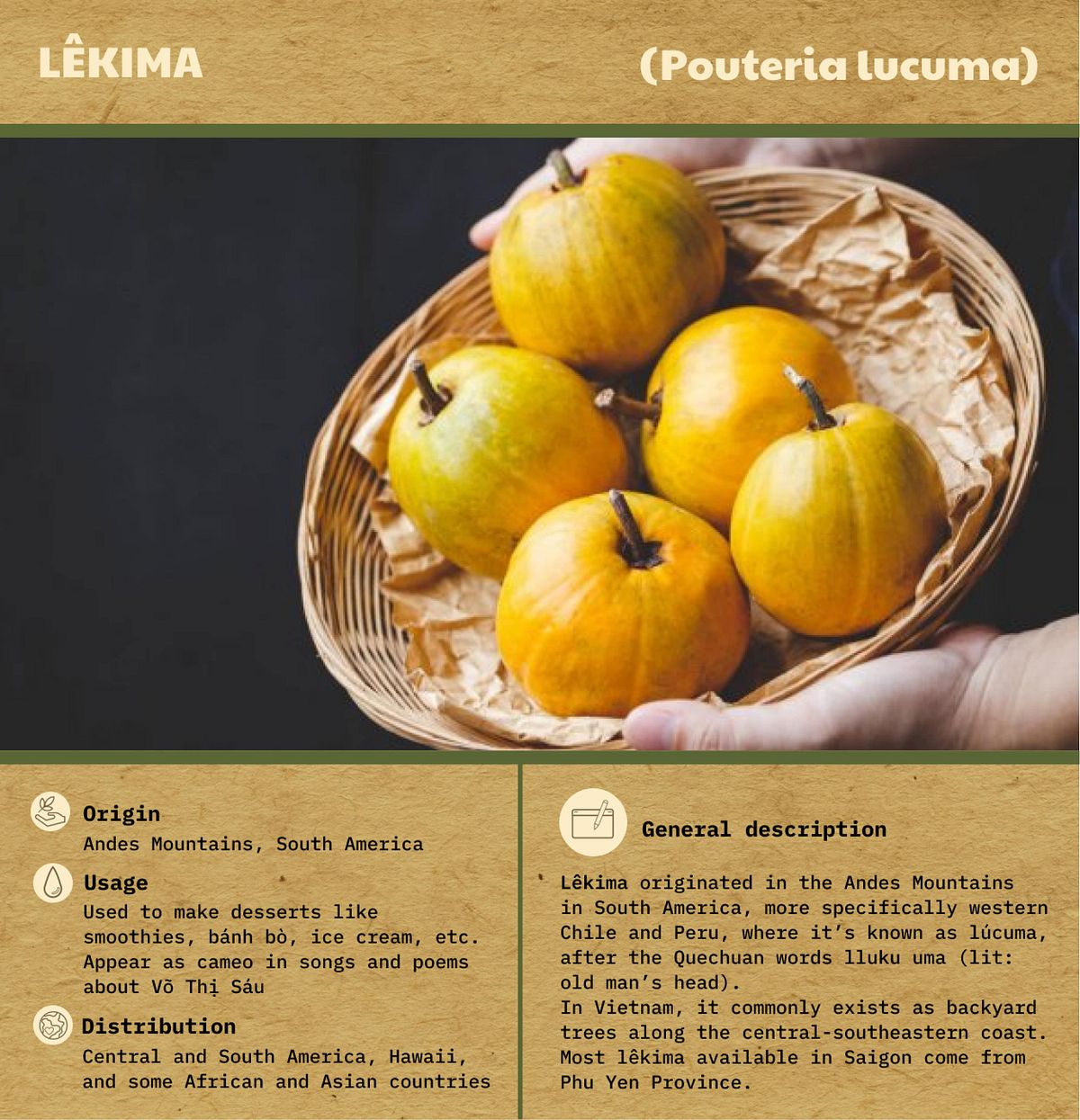

I still haven’t seen lêkima flowers in the flesh, but I have eaten its fruit: a paunchy golden handful with a slender tip like a mango. Its flavor probably gave rise to its alternative name of quả trứng gà, or eggfruit, because the inside of the fruit is fiercely yellow when ripe and doughy to taste. Both the bright color and texture come unnervingly close to those of a boiled egg yolk, if the yolk is slightly sweetened. It is delicious to consume if you know the texture beforehand and don’t take the plunge expecting tropical juiciness. Lêkima fruit doesn’t show up in markets in Vietnam as often as other cash crops like mango or rambutan, and I have a feeling that most of us don’t know what to do with it.

Lêkima doesn’t sound like a native Vietnamese word, because it’s not. And even though its role in the saga of Võ Thị Sáu has endeared lêkima to Vietnam as we come to accept it as one of our own, the fruit isn’t native to Vietnam, or even Asia. Lêkima (Pouteria lucuma) originated in the Andes Mountains in South America, more specifically western Chile and Peru, where it’s known as lúcuma, after the Quechuan words lluku uma (lit: old man’s head). It was first documented by Europeans in Ecuador in 1531, though indigenous communities have been cultivating the trees since ancient times. Archeologists have discovered its presence on ceramics at burial sites of native people in Peru.

In the following centuries, lúcuma slowly spread northwards to Central American nations like Costa Rica and Guatemala after returning exiles brought them back home. It first reached the United States in 1915, though exactly when and how it made its way to Asia remains a riddle. Prevailing theories attribute that to the boom in species transfer during the Columbian Exchange. Today, in Asia apart from Vietnam, lêkima is at least also present in Thailand, where it’s known by the name dien taw.

Lêkima, an accidental icon

Soon after her death in 1952, Võ Thị Sáu was honored by her contemporaries as a national hero, but it wasn’t until three years later that lêkima flowers started becoming intertwined in her narrative. In 1955, Phùng Quán, a soldier and later downtrodden poet, wrote the novel Vượt Côn Đảo (Escaping Côn Đảo) and the epic Tiếng Hát Trên Địa Ngục Côn Đảo (The Singing Voice on Infernal Côn Đảo).

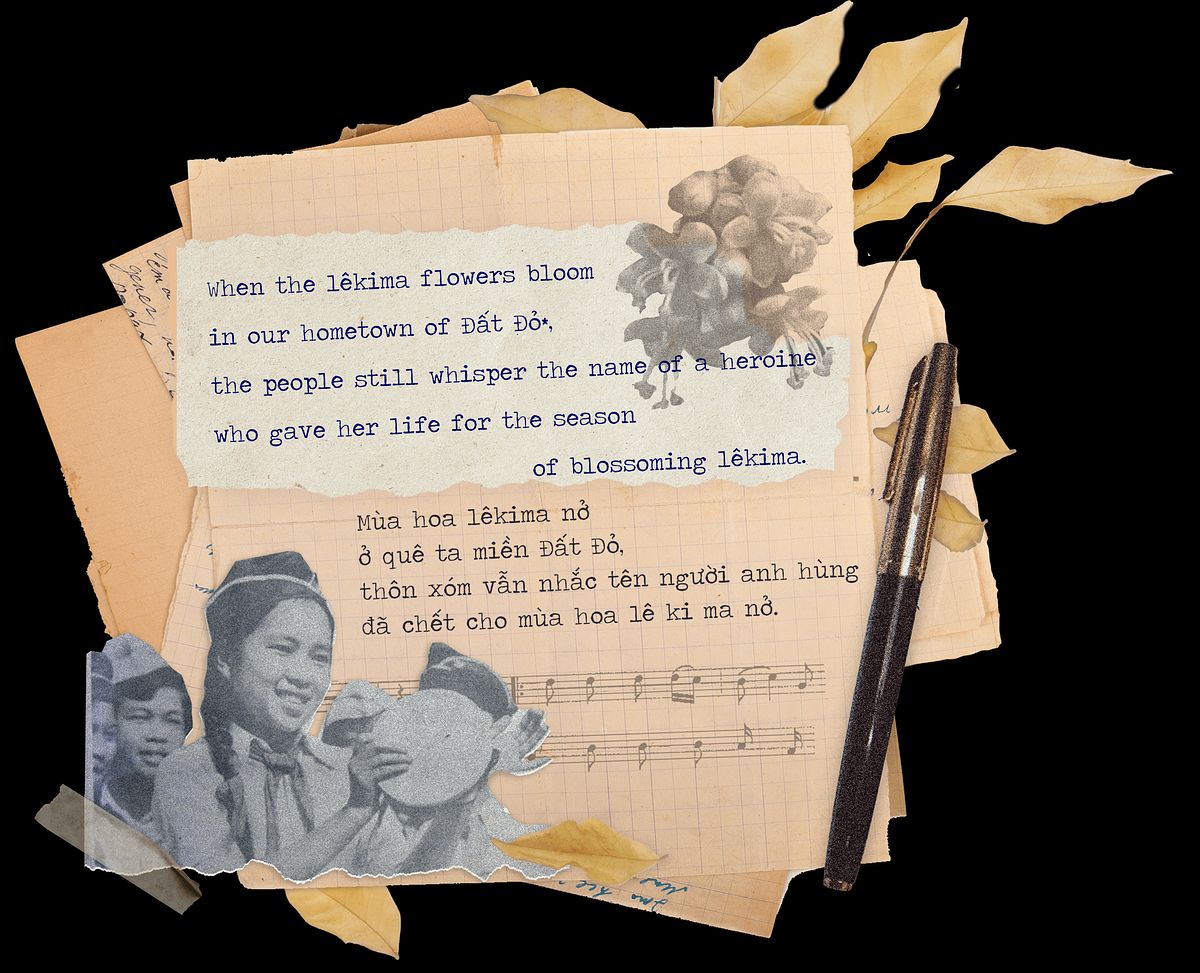

The latter tells a fictionalized, though still based on true events, account of Sáu’s last days on the prison island. In the epic, she sings revolutionary songs in her cell, she reminisces about an action-packed childhood in the resistance, and she puts flowers in her hair. The poem was instantly a hit, and even went on to win a few awards. Everybody was talking about Phùng Quán’s thunderous verses and the girl who refused to be blindfolded even for her own execution. The girl with lêkima flowers in her hair.

*Đất Đỏ District in Bà Rịa-Vũng Tàu Province is where Võ Thị Sáu was born.

‘Biết Ơn Chị Võ Thị Sáu’ is one of those vintage earworms of our generation whose words and tunes I know by heart, but could never name their title or composer. Still, the song’s simple melody and catchiness mean that it’s likely to stay in our brain until we die — and so does the season of lêkima blossoms. It’s a rather nice tune, so I don’t mind, but it felt rather bittersweet to uncover the truth of that special connection between Sáu and lêkima: It’s very likely that she never touched the flower at all, let alone slipped it in her hair, because that detail was a figment of Phùng Quán’s imagination.

‘Biết Ơn Chị Võ Thị Sáu’ is one of those vintage earworms of our generation whose words and tunes I know by heart, but could never name their title or composer.

In his essay collection Chuyện Đời Vớ Vẩn, writer Nguyễn Quang Lập recalls his visits to Hanoi when he roomed with Phùng Quán and had his ears filled with Quán’s numerous tales, including the creative process behind the Võ Thị Sáu epic.

“He [Phùng Quán] didn’t know what lêkima was. He thought ‘It has a beautiful name so the flowers must be equally pretty’,” Lập writes in Vietnamese. “Later on, he discovered that it was simply eggfruit, with its mediocre flowers and sticky sap. 'No one would ever think to put these sticky blossoms in their hair,' Quán laughed. He said that ever since, whenever one writes about Võ Thị Sáu, they will end up putting that detail in.”

By all accounts, it’s apparent that lêkima — both the flower and the fruit — lives a middling existence, if one were to judge fruits by taste and aesthetic appeal. Lêkima’s claim to fame was the result of literary improv, but does it matter? It still makes for a pleasant sinh tố, inspired the creation of a classic tune, and if one grew up with lêkima, it may serve as a fond reminder of their innocent yesteryears.