When you think of ways to combat the inevitable ravages of climate change and sea level rise, what comes to mind?

Perhaps sea walls and other man-made barriers? Solar panels? More far-fetched possibilities like floating cities, or even evacuating the planet altogether, à la Interstellar?

While all of the above have their own uses, nature has actually presented us with a phenomenal tool to protect coastal communities while also absorbing carbon dioxide: the many species of humble mangrove, or thực vật ngập mặn.

Thực vật ngập mặn first sprouted from Earth’s primordial ooze about 75 million years ago, and they are now distributed throughout the world, though almost entirely between the latitudes of 30 degrees N and 30 degrees S, with the greatest concentration within 5 degrees of the equator.

Did you know?

Thực vật ngập mặn first sprouted from Earth’s primordial ooze about 75 million years ago.

There are 110 recognized thực vật ngập mặn species, 54 of which are considered “true mangroves,” meaning they are only found in mangrove habitats. This is where naming conventions get a bit confusing: in Vietnamese, rừng ngập mặn refers to a mangrove biome, such as Cần Giờ in Saigon, which includes flora other than mangroves.

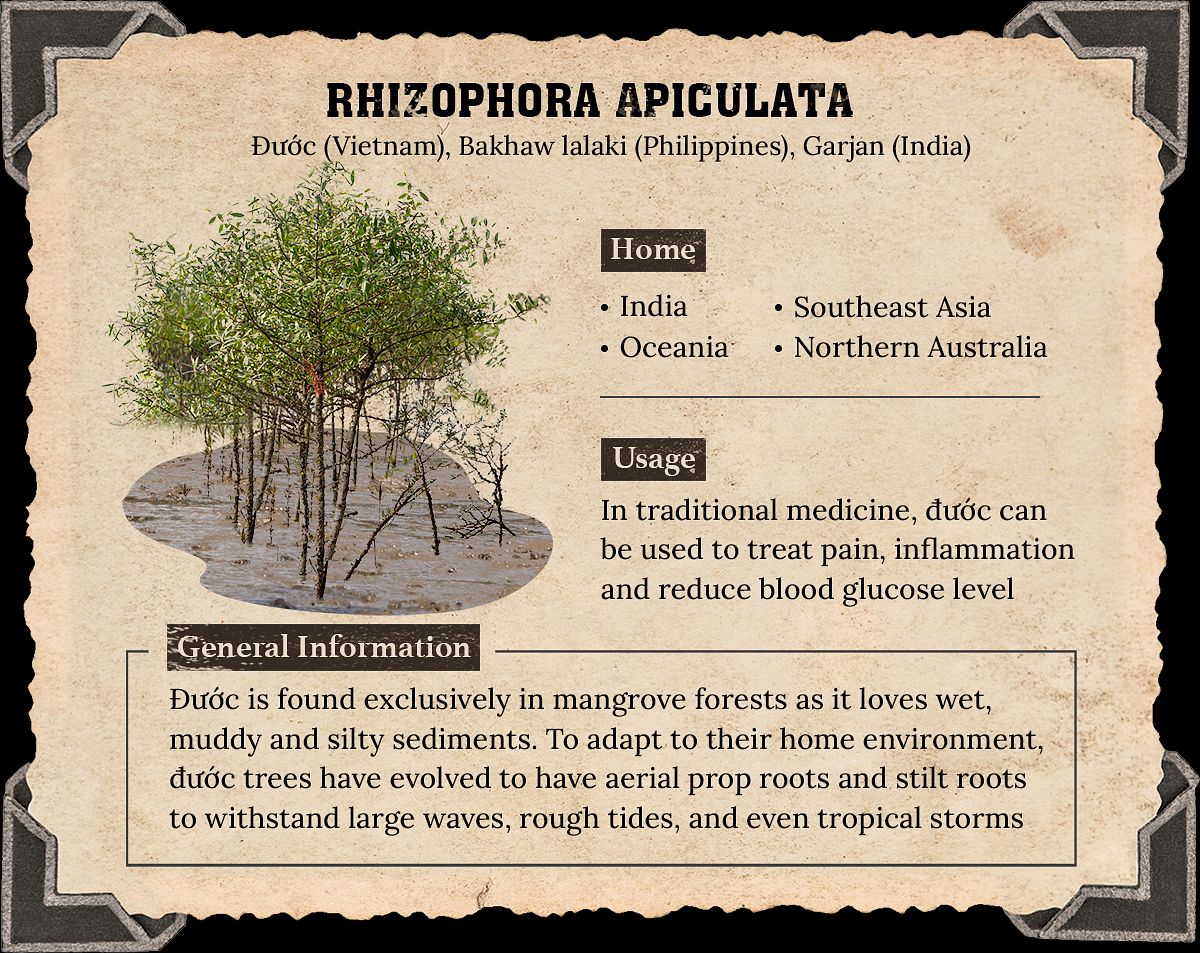

Thực vật ngập mặn, meanwhile, refers to mangrove plants overall, with cây đước (Rhizophora apiculata) being one of the most common in Vietnam — they feature the distinct umbrella of roots visible at low tide.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll stick with thực vật ngập mặn when referring to individual plants.

Vietnam’s Thực vật ngập mặn

Southeast Asia is home to the world’s greatest diversity of mangroves, and as a tropical country with an extensive coastline, Vietnam plays a key role in this. Extensive rừng ngập mặn can be found in Mekong Delta provinces like Cà Mau and Trà Vinh, while Saigon’s Cần Giờ is often called the city’s “green lung” thanks to its massive, UNESCO-recognized rừng ngập mặn. You can also find patches of mangroves near Hồ Tràm, Quy Nhơn and Huế, as well as all the way up in Hải Phòng and Quảng Ninh.

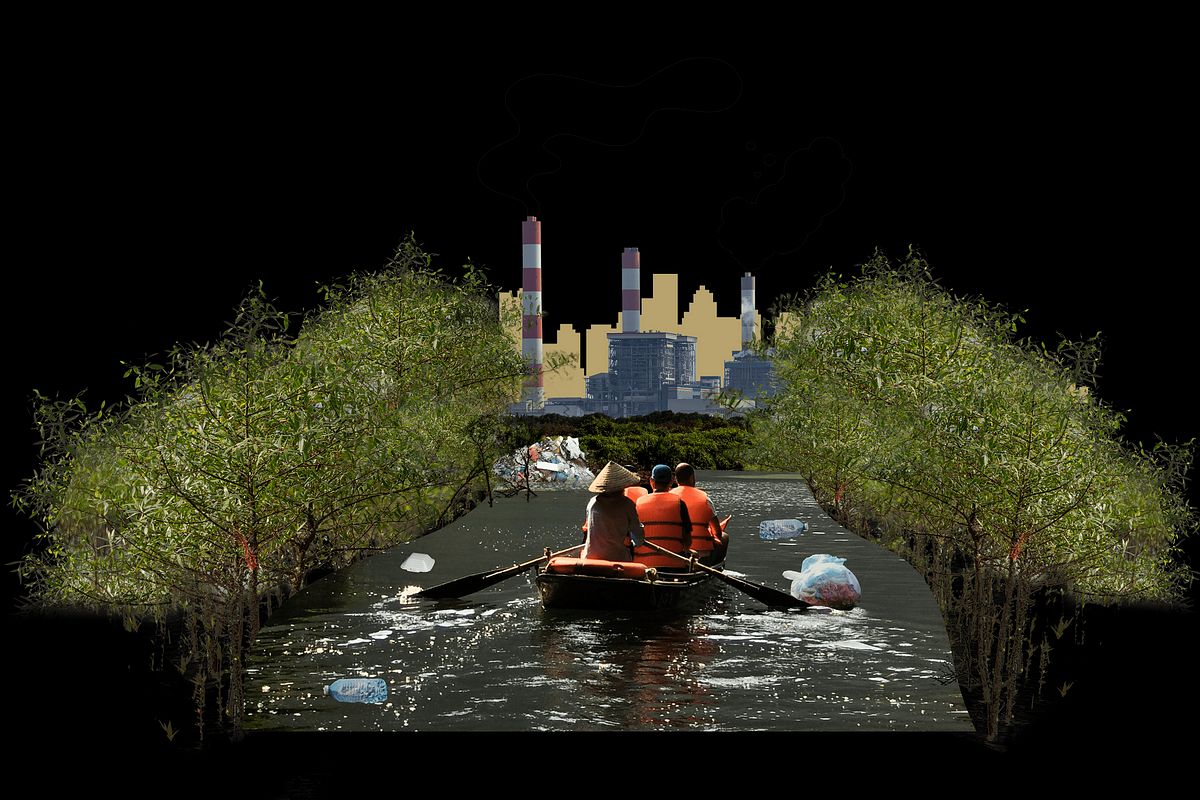

However, these mangroves are under threat, not just in Vietnam, but around the world. Their coastal habitats are often desired by real estate and tourism developers, as evidenced by ongoing discussions regarding potential developments in Cần Giờ and Cát Bà .

These mangroves are under threat, not just in Vietnam, but around the world.

A quick Google Maps search of Quy Nhơn below the Thị Nại Bridge shows mangrove areas being filled in for construction. Mangroves in southern Vietnam were also heavily defoliated by the US Air Force during the war, with Cần Giờ, in particular, being left a barren wasteland that has been rehabilitated in the following decades.

But all hope is not lost: organizations are working to expand the mangroves in both Cà Mau and Trà Vinh, and there is growing awareness of the role they can play in protecting people from sea level rise, storm surge and typhoons, while also helping to reduce the amount of carbon in the atmosphere.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme, the soil held together by mangrove roots “[locks] away large quantities of carbon…stopping it from entering the atmosphere.”

The soil held together by mangrove roots locks away large quantities of carbon...stopping it from entering the atmosphere.

Dense rừng ngập mặn can also reduce the impact of storm surge by absorbing the strength of water as it moves in from the sea. A growing body of research has found that parts of Indonesia surrounded by mangroves experienced far less damage from the catastrophic 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami compared to more exposed parts of the coast.

While Vietnam’s coast faces a minimal risk of tsunamis, typhoons and tropical storms in the East Sea are expected to get stronger in the future, exposing communities to more powerful storm surges and waves.

Thực vật ngập mặn are a 100% natural way to offset some of these future impacts. To be sure, they can’t prevent everything and are not a one-stop cure-all for areas along the ocean, but too often we ignore what the world has given us in the race to embrace new technology.

Dense rừng ngập mặn can also reduce the impact of storm surge by absorbing the strength of water as it moves in from the sea

And this is just on the human side: rừng ngập mặn are also crucial for biodiversity, harboring scores of species both on land and in the water. Bulldozing them leaves these animals with nowhere to go, at a time when inland forests are also being relentlessly cleared in the name of human progress.

I would argue, then, that it’s time to reconsider how we think about the coast. Beaches and ocean views are certainly nice, but they can’t be everywhere. Thực vật ngập mặn may be a literal stick in the mud, but we’re in trouble without them.

Thực vật ngập mặn may be a literal stick in the mud, but we’re in trouble without them.

The author in Tra Vinh’s mangrove forest.