From the time I began learning Vietnamese at home and English in public school, I have lived with dual identities pulling me from seemingly opposite ends of a spectrum.

Refugee and American. Lower and upper class. Aid beneficiary and development professional. These identities have been kept in separate worlds, split down by the languages spoken and names used. At home, I answered to my Vietnamese name, Loan, the filial daughter who aspires to pull her family out of poverty in America. To the rest of the world, I was Kim, the USC graduate, professional businesswoman come development professional traversing the world. Throughout my life, I had been forced to compartmentalize these identities, code-switch and compete for limited resources within my own self and the world around me. However, living in Vietnam has shown me the true strength of navigating these dualities and the power that lies in living as both Kim and Loan simultaneously. Vietnam has accepted me in my entirety, allowed my identities to bloom, integrate and unapologetically flourish.

Loan grew up watching her mother, who dropped out of high school to flee persecution in Vietnam, clean people’s hands and feet every day to keep food on the table in America. While I grew up in poverty, I learned to love my Vietnamese heritage dearly. To me, being Vietnamese meant sharing rooftops with cousins when we first moved to America, or sheltering the families that came after us. Being Vietnamese meant the most delicious cuisine in the world was served on my dinner table daily, the language we shared at home became the backdrop to my life, and my imagination was woven by stories my grandparents brought from the motherland.

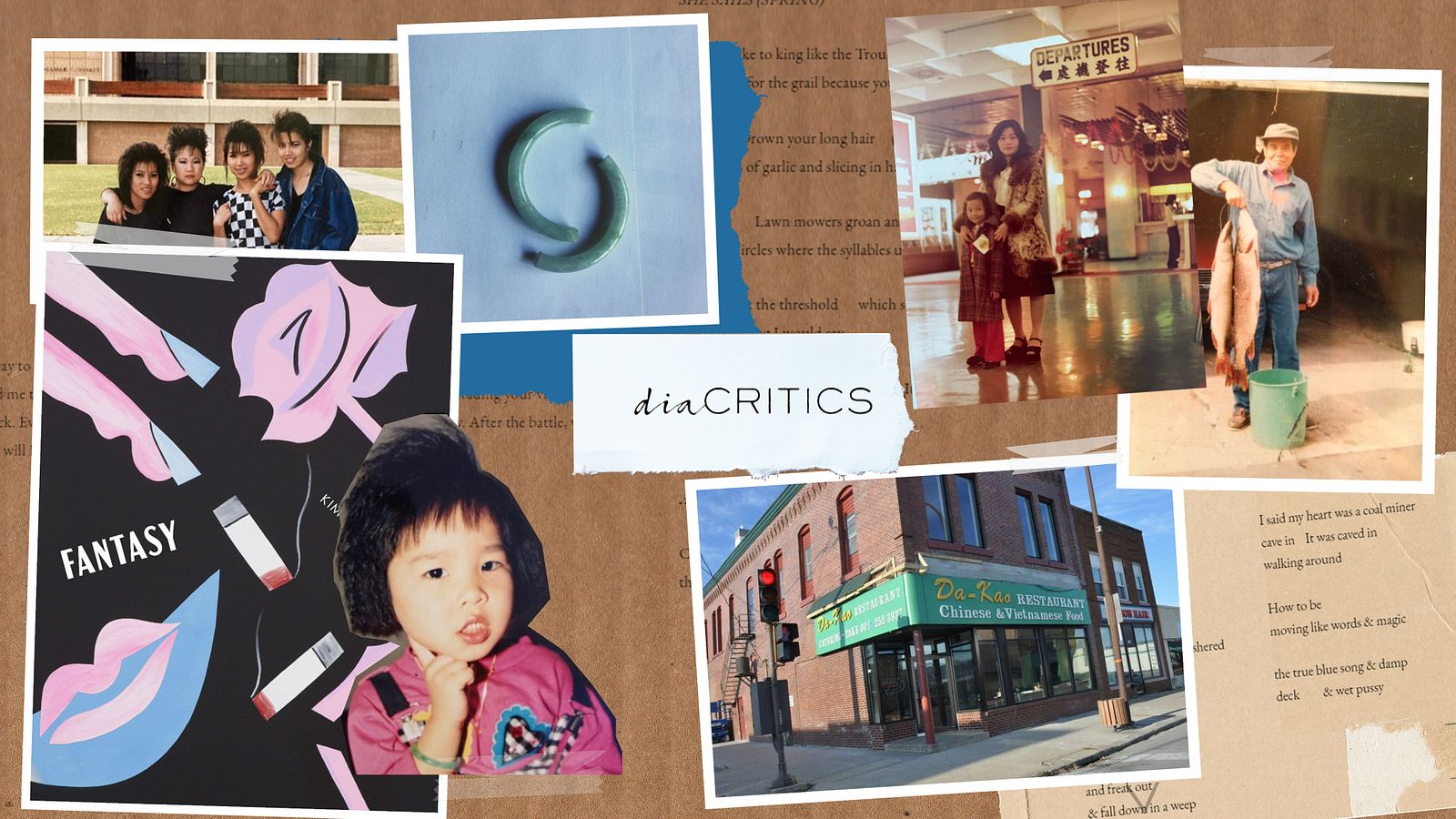

Kim Loan holding her name card at Sikiew Refugee Camp.

However, I was also conditioned to hide my Vietnamese identity — Loan — from the outside world. As I entered kindergarten, my mom had me go by “Kim” in school so others wouldn’t have difficulty pronouncing my name. After being teased for my Vietnamese accent in grade school, “Kim” stayed in English as a Second Language programs for years until all traces of an accent had vanished. I loved Vietnamese food, but refrained from packing it for lunch, as my classmates found the Vietnamese staple, fish sauce, unappetizing. The daily code-switching became a part of my routine and I poured myself into what I saw as the gateway out: my education. This was my ticket out, and I truly believed that the moment I graduated from university, our family’s poverty cycle would finally break. And it did for a brief moment. Upon graduation, Kim landed a dream job as a management consultant, flying around the country working on interesting business problems while supporting her family.

Shortly after, however, Loan’s family life became a nightmare devastated by divorce, addictions, and critical physical and mental health issues dragging the entire family into homelessness. When a family lives paycheck to paycheck in America, one wrong turn can lead to a slippery slope. Two wrong turns, and the façade of security can completely shatter.

Throughout my early twenties, I stepped up as the head of the household for a family fighting extreme poverty, while simultaneously working for executives in the top one percent. Kim was flying cross-country during the workweek to help Fortune 100 companies with their growth strategies, and Loan returned to Virginia on the weekends, where her parents were living in doorless rooms, battered vans, or empty sheds. Amidst these tumultuous times, I found both Mom and Dad homes, served as their therapist, guided them to community health centers, helped my little brother get into college, and everything in between. Every week, I shifted between these two strikingly disparate identities and used the weight of my body, mind, and heart to hold these worlds together.

This experience fuelled my desire to understand my parents’ psychological, socio-economical, and cultural inheritances from Southeast Asia while using my skills developed as a consultant to address the structural inequalities leaving others in this region in poverty. Loan retraced her family’s emotional and physical journey back to the Thai refugee camp where she was born and found the irrefutable imprint it left on her family’s socioeconomic background and predetermined trajectory in life. Kim, on the other hand, was able to use her skills and experiences to be more effective as a development professional, but the challenges of being a woman of color — not “actually American” but not “Southeast Asian enough” either — infiltrated daily life. Emotionally exhausted, isolated, and recognizing that I was tapping into the scarcity mindset, my heart yearned to continue this journey in Vietnam.

It felt risky to move to Vietnam without a job, especially with the weight of my family’s stability in America on the line, but I took a leap of faith and trusted my gut that this was where I needed to be at this time. In hindsight, my gut was 200% right, I landed my dream job in two weeks, and I found my wings in Vietnam.

From the get-go, I was blown away by my ability to hear and understand all the daily life around me, in contrast to life in Laos, where I was limited to my English and basic Lao language skills. Having seldom used Vietnamese outside of my home in America, Loan’s Vietnamese was confined to the vocabulary used at home with family. But in Vietnam, her world expanded as she made new friends in Vietnamese, naturally introduced herself as “Loan” to strangers on a daily basis, expressed herself in both formal Vietnamese and slang, and learned to read and write in her native language. Loan was no longer just a daughter and granddaughter, but a friend, professional working woman, traveler, Việt Kiều (foreign-born Vietnamese) living in Saigon, and language student. Loan’s journey of coming from a refugee camp, growing up in poverty and resilience, was not only heard, but seen. After sharing my reflections of the impact the refugee experience had on me, I was blown away by a wave of friends all over the world thanking me for sharing my experience. However, I was also grounded when my Vietnamese aunt stated that she had read my piece. “It was beautiful,” she said, “but also a story we all know in this country.” She didn’t mean it as a backhanded compliment, rather to state that she understood it very well. Perhaps too well, unfortunately.

Similarly, Kim no longer felt the pressure to hide any part of her identity as Loan from her communities. While sharing her background as a former refugee or coming from poverty was often met with discomfort from professionals and friends in America, it was met with empathy, compassion, and curiosity in Vietnam. The skills and experiences Kim and Loan brought from America were celebrated. I weaved through life as Kim and Loan seamlessly as I sang Vietnamese pop songs, shared stories with locals, and hosted book clubs discussing works of Asian diasporic authors.

While switching between my identities as Loan the Vietnamese refugee and Kim the American professional has sometimes been an emotionally draining, isolating experience, I have grown to become creative, resourceful, resilient, and empathetic as a result of navigating the in-between. The duality that I’ve tried to compartmentalize throughout my entire life has now become my greatest source of strength. I originally wrote about bridging these identities in my graduate school essays from my time in Laos, but little did I know that was only an ounce of what it felt like in Vietnam. After moving to Saigon, I feel it through every bone in my body. My Vietnamese language ability, groomed by my late grandparents, allowed me to internalize locals’ words spoken and the ones left unspoken. My lived experience as Kim and Loan was not only understood, but seen as a strength.

About a year and a half ago, I shared with a colleague that I was thinking of legally changing my name from “Loan Kim Chu” to “Kim Chu” to avoid confusion and simplify my name for others. For one, no one knew me as Loan outside of my family, and I would always change my alias to “Kim” anytime I joined a new organization anyway. While I liked the ring of “Loan,” people often messed up its pronunciation or the Vietnamese pronunciation of Loan could be so daunting to those not used to foreign names that they’d be too embarrassed to try pronouncing it. It would’ve been simpler to be “Kim Chu.” However, after experiencing the life as Kim and Loan (and sometimes Kim Loan) in Vietnam, I cannot imagine erasing any of my names for the comfort of others.

When I was a kid, I had asked Mom for the meaning of my name. She replied that “Kim” meant gold and “Loan,” for lack of better Vietnamese words, was a “beautiful bird.” I always thought she meant swan, but when I asked a Vietnamese friend for clarification a few months ago, she told me that “Loan” was a less commonly used word for “Phoenix”… My parents named me after a golden phoenix, and I nearly erased the wings out of my name for the comfort of others!

No, not this time.

I may have arrived in Vietnam as two disparate identities — Kim and Loan — but I’ve left as the golden phoenix my parents originally intended for me: Chu Kim Loan.

Kim Loan was born in a refugee camp in Thailand and was later resettled in the US. A student of the world, Kim Loan is passionate about refugee aid, women’s empowerment, and digital inclusion.

This essay originally appeared in diaCRITICS and has been republished with permission as part of an on-going collaboration between Saigoneer and diaCRITICS.