“Vietnamese communities can sometimes/often demand conformity and tradition of people in order to feel a part of things; I have always seen diaCRITICS as an opportunity to trouble the definitions, push the boundaries, to include the atypical voices and stories and viewpoints.”

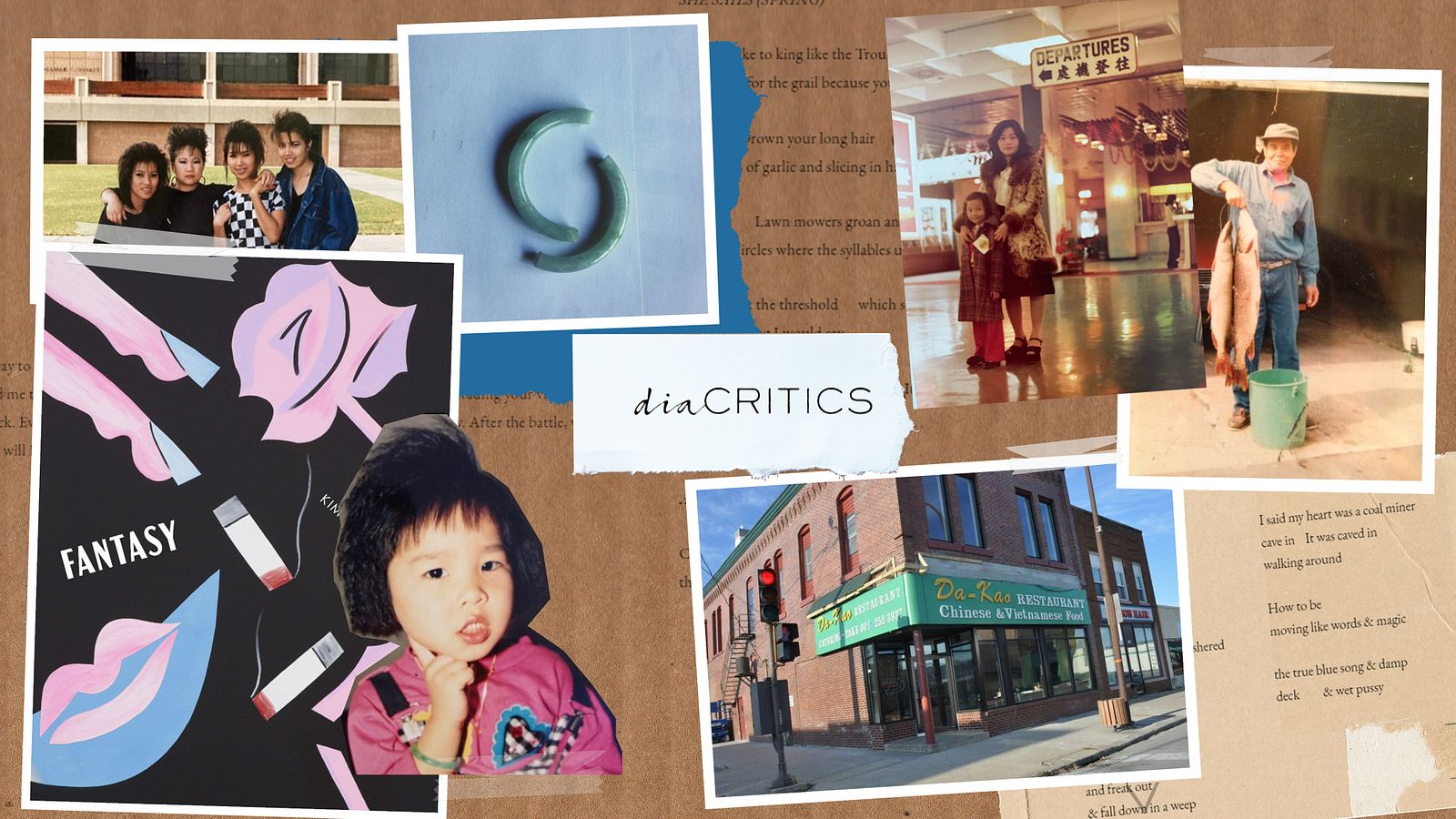

This statement, offered by Dao Strom, outgoing editor-in-chief of the online publication diaCRITICS, serves as a fine introduction to the online publication that has been an important platform for diverse diasporic voices in fiction, poetry, non-fiction, photography, visual art and filmmaking.

Saigoneer has long championed the US-based publication, sharing its articles on our social media platforms to great popularity. We had the opportunity to meet Dao in person during her visit to Saigon last year, which resulted in a more concrete partnership in which we re-publish some diaCRITICS articles directly on our site. While Saigoneer generally focuses on people, places and topics within Vietnam, we share diaCRITICS’ aims to amplify the ideas and encounters of Vietnamese around the world and bring attention to stories of and about Vietnamese identity and experiences.

Origins and Evolution

A photo from the 2017 “Vietnamese Londoners” exhibit founded by Julia Thanh, the first photography exhibition dedicated to the British-Vietnamese community.

diaCRITICS is the publication platform for the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network (DVAN), which was founded in America in 2007 in response to the lack of Vietnamese representation in academia and popular culture. It disseminates news, holds writer retreats and exhibitions, publishes books and, most recently started Accented: Dialogues in Diaspora, a virtual series of programs that brings together a variety of writers, poets, artists, actors, filmmakers, scholars, and other cultural producers from the Vietnamese and Southeast Asian diasporas for discussions.

Viet Thanh Nguyen talks with Phuc Tran as part of DVAN's Accented series.

When acclaimed novelist and scholar Viet Thanh Nguyen co-founded diaCRITICS, he was not yet a household name. Receiving the Pulitzer Prize for his brilliant novel, The Sympathizer, thrust him into the national spotlight. While the fame elevated his voice and allowed him to bring attention to important issues related to the Vietnamese diaspora, it also left him with less time to manage diaCRITICS. Thus, in 2018 he placed Dao Strom, an accomplished author, artist and musician who had been with the publication for years, in the editor-in-chief position.

While respecting its founding spirit, Dao intended to leave her own mark on the publication. She explained to Saigoneer that she tried to “add in more of [her] own lens: hybrid work, experimental, more pieces by and about women, experimental, queer, and other 'less traditional' perspectives.”

Scanning the first pages of the site makes clear how diverse the diaspora is that they feature. One encounters an interview with Elizabeth Ai regarding her upcoming film about the popularity of Vietnamese new wave music; an examination of the Vietnamese community in New Caledonia; reflections on what it means to be Vietnamese in a personal essay by Y Vy Truong; and an excerpt of an autobiography of a woman born to an unknown French father and a Vietnamese mother who grew up in Indochina and Vietnam.

Dao Strom.

In addition to welcoming more unconventional or marginalized work, Dao sought to revise diaCRITICS’ rhetorical positioning. Viet Thanh wrote on the submissions page: “Watch out. We reserve the right to be angry, to be discerning.” And while Dao has left the wording on the site to honor its original vision, she clarifies: “When I consider what I know and have experienced of being Vietnamese, even of how the older generation has explained to me our history of fighting, etc., I begin to see that the pattern of anger > fighting > resistance > revolution has long been a part of the Vietnamese psyche, and, by consequence, has also led us to the recurrences of division, exclusion/exclusivities, and disharmonies that we have weathered at multiple times in our history. So, anger is an important starting emotion for diaCRITICS, yes, and it is and has been needed in the many fights for social justice that are occurring, but I also in my editorship wanted to introduce an advocacy for tenderness, for writing from and toward love, for nurturing an expectation of inclusion that might help us also to build something new on the other side of anger’s accomplishments.”

This tenderness comes across particularly strong in the Out of the Margins series that allows creative writers to share small, personal moments of vulnerability and compassion. They lament the challenges of isolation, conflicted notions of identity and how families are often situated at the intersections of tradition, history and modernity, while also celebrating how these elements combine to challenge the notions of what it means to be Vietnamese. For example, Tony Ho Tran details the role his family’s Vietnamese restaurant had in his childhood; Anh-Hoa Thi Nguyen addresses her father with a series of “Dear Ba” letters that reveal how refugee experiences and immigration affects different individuals in different ways; and Diana Khoi Nguyen weaves biology, mythology, sociology and family in the stunning poem 'Đổi Mới'.

'Dyke Cabbage' by Vi Khi Nao which accompanied her poem 'Sapphở'

The Next Chapter

The beginning of 2021 seems an appropriate time to write this piece on diaCRITICS as they are again undergoing leadership changes and the DVAN website recently introduced a redesign. In October, Dao relinquished daily responsibilities to devote more attention to other projects including her writing, singing and visual work and She Who Has No Master(s), a collective of female diasporic writers. In addition to allowing her to more effectively pursue other creative endeavors, the transition will benefit the site because “It’s important to keep holding open the diaCRITICS curatorial/editorial leadership to others — it has always been that diaCRITICS is meant to be a collective space, a space containing and created by many voices and many fluctuating currents and interests.”

Regular readers of diaCRITICS will be familiar with the person taking up the mantel in Dao’s absence. Eric Nguyen began reviewing books for the site in 2012, and his insightful, contextualizing essays led to him becoming the Books Review Editor. Such a literary background explains his hopes to push "avant-garde writers, but at the same highlighting the spaces where Vietnamese diasporic people are often not given the chance to give their voice. I'm thinking, for instance, of genre fiction written by Vietnamese diasporic writers, opinion pieces on issues that are usually not given a Vietnamese diasporic voice (like racial inequity and police violence or climate change). Vietnamese diasporic people are already out there doing this stuff as artists, activists, and leaders. I envision diaCRITICS being a space where these voices are front and center."

Eric Nguyen.

diaCRITICS serves as a helpful introduction to some of these less-prominent writers deserving of attention. Eric adds: “There are many great Vietnamese diasporic writers working. Among all the wonderful work being published, I would recommend the poetry of Hieu Minh Nguyen, whose writing explores the queer experience in powerful and captivating language, and Hoa Nguyen, whose work is a joy to read. For prose, I'd recommend Kim-Anh Schreiber, whose book Fantasy is a hybrid work that is part film criticism, part narrative, part drama; and Kevin Nguyen, whose novel New Waves goes beyond what readers typically expect when they talk about Vietnamese-American literature.”

This focus on less-predictable literature that diaCRITICS aims to champion is essential because, even though high-profile works by authors like Ocean Vuong, Thi Bui and Phan Nguyen Que Mai, have been major achievements for the community, much progress remains needed. As Dao notes: “‘High profile’ success is a win, so to speak, in terms that in a best-case scenario it means it opens the door, or at least puts a toe in the doorway, for other Vietnamese American writers and other types of Vietnamese American stories — hopefully not just war-related ones — to also become validated by 'the establishment' and be seen as worthy of interest to a wider, more 'mainstream' swath of readers. I think these are all positive steps and advances along the way, and the landscape is slowly, ever so slowly, changing in America for many writers of color and marginalized groups. However, I also see some dangers in lauding these achievements and lionizing them. First, I’ll say: why do we care — why do we want and aspire to — recognitions of a 'high profile' i.e. major awards vs publication with, for instance, well-reputed small presses who are also doing valuable publishing work? Or, why do we need to wait for a book to receive validation from an establishment award, for us to recognize its merits? I also see that the most widely recognized (by mainstream outlets) works by Vietnamese authors still largely display certain markers to make 'legible' our existence or worth: as either victims and/or survivors of war, refugee-hood, trauma, etc. These are very true elements, of course. Yet the focus on them reflects an 'American' gaze that still defines the 'Vietnamese' person in terms of wounds.”

As with many communities, the relationship between Vietnamese in Vietnam and those abroad can be fraught. The divides can lead to people not wanting to converse with those outside of their perceived identity. Assumptions, prejudices and opinions arise, in part, from a lack of dialogue, and this fractured communication makes it difficult for empathy to take root. It’s within this context that outlets like diaCRITICS are vital.

As Dao explains: “There are many divisions — in my experience — inherent in our being Vietnamese and especially as Vietnamese in the diaspora. There is a long 'pattern' of divisions and divisiveness, questions of who belongs or who doesn’t, who is 'more' truly Vietnamese or not (due to geography, familiarity or fluency of language, customs, etc), and — in some cases — degrees of animosity and ideas of inclusion/exclusion persist. As a writer and as a Vietnamese person who has long felt the psychic loss embedded in our narrative, I am also interested in transformation and healing and becoming cognizant enough of those 'patterns' to not fall prey to them in the unfolding future…these are some of the reasons why I feel it is important to reach across the divides of our 'Vietnamese' (diasporic and native) experiences, to try to reconnect and listen to all the different stories, from different shores. In my simplistic thinking, this is the path to a new way of being/defining what or where or who defines what it means to be Vietnamese. My hope, which reflects also the hopes and mission of diaCRITICS and DVAN, is for dialogue between Vietnamese all over the world, in Vietnam and in the diaspora, so that we can enlighten one another and transcend the boundaries and divisions that 'state' and 'national' and 'historical' narratives have ingrained.”