it took me till my college years when saying “I love you” became a normal thing

these moments would take place during weekly phone calls with my parents

I guess the heart does grow fonder with distance

and as distance grew,

the more often we sent these three words to each other over the phone

the more we opened up to each other

– crossing oceans has been the loudest I’ve been with them

funny how asian parents show their love

of course, as our daily homecoming greeting, they’d ask, “con ăn cơm

chưa?”

because it was the hearty presence of food, not scarce displays of soft love

that filled their hunger – and hence, a generation gap was formed

my cousins and I would get mad at our parents sometimes constantly asking us if we ate yet

why couldn’t they ask us how our day was instead

or whether we’ve made a move on our school crushes yet

like how awkward other american parents do it

we became numb to their question, answering almost robotically

“con ăn cơm chưa?”

“dạ ăn rồi.” | ”have you eaten yet?”

“ăn rồi.” | I have.

“ăn rồi.” | I have.

I currently work at a vietnamese restaurant on lygon street in carlton, australia

neither my parents or I would have expected me to work in the service industry after college

but this is 2019

although I kept my job a secret from my parents for a while

it didn’t feel like I did

“why did you come all the way here to work at this dinky little restaurant? you should’ve stayed in america where your life was probably better there than it will be here.”

“I’m on a work and holiday visa. I’m here because I want to travel the world.”

like my parents, the adults at the restaurant would shake their heads in frustration and disapproval, never understanding the decisions that I’ve made

my parents fought so hard for a life better than theirs for me

“we took up low-paying jobs, learned a new language, and moved to another country for you.“

their words would continue to echo in my head

as I washed dishes and

swept and mopped the wooden floors of đông phương vietnamese cuisine

the irony of reliving my parents’ struggles in oz

(except my struggles were nowhere near theirs)

with the help of my iphone, google translating phrases from english to vietnamese

life became a lot of relearning of what I’ve unlearned as a child

I worked 30, 40, sometimes 50 hours per week at the restaurant,

never expecting much in return except for experience and a paycheck

I wasn’t there to bond with my vietnamese roots, really

but I never felt so much rooted since my separation years in college

an uncle would come in and ask me to write up a paragraph of the latest chef’s specials

so I felt very fortunate to be able to write in our language when he asked

he’d point out my misspellings

and I’d have to reassure myself that they didn’t make me

any less of my parents’ child

the menu:

phở bò for $11 | beef pho for $11

bún bò huế for $12 | spicy beef noodle soup for $12

bún riêu for $12 | crab noodle soup for $12

bánh xèo from $14 | vietnamese crepes from $14

chả lụa for $8 | vietnamese pork sausage for $8

and the list goes on with 400 more items

eventually, all of that reading ended up making me feel hungry

and I wasn’t the only one thinking that way

suddenly, I would be bombarded by the same question I’ve heard for years growing up

but coming from different voices now

“chị ăn cơm chưa?”

“em ăn cơm chưa?”

“cân ăn cơm chưa?”

my heart is full.

Jessica Nguyen/Nguyễn Thị Mai Nhi is a world traveler, activist, and writer. To learn more about her current projects, please visit her website at byjessicanguyen.com or follow her @byjessicanguyen on social media.

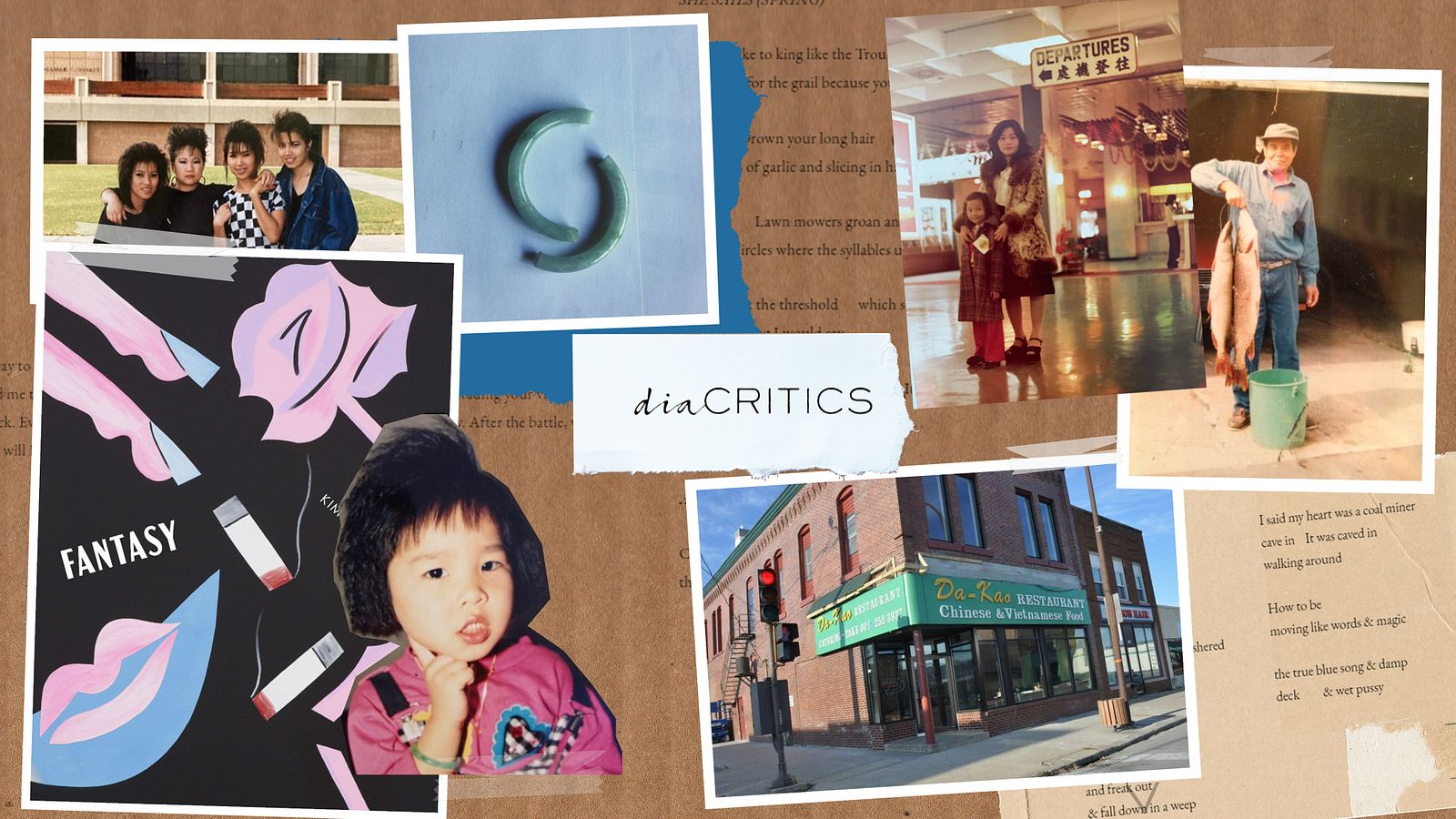

This poem by Jessica Nguyen originally appeared in diaCRITICS and has been republished with permission as part of an on-going collaboration between Saigoneer and diaCRITICS.