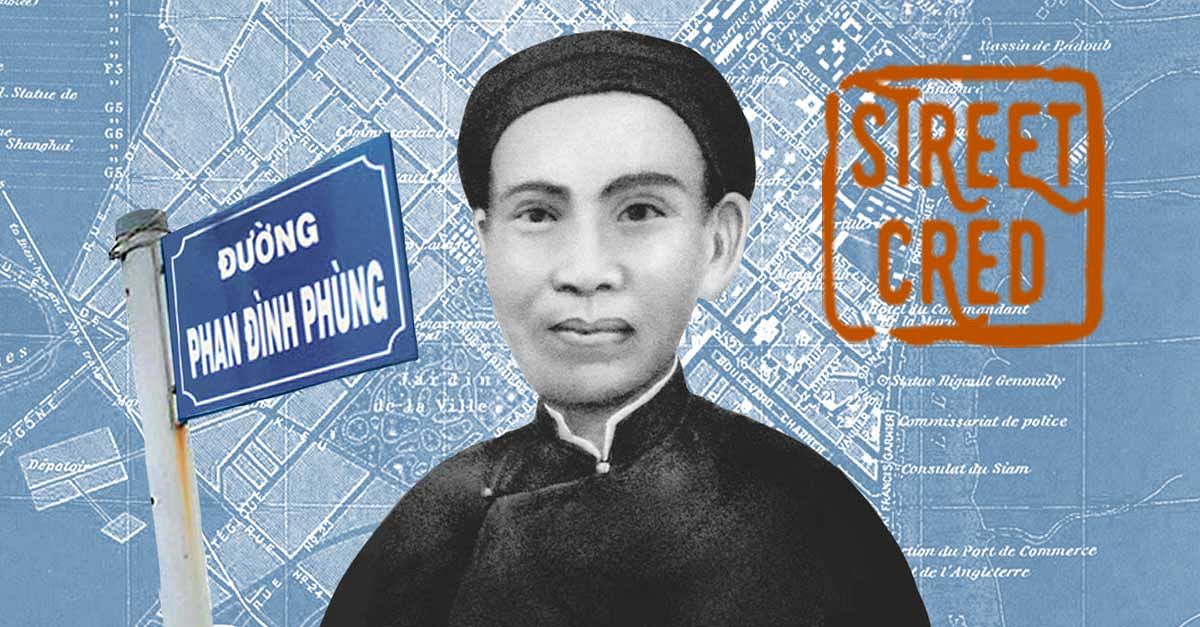

An unassuming street named Phan Đình Phùng runs through Saigon’s Phú Nhuận District. It is named after a Vietnamese revolutionary who led rebel armies against French colonial forces in the 1880s and 1890s. He is also my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather.

In 2019, while on his deathbed in Nha Trang, my grandpa, Phan Dinh Dien, informed me that we were descendants of Phan Đình Phùng, and we, therefore, needed to do what we could to make Vietnam a better place for all.

I’ll start by making a little bit of history more accessible:

Phùng was descended from 12 generations of bureaucratic scholars, but while no dummy, it was his integrity and uncompromising stance against corruption that he was known for, not his scholarly abilities. He rose through the ranks under Emperor Tự Đức’s reign, calling out many incompetent and corrupt fellow bureaucratic scholars, including the viceroy of northern Vietnam and the foremost scholar of the court, Tôn Thất Thuyết (his street sits in District 4).

In 1883, the childless Emperor Tự Đức refused to appoint his most senior heir, Dục Đức, having written in his will that Dục Đức was depraved and unworthy of ruling the country. He instead named his nephew, Kiến Phúc, as his successor. Unfortunately for Emperor Tự Đức and Phan Đình Phùng, Tôn Thất Thuyết (the scholar who was previously criticized by my ancestor), was appointed administrator of the country. True to his dishonest ways, Thuyết ignored the late Emperor Tự Đức’s will and enthroned Dục Đức.

My grandfather, Phan Dinh Dien, on the right.

And, true to his principled ways, Phùng protested and refused to recognize Dục Đức’s authority. According to Hue-Tam Ho Tai’s book Radicalism and the Origins of the Vietnamese Revolution, Phùng only narrowly escaped the death penalty for his insolent behavior because he was so widely admired by the other regents. He was, however, stripped of his titles and exiled to his native village back in what is today Hà Tĩnh Province.

Meanwhile, back at Huế's royal court, Thuyết was orchestrating plenty of turmoil: three emperors were deposed and killed in just over a year. In 1884, 12-year-old Hàm Nghi was enthroned as the Emperor of Vietnam.

Being literally a boy, he was easily and quickly dominated by Thuyết and his associate, Nguyễn Văn Tường. At this point, the French were gaining power around Vietnam, and with this latest succession, concluded that the two regents were causing too much trouble, and sought to remove them.

Tensions erupted on July 4, 1885 when Thuyết and Tường organized an attack against the French. Things didn’t go as planned, and French forces ended up capturing the imperial palace and looted it out of anger over being attacked. On the heels of the defeat, the imperial court fled Huế. Thuyết took the teenage Emperor Hàm Nghi and three empresses into hiding at a mountainous military base near Laos. From there, the regent Thuyết convinced the now-13-year-old king to issue a proclamation calling for the Vietnamese people to rise up and "aid the king" (cần vương). Thus, the Cần Vương rebellion against French colonial rule had begun.

Phan Đình Phùng Street in Đà Lạt.

This is where Phùng comes back into the picture. He was all for overthrowing French colonial rule and re-installing Hàm Nghi as emperor. He joined the Cần Vương movement by creating his own guerilla army and setting up bases in his home province of Ha Tinh.

Phùng's first notable attack targeted two nearby Catholic villages that had collaborated with French forces. Unfortunately, the attack was unsuccessful, and French forces quickly overwhelmed them, forcing a retreat. And in a crazy twist of fate, the former viceroy of northern Vietnam — the same one who had been removed from his imperial position because Phùng called him out as incompetent and corrupt — was now a French collaborator and governor of of neighboring Nghệ An Province, and ended up capturing Phùng’s brother during the attack.

The French then convinced one of Phùng’s old friends to beg him to surrender in order to save his captured brother, his ancestral tombs, and his entire village. According to Radicalism and the Origins of the Vietnamese Revolution, the French also offered to award Phùng a high colonial government position if he agreed to work with them. His pithy response: "If anyone carves up my brother, remember to send me some of the soup."

So the French arrested his family and desecrated the tombs of his ancestors, publicly displaying their remains in Hà Tĩnh.

But Phùng had bigger things on his mind than worrying about the public violation of his ancestors’ remains. In 1888, Emperor Hàm Nghi, who Phùng still wanted to re-install, was betrayed by his bodyguard Trương Quang Ngọc, captured, and deported to Algeria. This incited Phùng to come down from the north, track down the traitor Ngọc, and personally execute him.

All this mischief-making made Phùng the target of Hoàng Cao Khải, the French-installed viceroy of Tonkin who, being of the same scholar-gentry background and village as Phùng, recognized him for the true threat he was. They exchanged a series of letters in which Khải pleaded with Phùng to surrender and end the Cần Vương rebellion in order to stop the prolonged suffering of their countrymen.

Phan Đình Phùng Street in Buôn Ma Thuột.

Khải promised he would lobby French officials to pardon Phùng if he were to surrender. Phùng refused, citing Vietnam’s impressive resistance against China, a neighboring country “a thousand times more powerful” that has “never been able to swallow it up” and put the blame for Vietnamese suffering on the French. With this refusal in hand, Khai went to French officials and called for the "destruction of this scholar gentry rebellion."

According to Oscar Chapuis’ The Last Emperors of Vietnam: from Tu Duc to Bao Dai, in July 1895, French area commanders called in 3,000 troops to crush the three remaining rebel bases. Most unfortunately, Phùng contracted dysentery. And as any of us who grew up playing Oregon Trail knows, this now very curable disease was then a death sentence. Six months later, on January 21, 1896, Phan Đình Phùng died, and in the words of the French governor general leading the attacks, "the soul of resistance to the protectorate was gone."

But the story doesn't end there. After Phùng's death, Ngô Đình Khả, a member of the French colonial administration, had his tomb exhumed, burned the corpse, and used the remains as gunpowder to execute anti-French revolutionaries, such as Phùng’s captured followers, as described in Vũ Ngự Chiêu’s The Other Side of the 1945 Vietnamese Revolution.

In contrast, Khải, the viceroy of Tonkin who led the take-down of Phùng, was held up by the French colonial authorities as an example of true patriotism and so died with riches and honors, according to Radicalism and the Origins of the Vietnamese Revolution.

But today, there are no streets named after Hoàng Cao Khải, whereas practically every city and every provincial town throughout the length of Vietnam has a street named after Phan Đình Phùng. So, I guess he got the last word after all.

This article was written in memory of my grandfather Phan Dinh Dien, another great Vietnamese patriot.