According to a recent article in Thanh Niên newspaper, the Ba Son Shipyard – Saigon’s oldest and most important maritime heritage site, recognised by the Ministry of Culture and Information in 1993 as a National Historic Monument (Decision 1034-QĐ/BT) – is likely to be sold off to a South Korean investor for redevelopment.

The site, which has been under threat for many years and has already been partially demolished to make way for the new Thủ Thiêm Bridge, was described in the book Di Tích Lịch Sử-Văn Hóa Thành Phố Hồ Chí Minh (Nhà Xuất Bản Trẻ, 1998) as “an important vestige of one of Saigon’s earliest industries and the cradle of the working class struggle movement in Saigon.”

The shipyard’s founder was Nguyễn Phúc Ánh who, after reoccupying Gia Định in 1790, established the Chu Sư royal naval workshop in Bến Nghé (Saigon) to assemble a fleet of modern warships. Military mandarin and local hero Võ Di Nguy (1745-1801) is believed to have presided over its early development and masterminded the subsequent successful Nguyễn naval campaigns against the Tây Sơn, which paved the way for the final victory of 1801.

Nguyễn Phúc Ánh, founder of the Chu Sư royal naval workshop in Bến Nghé (Saigon).

After Nguyễn Phúc Ánh ascended the throne as King Gia Long (1802-1820), Chu Sư was expanded into a large shipbuilding facility and cannon foundry, which at its height employed several thousand workers of various professions.

In his Geography of Gia Định (Gia Định thành thông chí, 嘉定城通志), written during the final years of Gia Long’s reign, Trịnh Hoài Đức wrote:

“The Chu Sư work shop, located approximately 1 li [c 500m] east of the Citadel along the Tân Bình [Saigon] river, next to the Bình Trị river [Thị Nghè creek], is a factory which makes seagoing ships of the navy, a military workshop 3 li in length.”

During this same period, the “Xưởng Thủy” (Naval Workshop) was marked prominently on an 1815 map by Trần Văn Học.

“Xưởng Thủy” (Naval Workshop) was marked prominently on an 1815 map by Trần Văn Học.

Visiting Gia Định in 1819, American mariner John White was so impressed by the facilities of the royal shipyard that he “made frequent visits” and devoted several paragraphs to it in his memoirs, A Voyage to Cochinchina (1824):

“In the north-eastern part of the city, on the banks of a deep creek, is the navy yard and naval arsenal, where, in the time of rebellion, some large war-junks were built; and two frigates of European construction, under the superintendance of French officers. This establishment does more honour to the Annamites than any other object in their country; indeed, it may vie with many of the naval establishments in Europe. There were no large vessels built, or building, but there were simple materials of the most excellent kind, for several frigates. The ship-timber and planks excelled anything I had ever seen....

There were about one hundred and fifty galleys, of most beautiful construction, hauled up under sheds; they were from forty to one hundred feet long, some of them mounting sixteen guns of three pounds calibre. Others mounted four or six guns each, from four to twelve pounds calibre, all brass, and most beautiful pieces. There were besides these about forty other galleys afloat, preparing for an excursion that the viceroy [Le Văn Duyệt] was to make up the river on his return from Hue...

The Annamites are certainly most skilful naval architects, and finish their works with great neatness…

An early Nguyễn dynasty warship.

Cochin China is perhaps, of all the powers in Asia, the best adapted to maritime adventure; from her local situation in respect to other powers; from her facilities towards the production of a powerful navy to protect her commerce; from the excellence of her harbors; and from the aquatic nature of her population on the seaboard, the Annamites rivalling even the Chinese as sailors.”

However, the fact that the French were able to sail up the Saigon river in 1859 and capture the town with little resistance has led some scholars to conclude that after 1820, under the centralising policies of Gia Long’s successors, there was a slow deterioration in the condition of both the Chu Sư arsenal and the naval fleet stationed there.

Soon after the arrival of the French in 1859, Chu Sư was upgraded. As early as 1861, Admiral-Governor Bonard ordered the construction of a 72m dry dock, but because of difficulties encountered (due to the nature of the soil), it was not completed until 6 April 1864.

On 28 April 1864, the French formally established the “Arsenal de Saigon” which, according to P Cultru’s Histoire de la Cochinchine française des origines à 1883 (1910), initially incorporated a metal workshop, a rope-making atelier, a kiln, a carpentry workshop and a boat repair dock. The nearby Naval Artillery supplied a 10-tonne crane and set up a machine centre and forge.

A view of the Arsenal in the late 19th century.

On 16 August 1866, in order to cope with increasing demand from the French navy, the Arsenal acquired a floating dry dock made from iron and measuring 91.44m L x 28.65m W. It was supplied by Randolph Elder and Co of Glasgow, which had just delivered a similar one to the Dutch arsenal in Surabaya. Embarrassingly, according to Leon Caubert (Souvenirs chinois, 1891), this installation sank on 1 September 1881.

For many years, in the absence of a dry dock large enough to accommodate its heavy cruisers and battleships, the French navy in the Far East was obliged to rely on the British Navy’s facilities in Singapore and Hong Kong.

Finally in May 1884, additional land “between the jardin Botanique and the route de Bien-Hoa” was ceded, in order that a new dry dock facility could be built. It took nearly four years to construct and was inaugurated on 3 January 1888.

The dry dock at the Arsenal de Saigon in the early 20th century.

According to Eugène Bonhoure (Indo-Chine, 1900), “The dry dock is 168 meters long and can receive the largest ships of war, ensuring our squadrons a perfectly safe and convenient refuelling and rehabilitation point.” The French name for dry dock, “bassin de radoub,” is said to have given rise to the Arsenal’s Vietnamese name, “Ba Son.”

From the mid 1880s onwards, the Arsenal’s workshop facilities were completely rebuilt and re-equipped. In the words of Bonhoure: “The Arsenal has all the tools necessary for the most difficult repairs – there is a power hammer of two tonnes which can even forge a propellor shaft…. The new work that has been implemented significantly increases the defensive value of this installation.”

Further expansion followed the reorganisation of the French navy in 1902, which created the “Naval Forces of the Oriental Seas” under the control of a Vice Admiral, comprising 38 vessels, 183 officers and 3,630 troops. In 1904-1906, the Arsenal “received many improvements,” including new facilities for the construction of S-type destroyers and a replacement floating dock, rendering it “able to meet all the demands of the full squadron of the Far East” (Situation de l'Indo-Chine de 1902 à 1907, ed Imprimerie M. Rey). In 1906 the École des mécaniciens Asiatiques (School of Asian Mechanics, now the Cao Thắng Technical College) was set up to train its staff.

The main gate of the Arsenal de Saigon in the early 20th century.

By 1913, the Arsenal was even promoted as a “place of interest” in the Madrolle tourist guidebook:

“The Naval Arsenal stands at the confluence of the arroyo-de-l’Avalanche [Thị Nghè creek] and the Saigon river, on the site of the ancient Annamite shipyard. This property is the main base of the French fleet in the Far East and has an area of 22 hectares, including a 168 metre dry dock.

The workshops, forges and power-hammers here are used to perform major repairs and even to build destroyers. Its employees include 1,500 Annamite and Chinese workers under the supervision of specialist foremen. On the river, several warships are anchored.” (Claudius Madrolle, Vers Angkor. Saïgon. Phnom-penh, 1913)

Yet another major upgrade was carried out 1918, enabling the Arsenal to build ships of up to 3,500 tonnes. The first of these “giants of the sea,” the Albert Sarraut, was launched with great fanfare in April 1921.

The launch of the Albert Sarraut (85 metres) in 1921.

However, plans for the construction of a second large dry dock facility never materialised, and after the French government signed the “Pacific Pact” in 1922 (the Washington Naval Treaty, which limited the construction of battleships, battle cruisers and aircraft carriers by the signatories), the steady reduction in the French Far East fleet and increasing concerns about the Arsenal’s cost (by 1920 it was incurring an annual deficit of around 280,000 piastres) marked the start of a long period of decline. In the late 1920s, several attempts were made to privatise the Arsenal, but these failed, and in subsequent years, lacking investment, it became increasingly run-down.

However, the 1920s were a period of increased activity among the growing Vietnamese working class, and it was at the Arsenal de Saigon, from August-November 1925, that naval mechanic and revolutionary activist Tôn Đức Thắng (1888-1980) organised a major strike which delayed the repair of the French flagship Jules Michelet, then on its way to China. According to the book Di Tích Lịch Sử-Văn Hóa Thành Phố Hồ Chí Minh (Nhà Xuất Bản Trẻ, 1998), “The mechanical workshop at 323 road 12 in the Ba Son compound was the workplace of mechanic Tôn Đức Thắng (later President of Việt Nam from 1969 to 30 August 1980), who took part in the Revolution during the years 1915-1928.” Tôn Đức Thắng subsequently made a crucial contribution to the Revolution in the south by founding the Southern Executive Committee of the Việt Nam Revolutionary Youth League (Ủy viên Ban Chấp hành Kỳ bộ Nam Kỳ) in 1926-1927.

A ship entering the dry dock at the Arsenal de Saigon in the 1930s.

Parts of the Arsenal de Saigon suffered damage during the Allied bombing campaign of 1944-1945, but repairs were carried out in 1948-1949. In the wake of the Geneva Convention of 1954, the French fleet withdrew from Sài Gòn, and on 12 September 1956 the Arsenal de Saigon was transferred to the Republic of Việt Nam Ministry of National Defence. After Reunification in 1975 it was renamed the “Ba Son Federated Enterprise” (Xí nghiệp Liên hiệp Ba Son).

An aerial reconnaissance photograph taken in advance of the 1944-1945 Allied bombing campaign.

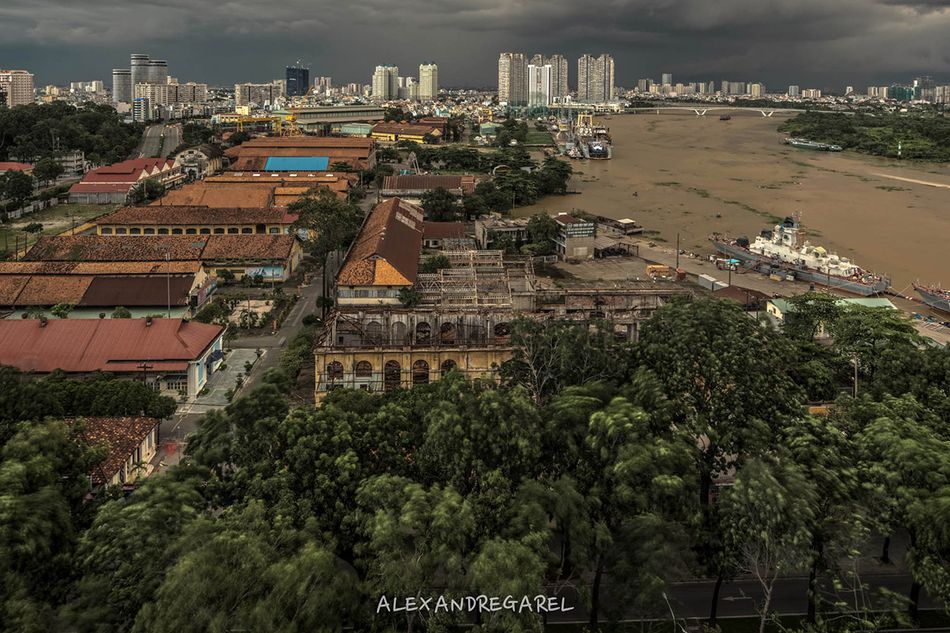

Today, the Ba Son Naval Arsenal preserves many original French workshop buildings, including several excellent examples of industrial architecture dating from the 1880s. On 12 August 1993, because of its historical, architectural and revolutionary importance, it was recognised as a national historic monument by the Ministry of Culture and Information in accordance with Decision 1034-QĐ/BT.

The main entrance to the Ba Son Shipyard today.

In the 1990s, the Ba Son Naval Arsenal Heritage Centre (Nhà truyền thống Hải quân công xưởng Ba Son) was set up outside the compound to document the history of the shipyard and its association with the young revolutionary Tôn Đức Thắng. However it was closed in around 2005 and all of its contents have since been relocated to the Tôn Đức Thắng Museum at 5 Tôn Đức Thắng.

In recent years, several travel and tourism experts have expressed the hope that the old buildings of the Ba Son naval shipyard might one day be transformed into an important leisure and heritage complex, along the lines of New York’s South Street Seaport. The latest news appears to dash all hopes that this will happen.

New York’s South Street Seaport.

Tim Russell, former Việt Nam tour operator and Thailand-based Marketing Director for luxury Asia travel specialist Remote Lands, gave his reaction to the news that the site would be completely redeveloped:

“I've been saying for years that Ba Son shipyard would make a perfect heritage zone for Saigon. The city lacks a dedicated entertainment district, and Ba Son would be perfect – colonial buildings ideal for converting into bars, restaurants, shops and cafes; city centre/riverside location; and a fully-enclosed area perfect for pedestrianisation. It would also be the perfect location for exhibits on the city's history, which is in danger of being completely forgotten in the insane rush to modernise. Sadly, none of the above is likely to happen – as usual, money will talk, the old shipyard buildings will be demolished, and we'll get more high-rise office buildings and empty shopping malls, and one of the last few drops of Saigon's charm will disappear into the river...”

Mark Bowyer, founder of respected independent travel website Rusty Compass, added:

“Ba Son shipyard is the last opportunity Saigon’s leaders have to create a downtown space of scale with a strong heritage sensibility and strong public amenity. But this isn't just a heritage issue, it’s an economic issue. Saigon’s reckless heritage destruction hurts tourism - but even worse, it hurts the city's liveability, its global brand and in turn, its long term economic interests. Heritage is no longer a niche interest for foreigners in Vietnam. Vietnamese people are now very concerned about the destruction of their city. The next generation will rue these decisions.”

Time is rapidly running out for this historic site. According to Thanh Niên the city authorities are awaiting the state government’s opinion on the US$5 billion project proposed by South Korean developers, who hope to begin work on 2 September.

Tim Doling is the author of the walking tour book Exploring Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2014) and also conducts Heritage Tours of Saigon and Chợ Lớn - see www.historicvietnam.com.