The colonial shophouse, one of Saigon’s most iconic forms of architecture, is in imminent danger of extinction.

The shophouse is a hybrid style of traditional architecture found widely throughout Southeast Asia, most notably in Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and Vietnam. It derives from traditional Asian house architecture, yet displays strong European colonial influences.

Historically, because buildings were taxed according to street frontage rather than total area, many shophouses are long and narrow in shape, similar to the vernacular “tube house.” Like the latter, they sometimes incorporate an internal courtyard or rear yard for relaxation, drying laundry or other household activities.

Shophouses are generally found grouped together in long terraces, separated from each other by masonry walls. The roofs are tiled, mostly in western but occasionally in oriental style. Façade ornamentation is varied and draws inspiration from both the eastern and western traditions.

Three-story colonial shophouse at 93-99 Lương Nhữ Học, District 5. Photo by Tim Doling.

Here in Saigon-Chợ Lớn, the earliest surviving shophouse is the one-story type with a shop at the front and a residential space at the rear. Dating back to the 1860s, the few surviving examples seem to be basic brick-built versions of an earlier local design, in contrast to the elaborate one-story colonial terraces which have survived in Hội An.

The commonest shophouse design in Saigon-Chợ Lớn is the two-story type, which also made its first appearance in the 1860s and featured a shop and storage facilities on the ground floor and residential spaces on the upper floor. Surviving examples include intact and partially intact terraces on Võ Văn Kiệt, Pasteur, Hàm Nghi, Nguyễn Huệ, Huỳnh Thúc Kháng and Đinh Tiên Hoàng streets in District 1, and Trần Hưng Đạo, Triệu Quang Phục and Hồng Bàng streets in District 5.

Two-story colonial shophouses at 26-56 Võ Văn Kiệt, District 1. Photo by Tim Doling.

As merchant communities grew in prosperity, much larger three-story shophouse buildings began to appear in clusters, with sizeable commercial spaces on the ground floor and spacious residential apartments on the upper levels. Several ornately-decorated examples from the 1890s have survived on Hải Thượng Lãn Ông Street in District 5, including the former headquarters of millionaire businessman Quách Đàm's Thông Hiệp company at 45 Hải Thượng Lãn Ông.

Three-story colonial shophouse at 43-49 Hải Thượng Lãn Ông, District 5. Photo by Tim Doling.

After the departure of the French, new shophouse buildings were constructed which combined the layout of the earlier colonial-era terraces with a wide range of modern designs.

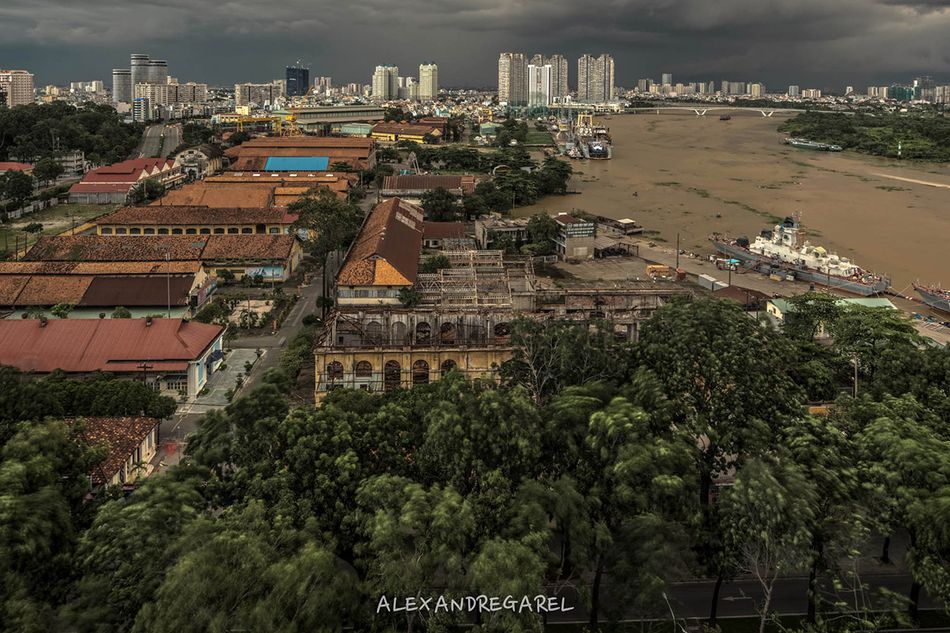

Over the past decade, lacking in maintenance and recognition as built heritage, a very large number of old shophouse buildings have been destroyed or modified beyond recognition. Perhaps the biggest loss of all was the series of elegant terraces which once lined the south bank of the Bến Nghé Creek in District 4. Sadly, the destruction is still ongoing; in recent months, five shophouses on the south side on the newly pedestrianized Nguyễn Huệ boulevard have been demolished to make way for a new shopping centre.

Like Saigon-Chợ Lớn, Singapore once had many shophouses, the majority of which were destroyed in the 1970s as the country embarked on a relentless development and modernisation drive. Not until the publication of the Wong Report of 1984 — which claimed that the disappearance of the country's built heritage was one of the principle causes of a decline in tourist numbers — did the Singapore government begin to reassess the value of its urban heritage. By that time, destruction of familiar urban landscapes, coupled with the stress of everyday life, had left many Singaporeans feeling that they had lost their roots. The government subsequently acknowledged the important role of history, memory and heritage in the making of the city, and launched a major programme to protect and preserve what remained of Singapore’s historic architecture. Today, heritage tourism plays a key role in reinforcing Singapore's image as a vibrant global city.

Singapore shophouse architecture. Photo courtesy of www.shophouses.sg.

In the words of the late first Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (1995):

“We made our share of mistakes in Singapore. For example, in our rush to rebuild Singapore, we knocked down many old and quaint Singapore buildings. Then we realised that we were destroying a valuable part of our cultural heritage, that we were demolishing what tourists found attractive and unique in Singapore. We halted the demolition. Instead, we undertook extensive conservation and restoration of ethnic districts such as Chinatown, Little India and Kampong Glam and of the civic district, with its colonial era buildings: the Empress Place, old British Secretariat, Parliament House, the Supreme Court, the City Hall, the Anglican Cathedral, and the Singapore Cricket Club. The value of these areas in architectural, cultural and tourism terms cannot be quantified only in dollars and cents. We were a little late, but fortunately we have retained enough of our history to remind ourselves and tourists of our past. We also set out to support these attractions by offering services of the highest standard.”

Among Singapore's many types of built heritage, its shophouses have provided the most flexible and adaptable foundation for repurposing as cultural, recreational and commercial facilities. Restored and renovated according to the principles of “Adaptive re-use” to meet the needs of modern life, they now house a wide range of organisations, including theatres, galleries, offices, hotels, cafés and shops. Crucially, it has been shown that property prices in areas containing refurbished shophouse terraces, such as the historic Boat Quay and Emerald Hill districts, have increased substantially in recent years — see Carl G Larson, Adaptive Re-Use, Singapore River.

In recent years, Malaysia has also sought to “develop understanding of built heritage as an expression of history and identity” (Badan Warisan Malaysia, 2004), and today it, too, encourages heritage tourism as a key component of an economic strategy which extends across the whole service sector. Refurbished shophouses once again play a central role in the lifestyles of local people and in tourism promotion — those in Melaka and Georgetown have been recognised by UNESCO as World Heritage.

Here in Hồ Chí Minh City, a balance between development and conservation has yet to be found; there is still no inventory of colonial-era buildings, let alone regulation or zoning to protect them. Consequently, the future for the city’s few surviving colonial shophouses looks very bleak indeed.

The continuing destruction of Saigon's colonial shophouse heritage: Nos 85-113 Nguyễn Huệ, pictured in March 2015 and in June 2015. To date Nos 89-99 have been demolished and others are expected to follow.

The conservation group Saigon Heritage Observatory has a series of Facebook group pages showcasing specific types of heritage architecture in Saigon-Chợ Lớn. The first of these, Shophouse heritage Saigon Chợ Lớn - Cửa tiệm mặt phố di sản Sài Gòn Chợ Lớn deals with shophouse architecture. You are invited to join this group and upload/share your own images of this rapidly-vanishing heritage.

This article was originally published in 2015.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebooks Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018), Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019) and Exploring Quảng Nam (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2020) and The Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam (White Lotus Press, 2012) For more information about Saigon history, visit his website, historicvietnam.com.