A feeble limb of cucumber supports a plastic cup filled with mango pulp. Enoki strands grow out of the orange mush, hoisting up a sheet of bánh tráng. The translucent rice paper bends, as if wilting, looking down from above.

The composite structure — seen in one of Nguyen Thi Hoa’s photographs — suggests a sense of precarious balance, achieved by a subtle interplay of its components.

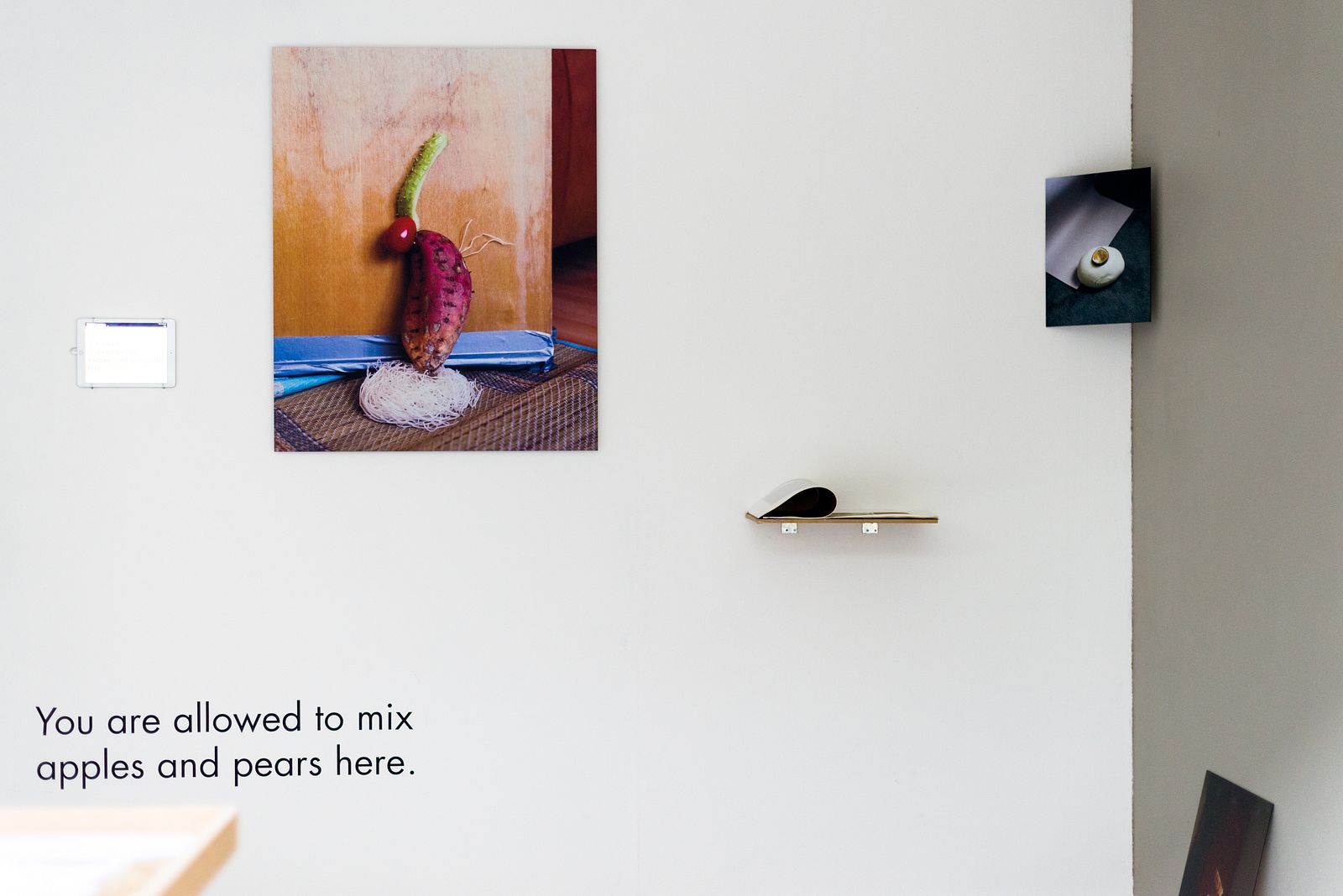

“I call my identity post-migratory because I feel like a construct of two worlds. The way that the Slovak and the Vietnamese cultures intersect in me makes me a kind of hybrid. That’s what I wanted to project into these photos — a sense of hybridity, strangeness, something indefinite,” says the photographer, speaking to me about her latest project, "You Are Allowed to Mix Apples and Pears Here."

Hoa's most recent exhibition. Photo by Nguyen Thi Hoa.

I first met Hoa in kindergarten. Although we weren’t in the same class, it was hard not to notice her, and harder yet not to be drawn in by her presence. While playing on a rusty, sand-covered swing set, she introduced herself to me as Kvetka. The traditional name, derived from the Slovak word for flower, kvet, seemed at odds with her Vietnamese roots. But she wore it proudly, explaining that it was a play on her birth name — Hoa, a blossom. At age four, she was already learning to navigate the counterpoints of her identity.

“I grew up among Slovak people. I had Slovak teachers, classmates, even a nanny. So meeting people from the Vietnamese community would be hard sometimes,” she says, wincing a little. “When talking to them, I felt like I needed to switch something on, to become more Vietnamese. But I couldn’t do it. There was so much of the Slovak in me that it didn’t leave enough space for the Vietnamese.”

At university, Hoa set out to study politics and international relations. She abandoned the course after the first year, however, daring to pursue a passion from high school: photography. Nowadays, she describes the art as her language, a tool she can use to communicate and verbalize ideas that she’d perhaps find too complex otherwise. After discovering the medium’s analytical potential, she started using photography to prod at questions about her own identity.

“When I was younger, I didn’t think too much about my parents’ migration. I knew how it happened: when [my dad came], the economic reasons, the chronology," she explains. "But I regarded it as a part of myself, something so self-explanatory and obvious that I didn’t need to deal with it beyond the sheer facts.”

Photo by Nguyen Thi Hoa.

Her father left Vietnam in 1988, pursuing the vision of a happier, more prosperous life in what was then the communist-allied Czechoslovakia, Tiệp Khắc in Vietnamese. As he slowly established himself in this strange land, selling everything from clothes to radios, traveling around the southern part of the country, he resolved to settle down in the unassuming town of Nové Zámky. Here, he reunited with his wife and first daughter, after six years of separation. In 1995, Hoa was born.

“I’m very grateful for photography,” Hoa says, pausing a little. “During my studies, I started reading more about migration. I got completely sucked into the topic and it became almost an existential issue for me,” she adds, chuckling at her own gravity. “Honestly, I doubt I could ever truly know myself, if I hadn’t gone through that phase.”

Once she cracked the topic open, Hoa dove headfirst into exploring the issues of identity, migration, and diasporas. "You Are Allowed to Mix Apples and Pears Here" combines these themes with an element that she hasn’t explored yet — food. Initially hesitant, she embraced the subject when she realized that all her questions, thoughts, and feelings could play out across this new platform.

Photo by Nguyen Thi Hoa.

"Food, like photography, is a medium of its own. At first I fought it, because I thought any photos involving food would seem too literal. But it was a university assignment and it became fascinating to see — in this huge class of students — how everyone else approached it," she says. "The works and the processes were very different, and yet, we were all bringing it back to our identities."

Food has always played a big part in Hoa’s life, even before she started exploring it via photography. A while ago, her father decided to trade a well-established clothes shop for a Vietnamese bistro. In a predominantly Slovak town, the restaurant became very successful, selling heaps of noodles, rice and spring rolls to an intrigued lunch crowd. Hoa spent many of her teenage years behind the cash register, trading quips with her cousins, who had traveled here from Vietnam to work as the kitchen staff.

“I started the project thinking about my dad’s restaurant. The food that we serve there is not completely, authentically Vietnamese," she shares. "It’s mixed, changed to reflect the Slovak environment. We sell hot and sour soup but most people buy it with a plate of French fries. That’s why I started thinking about food in terms of hybridity."

“At first, I couldn’t find a way to articulate my thoughts,” she says, recounting a creative crisis during her semester abroad in the Netherlands. Although she knew what she wanted to say, she felt that her photos lacked a certain expressiveness: “There was nothing new in the pictures. The story could’ve been told, and told better, in an article.”

Photo by Nguyen Thi Hoa.

In November, uninspired and pressed by time, she booked a quick trip back to Slovakia. That’s where, quite literally, the light bulb came on. As she opened up the fridge in her parents’ home, foraging for lunch, she was struck by an idea. She took in the contents, then took them out. Hoa started moving them about, arranging them to visualize the essence of the story she’s been trying to tell: “When I looked inside their fridge, I realized the hybridity of the things inside. And it reflected my identity perfectly.”

In her parents’ house, rice paper or fish sauce, quintessential Vietnamese staples, happily lived on a shelf next to European articles like apples or tomatoes. Her family would use primarily chopsticks, yes, but wouldn’t hesitate to grab a fork if more convenient. And when it came to cooking, Hoa realized, her own habits were growing increasingly different from her parents’ methods. She tried to imbue the photos with a little tension, to capture these newfound patterns and divergences.

In the process, she became inspired by the concept of freakabana, a still-life arrangement of mundane objects, meant to collide into an impression of strangeness and the unexpected.

“After that, my playing around suddenly had more intent. I stuck the tomato onto the sweet potato, but it was meant to look like the tomato was doing it itself, and the potato was allowing it; they met and merged," Hoa says. "In some other pictures, I couldn’t get the foods to mesh and that was alright, too, because sometimes the two things don’t go together.”

Photo by Nguyen Thi Hoa.

Looking at the photos, my eyes are first drawn to the teetering structures, analyzing the way they hold onto each other for balance. Then, they travel to the details: to the gherkin’s prickly texture and the soft curves of the bao. But for Hoa, the work wasn’t all about creating an interesting main subject.

“The structures are multiplied and accentuated by their backgrounds. They are important, too. I think that people are influenced 50% by their genes and 50% by their environments," she asserts. "And the backgrounds in the pictures are meant to show that. They are layered, textured, there’s a lack of cleanness and unanimity in them, because that’s what my own background feels like.”

By the end of December, Hoa’s photos were finished. They were printed and mounted onto a simple beige wall, and presented in a graduate show in the Netherlands. The photographer, however, decided to step beyond the personal in the project. Wanting to encourage the exhibition-goers to participate in the display, she created a website with a simple survey. There, through an inconspicuous iPad, they could detail their own backgrounds and share stories of their heritage.

A visitor interacting with Hoa's exhibit. Photo by Nguyen Thi Hoa.

“I wanted to give the project a bit more universality. The main goal was to make people identify with mine and other people’s stories, and look for the common threads rather than the differences,” Hoa says.

Aware of the communicative potential of photography, Hoa has long since decided that the message she wants to focus on in her work is rooted in empathy: “Today, it’s normal that two people from different parts of the world can come together and form a connection. By confronting them with these concrete, human examples, and making them trace their own circumstances, I hope people can open their minds a little more, with each new story that they hear.”

Before I wrap up our interview, Hoa starts passionately buzzing about her ideas for new projects. She brings up the concept of neo-colonialism, showing me a book that she’s been reading, and lists off the works that have inspired her. She talks about the artists that she’s been following recently, and reaches for a library book, pointing at some photos through the webcam. It’s almost like she’s looking into that fridge again, blinded by a new inspiration.

“Overall, I want my photography to stimulate dialogue. I don’t think I’m very eloquent but I can express myself through images. And, thankfully, I still feel like I have more to say.”

Photo by Nguyen Thi Hoa.

To see more of Hoa’s work, visit her website or follow her on Instagram @kvetnguye.

Portrait at top of page by Matej Hakar.