It is fair to say that every work carries, willingly or unwillingly, the story and life of its maker.

When I set out to interview American-Vietnamese artist Chau Diem, I expected to write about her unique and interesting artwork. During our interview, however, we found each other talking extensively about her background and her family’s history. Not only it is rare to find an individual so deeply aware and open about discussing their past but also, in Chau’s case, this is at the heart of her creativity.

Born in Vietnam in 1979 and now residing in Seattle (USA), her father’s family is originally from China while her mother’s side is Vietnamese. Her grandfather was a merchant who immigrated to Hanoi and later moved on to Saigon.

When Saigon fell, her family decided to leave their native country. The iconic photograph capturing the last American helicopter taking on board South Vietnamese has become known worldwide, but for Diem, it has a more personal connotation, since her then 15-year-old uncle Bruce Chau was one of the people on it.

“It was a big choice for him; imagine having to leave behind everything you know and your family to go to a country of which you knew nothing about. It was a very brave action on his part at such a young age. He had to decide in a very short time to risk everything and possibly never see his family again in the hope that he could get a better life in the States.

It was 1986, seven years after Bruce Chau boarded the American helicopter that six-year-old Diem and her family finally received the papers to leave Vietnam. “I remember that moment. My family had to sell everything, we only took all our photographs and cooking equipment because we did not know where we were going.

My parents were telling me that America was this magical place, but that I could not see my friends and family anymore, so for me it was like they were going to die.”

Diem’s family reached Seattle in the winter of 1986.

“Growing up quite poor, I always enjoyed drawing. I had no toys but could always find a pencil and paper. Moreover, I have always been a loner, first in Vietnam because I did not fit in due to my family being half Chinese and half Vietnamese; and then in the States because I was not American.”

Her interest in art developed at an early age, initially as a vessel to escape into her own imaginary world and later on as something deeper; “my parents were very supportive towards my art making, but only as a hobby or a passion. Like many Vietnamese, they wanted me to follow a more secure career path such as becoming a doctor or an engineer.”

The turning point in her life as an artist occurred with the death of her father:

“He was a very hard-working man who wanted to provide for his family but he also valued community work. During his life, he worked as a social worker to assist immigrants settling into American society and also collaborated with courts in translating documents from Vietnamese to English. I think he was grateful to all the people that supported my family years back when we arrived in the States and he wanted to contribute by helping others in similar situations. However, at the end of his life he was very discouraged from the, sometimes, ungrateful attitude and approach of some immigrants and the overall system. I believe that ultimately he wished he would have worked less and spent time on things that he truly enjoyed. There is a saying that I like, which goes: ‘the only things you regret in life are the things you do not do’. For me, going into arts was exactly that. I did not want to get to the end of my life and regret not doing what I loved the most for the sake of money or stability.”

Diem went on to study Art at the Cornish College of the Arts where she encountered other artists and got more actively involved in her art making by working on embroideries on silk and then moulding everyday objects, following the principle of utilizing what is available on a daily basis in a normal house.

“When I looked at art in general, I could appreciate the beauty or the skills put in it but I could not relate to it. I had an intellectual appreciation for it but not an emotional one. Many art schools can kill your emotions in favor of intellect. I wanted to go against it. You need to feel things.”

In line with this desire, she chose to begin to work with embroideries because that was what her mother did as a casual work, “I used my mother’s bowls, cups and plates to mount the embroideries. The stories were mine but at the same time, the completed piece was not too personal. People could relate to it because these common objects can resonate with many different people and anyone can attach their own memories or emotions to it.”

Diem’s artwork brings together Asian symbols, mythology, legendary stories with ordinary items: “when I worked on ceramics, I liked to create figures wearing ao dai or long-straight black hair or traditional Asian slippers. I like to keep my work minimal. I have always loved bedtime stories, myths and legends; they make the world more interesting.”

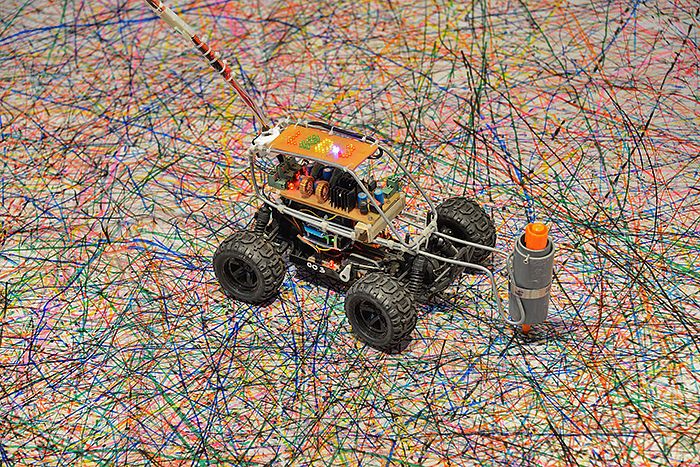

Recently she has concentrated more on developing stunning miniature sculptures, again using unconventional materials such as crayons or pencils, which she shapes with the use of a small Japanese carving knife.

“I have always been obsessed with small things. I like crayons and pencils because they are strongly linked with childhood happiness, moreover, they are both fragile. I chose to experiment with them [crayons and pencils] because I saw them as a good metaphor for childhood but also because it was very challenging to sculpt them.”

The type of art that Chau presents is quite unusual and unique, so I was interested to know how people reacted to it:

“Many people feel intimidated by art. I believe that the point of art is to connect people together. With my objects, they do not feel intimidated, actually they can relate to them because they are part of their lives. I feel there is history and spirituality in objects. I always buy used ones because they come to me with a story, a family has owned them before, only then do I add my input.”

Through the Internet, she has managed to reach broader audiences and get commissioned work from people that wanted to preserve items from loved-ones now gone.

For Chau, there is always the plan to come back to visit Vietnam where some members of her family still live, but for the moment, she is taking some time off for personal projects.