“I was in a creative writing program for grad school at the time, and I thought, as an artist, going on MasterChef would give me something to write about.”

Little did Christine Ha know that her decision to enter the American version of MasterChef, the competitive cooking show made famous by Gordon Ramsay’s acerbic assessments, would give her more than just fodder for her literary ambitions. In a sense, she was right: winning MasterChef comes with a cookbook contract and hers, Recipes From My Home Kitchen: Asian and American Comfort Food, became a New York Times bestseller.

Photo via FOX

Christine’s family is originally from northern Vietnam but they immigrated to the south, along with almost a million other northerners after the Geneva Agreement of 1954. “Because my family was originally from the north, we eat our phở the northern way with the wider rice noodles and few herbs or condiments. My grandmother was also known for her giant 8”x8” [20 cm x 20 cm] bánh chưng during Tết,” she explains.

On April 29, 1975, Christine’s father, who was still courting her mother, realized they needed to leave the country very, very soon. He rushed to ask for her mother’s hand in marriage, and they ran to find a US naval ship. Bouncing from the Philippines to a refugee camp in Guam to Pennsylvania to Chicago to southern California (where Christine was born), the family eventually settled down in Houston, Texas when Christine was two years old.

Flash-forward 18 years and Christine started losing her vision due to neuromyelitis optica (NMO), a rare inflammatory autoimmune disorder, just as she was begining to experiment with cooking. While in grad school for Creative Writing, her then-boyfriend (now husband) John Suh set up a blog. They called it The Blind Cook.

Photo via FOX

In 2012, they reached out to her about auditioning for Season 3 of the show and Christine thought the name Gordan Ramsay “sounded familiar.” John and her friends strongly encouraged her to apply so she could bring awareness to what visually impaired people were capable of. Christine simply saw it as a way to gain experience and inspiration for her writing.

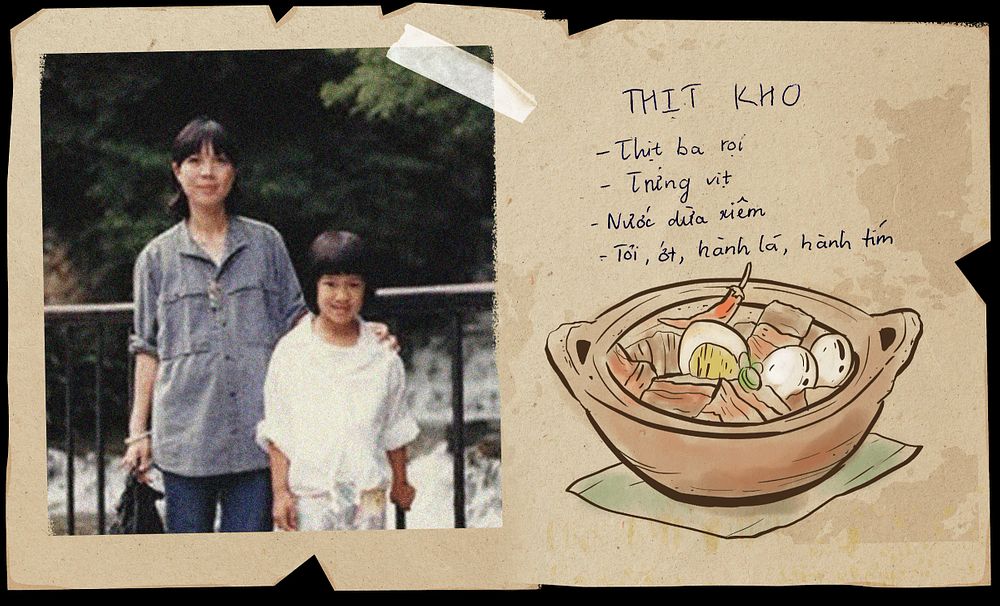

So she set aside her thesis and answered the open casting call, which asked potential contestants to present a dish that represented their life story. “For me, I’ve been on this eternal hunt to recreate my mom’s recipes,” she says. Christine’s mom passed away when she was 14 before teaching her daughter how to cook or writing any of her recipes down, so it’s been a series of trial and error since college. “I chose thịt kho because it was the dish I grew up eating the most often. There was always some in the fridge at our house.”

“I chose thịt kho because it was the dish I grew up eating the most often. There was always some in the fridge at our house.”

For her first audition in front of the judges, Christine put together another classic Vietnamese dish: cá kho tộ. Khôi Phạm, Deputy Editor of Saigoneer, reflects in a Saigoneer Podcast episode, “I think she’s one of my favorite contestants because she sticks to her roots. Her audition dish is actually a very, very traditional dish. If you watch western cooking shows, the fish is usually filleted horizontally but for Christine’s dish, she cut it vertically. If you go to fish markets in Vietnam, all the butchers will cut it that way. She doesn’t even try to deconstruct it or add any frills, bells and whistles.” A perfect balance of savory and sweet, her caramelized and braised catfish dish impressed the judges, and thus Christine’s life was changed from that point forward.

But Christine may be more familiar to Saigoneer readers for her turn as a judge on MasterChef Vietnam (Vua Đầu Bếp) Season 3 from 2015. The role made her the first former contestant to become a regular judge — in any country — and placed her amongst the few female judges in the whole international franchise. “It was a great feeling to go from contestant to the other side and become a mentor,” Christine reflects.

MasterChef Vietnam Season 1 Runner-Up, Trí Phan, reflects, “From her story, I realized the most important thing when it comes to cooking is taste. And since then, I started to put more emphasis on flavor combinations that make sense, [instead of] throwing many things on a plate, just to make it look impressive.”

The Five Fungi Congee served at Christine’s new restaurant Xin Chao. It’s a grown-up take on a dish all Vietnamese children remember eating. Photo by Tam Le.

To reference the ubiquitous Thai phrase known to anyone who has traveled to the Land of Smiles, filming MasterChef Vietnam was “same same, but different” from filming MasterChef US. “A lot of the challenges emulated the American ones, but there were still many differences. For example, the contestants cooked for the military, just like I did, but the military bases were so different. The ingredients in the pantry included a lot of fish and shellfish I’ve never heard of because they’re regional to Vietnam.” Additionally, the unionization of film crew labor in the United States meant that production could only take place six days a week, stretching filming over a period of three months; whereas Vietnam’s ability to work seven days a week meant a rigorous one-month film schedule. Same same, but different.

As a Việt Kiều, Christine faces the additional challenge of having only spoken conversational Vietnamese at home. “When I came to MasterChef Vietnam, it was terrible. Not only was there new slang, but there’s a different lexicon to speak formally on TV.” If Christine’s upbringing was anything like mine — which, as a Việt Kiều who also grew up in Houston and attended the same university undergrad program as Christine, I think is a fairly safe bet — she may have only heard this formal way of speaking on Paris by Night which has been playing non-stop at all Vietnamese family gatherings since the late 1980s.

Photo via Ngoisao.net

“As I grew older, I didn't really have family around to keep it up. So I feel like my Vietnamese [was] rusty when I first arrive in Vietnam. It’s an ordeal when I travel with my husband John, who is Korean American, but has sight. Whereas I know Vietnamese, but I can’t see. So he has to spell out all the signs, and I need to remind him to include the accents or I won’t be able to read it. But it’s like riding a bike — it comes back.”

When I asked Christine about the dishes in Vietnam that surprised her the most, she had the same answer I did when I first moved to Saigon: the new street snacks. “In America, the Vietnamese food we got was what our parents brought over [in the late 1970s], which has stayed stagnant. Now a newer generation has come up with new dishes like bánh tráng trộn and bánh tráng nướng. That’s the kind of stuff that really intrigued me.”

Creative street food dishes and nhậu culture inspired Christine and John to open their first restaurant venture: The Blind Goat (Christine was born in the Year of the Goat) in 2019. Currently located in Houston’s Bravery Chef Hall among other creative culinary concepts (there are plans to move it to a standalone restaurant), The Blind Goat is an open kitchen with about fifteen seats wrapped around it like a bar. It was the first place the public could enjoy Christine’s cooking and dishes made famous by MasterChef, such as Rubbish Apple Pie, a Pop-Tart-shaped pocket pie inspired by McDonald’s apple pies but with a Vietnamese touch of star anise and ginger in the filling and a fish sauce caramel drizzle on top.

Pork Belly Baos make the perfect fried, sweet, savory, fatty snack.

Photo by Tam Le.

It was there that Christine and John serendipitously met Tony Nguyen, chef and partner at Saigon House and their future business partner. Not long The Blind Goat opened, Tony introduced himself to the couple and the restaurateurs started commiserating on the labor-intensiveness of Vietnamese food. Tony offered to help prep at The Blind Goat so they wouldn’t have to take Christine’s egg rolls off the menu, and soon one conversation led to another. "We have similar backgrounds and it turns out, the same philosophy on Vietnamese food: our parent’s food is great, but we want to make it more contemporary and reflective of Houston," remarked Christine.

At Saigon House, Chef Tony Nguyen was known for his Viet-Cajun crawfish and his H-Town Bang sauce which contains 29 ingredients including garlic, butter, citrus, cayenne pepper and cilantro. It is now a weekly special at Xin Chao.

Photo by John Suh.

Within a few months, a location with a good deal on rent opened up and by January 2020, Christine, John, and Tony signed a lease for their new brick and mortar restaurant Xin Chao. “Going into business together is like a marriage, and we didn’t know each other that well, but you don’t know until you try.” Xin Chao would be a larger, more sophisticated restaurant than The Blind Goat, with a more robust modern Vietnamese menu complete with tequila and nước mía cocktails.

Local Houston artist Caroline Truong contributed on of the murals that cover the restaurant’s colorful interior and exterior. There is ample outdoor seating on bright blue picnic tables, a lifesaver considering Xin Chao didn’t open for business until September 2020 when America still had many pandemic restrictions for indoor dining. The inside consists of sleek wood tables, echoing the contemporary dishes.

Xin Chao Interior.

Photo by John Suh.

Speaking of their menu, the duo’s differing tastes result in a range of offerings. “Tony’s palette is very into robust flavors. He loves smoking meat and working with beef and pork. I am on the other end of the spectrum. I feel like less is more and when flavoring foods, I’m disciplined in creating a delicate balance. I enjoy creating more refreshing dishes and working with chicken and seafood,” analyzes Christine. And like any good marriage, “we complement and challenge each other.”

Xin Chao’s Smoked Beef Rib Flat Rice Noodles is one of the dishes that represent both Christina’s Texan side (smoked beef rib) and her Vietnamese side (flat rice noodles).

Photos by Tam Le.

You can find updates from Christine Ha, The Blind Goat, and Xin Chao on Instagram. You can also catch Christine Ha on a bag of Uncle Jax American Gourmet popcorn. As a notorious snack lover, I, Tam Le, will emphatically tell anyone who will listen and any readers of this article that Uncle Jax (either the Wisconsin cheddar cheese flavor or the Uncle Jax mix of cheese and caramel) is the best snack brand available in Vietnam.

Designed by Phan Nhi, Phuong Phan.

Top graphic by Jessie Tran.

Illustrations by Patty Yang, Hannah Hoang.

Ănthology is a series exploring stories of Vietnamese food served around the world. It focuses on chefs and restaurants that are reimagining Vietnamese cuisine or crafting traditional dishes in new contexts, and how our national dishes have evolved in response to different geographic tastes and ingredients. Have a good story to share? Let us know via contribute@saigoneer.com.