“These instruments serve our everyday life, or even our spiritual life. For example, they mark the transitions of life. When a baby is born or a person passes away, people play these instruments to welcome or bid farewell to these moments. They also use music to pray for good weather, good business, and happiness for future generations,” Đức Dậu, a seasoned collector of Vietnamese traditional instruments, shares how these antique musical devices are more than just merely tools used for entertainment.

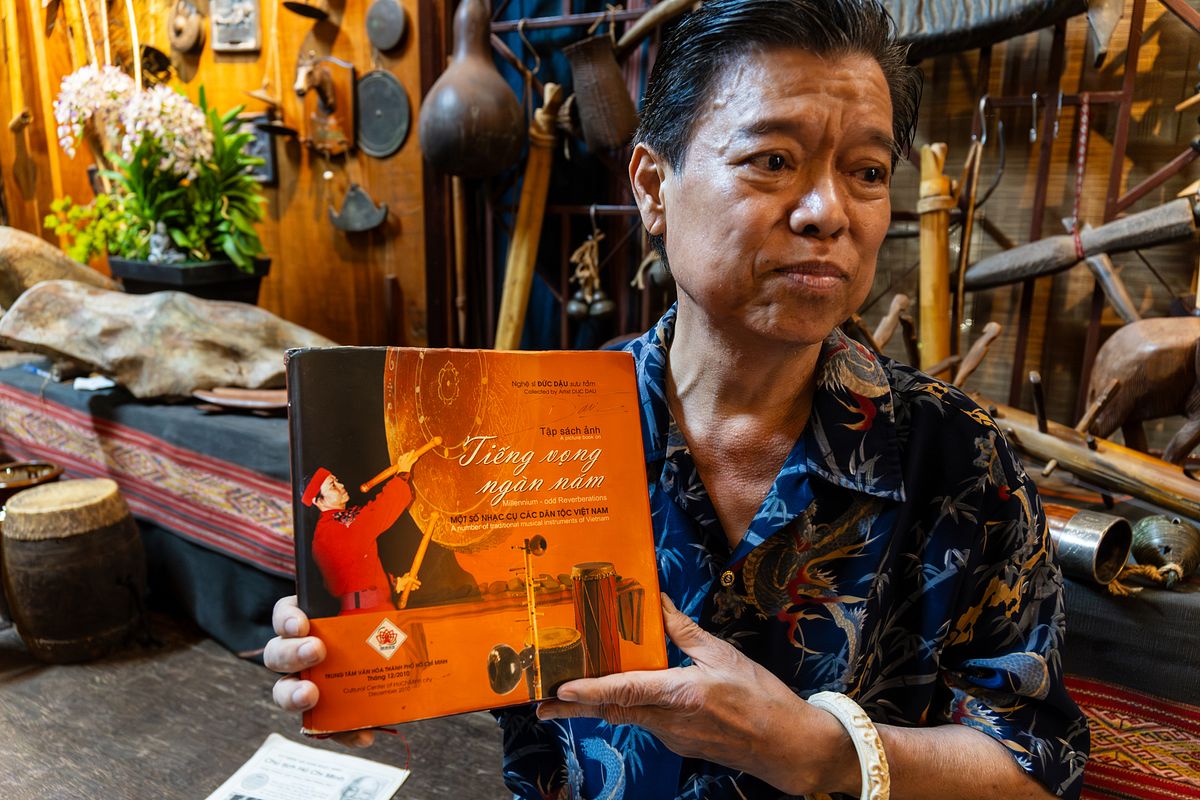

Dậu has dedicated more than 30 years of his life to researching and collecting musical instruments from Vietnam’s 54 ethnic groups. He garnered a massive collection of approximately 2,000 items from percussion to string instruments. He keeps them in his private home, a unique wooden house located in an alley off Phạm Huy Thông Street in Gò Vấp District.

Dậu’s residence is hard to miss as a large drum rests at the front of his property. Once one enters the home and closes the door, street noises disappear. The interior is adorned with stacks of century-old drums on one side of the wall, while on the other side there are hundreds of flutes, percussion, and other instruments on display.

Dậu is not only a collector but also a musician who uses these traditional instruments to make a living. Thus, “the arrangement of items here is not like a typical museum,” he explains. “Instead, they are arranged in such a way that I can pick up and use them on the spot.”

His bond with music began when he was just a child. Born in 1957, he lived on Hanoi’s Huế Street, right across from a theater. This provided him with “the sounds, the friction, and the artistic voices of cultural performers at the time,” he says.

Beyond the fortunate address, Dậu believes that his journey in music is predestined. His family are devout Buddhists, and initially, his father wanted him to pursue a career in medicine instead of music. However, during a funeral trip to Ba Vì District, Dậu’s father asked a monk for advice on his son’s future. The monk said: “No, your son’s fate is not meant to become a doctor, as he is meant to become an artist.”

During the 1970s, Dậu joined many local ensembles to make a living and hone his craft. In 1983, he joined the state’s Institute of Music and Dance Research in Hanoi and began collecting folk instruments. “I got the chance to learn from all the veterans, the experts in Vietnamese music culture. They were also researchers and collectors of these things too. So this collection of mine was inspired by my surroundings, my work and of course, it also came from my love for traditional music,” he explains.

In 1986, Dậu and his family relocated to Saigon, where he started his collecting journey. His time working at the research institute educated him about many traditional music festivals across the whole country, so he utilized his knowledge to visit those festivals and connect with local ethnic groups and communities.

But it wasn’t easy to actually get his hands on the instruments. “These artifacts are not just something that just money can buy, they were passed down from many generations. I usually ask the ethnic groups to help me learn about an instrument, how to play them, and their importance for their community. And in return, they either sell or gifted me the instrument out of appreciation,” Dậu shares.

Sometimes it takes up to four years of traveling back and forth from Saigon to the ethnic community area for Dậu to learn the ropes of playing an instrument and form a strong enough bond with the locals to ask them to sell it to him. “Sometimes I spent a lot of effort trying to get an instrument for my collection, but the locals ended up saying no. At those times I felt quite sad, but it is what it is, not everything is meant to be,” he says.

Dậu also attempts to purchase instruments that are no longer being made by the ethnic minorities or at risk of being dismantled for materials during difficult times as a way to prevent those artifacts from being lost in time. He wants to preserve the instruments, the stories behind them, how they were made and what roles they played in the community.

As we tour Dậu’s museum, he explains the mechanisms behind some artifacts. Materials such as wood, bamboo, leaves, or animal products are commonly used to craft traditional instruments.

The collection’s most notable instrument is a set of 300-year-old H'gơr drums from the Central Highlands region. They are played in Ê-đê ethnic minorities’ feasts such as a baby’s one-month anniversary, or a longevity ceremony. Made of wood and covered with elephant or buffalo skin, the drums seem immune to the effects of time. Dậu explains that the Ê-đê people had a special method to preserve these drums. “It is a secret recipe of their community. They use a type of leaf to mix into water, then the liquid is poured onto the drums, giving it a bitter taste so it doesn’t attract termites. Now you can see that 300 years later, it only gets old but not damaged.”

Dậu then offers to perform a song for us. “You need to hear the live sound of these instruments to somewhat feel the spirit of Vietnamese music,” he says. He introduces us to his chapi, a tube-shaped instrument that is often played during festivals in Kon Tum and Gia Lai provinces. It has 13 strings with a gourd shell attached to the end to amplify its echo.

Dậu started performing the song ‘Đôi Chân Trần’ (Barefoot), a song composed by people from the Central Highlands. The bright, up-tempo tune creates the adventurous atmosphere of embarking on a journey. Then Dậu begins to sing. The lyrics convey the perseverance and hardship of the Central Highlands people via the story of a man raising his child. Dậu’s rich, masculine voice alongside the chapi creates a full and powerful experience, despite it being a simple acoustic performance.

Dậu says that the location where a song is performed matters just as much as the instruments and performer. “These musical instruments are used in natural, mountainous areas. Therefore, I built a wooden house to somewhat preserve the sound, because bricks and concrete would not be able to convey the soul of the music. However, to have the genuine listening experience, you’ll have to go to each native place and see the locals perform,” Dậu says.

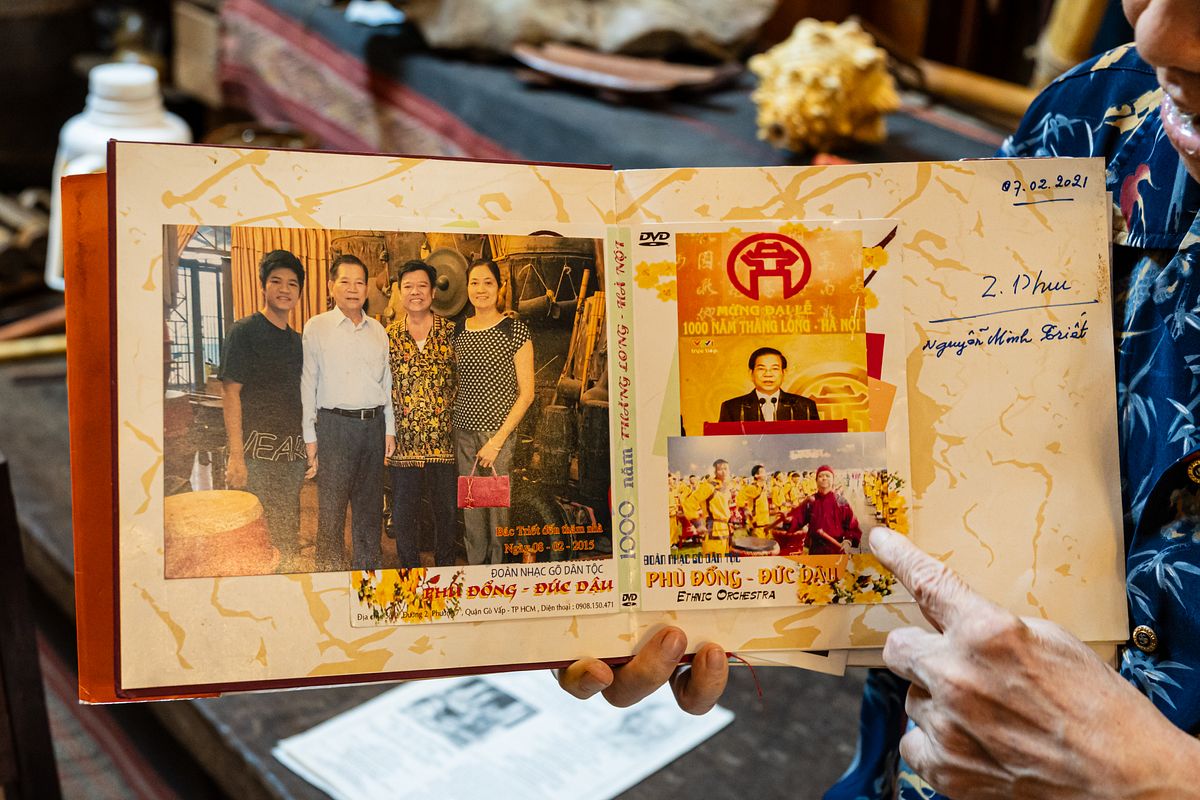

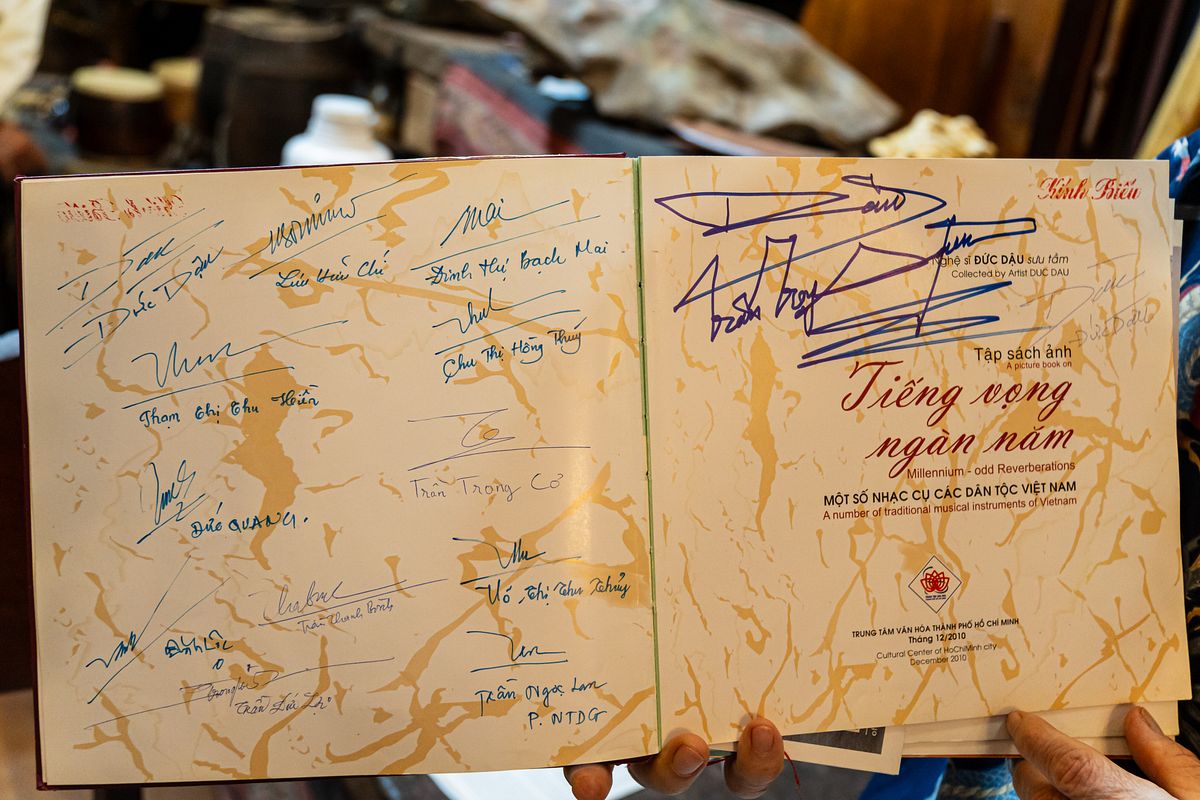

Dậu’s collection helps preserve people’s love and appreciation for traditional Vietnamese music. His large collection was documented for educational and research publications such as the photobook named Tiếng Vọng Ngàn Năm (The Thousand-Year Echo). In the 1980s, he formed a traditional music ensemble named Đoàn Nhạc gõ Phù Đổng with his family. Over the years, the Phù Đổng ensemble have shared their passion for traditional music with many schools, tourists, and festivals both in and outside of Vietnam.

“Fate has granted me the chance to preserve these artifacts, so I have to appreciate this opportunity and take responsibility for it. I want to bring this genre of music to more and more people, so that they can understand the cultural and spiritual values of traditional music,” Dậu says. “These instruments were made from natural materials granted by heaven and earth, and people used those blessings to craft the musical tools that serve their community. So the sound made by these instruments carries the Vietnamese identity, and with different communities and ethnic groups, you have the variations of melodies, rhythm, and symphonies,” he adds.

“In the past, there were people who offered me a crazy amount of money for this collection, but I refused. Because as I reflect on my collecting journey and my passion for music, these artifacts carry the soul of Vietnamese music, and no one can put a price onto them.”