Insects, pterosaurs, birds, and bats: flight evolved on Earth independently four times, so why do you think it’s so unlikely that you’ll find love again?

I used this reasoning to try and console a friend dealing with a break-up once. It didn’t go over too well, though I still consider it a rather insightful metaphor. One animal I didn’t list, however, was fish. Technically, fish have not learned how to fly. There is, however, an entire family known as flying fish (Exocoetidae), or cá chuồn, that comes deceitfully close.

Technically, fish have not learned how to fly.

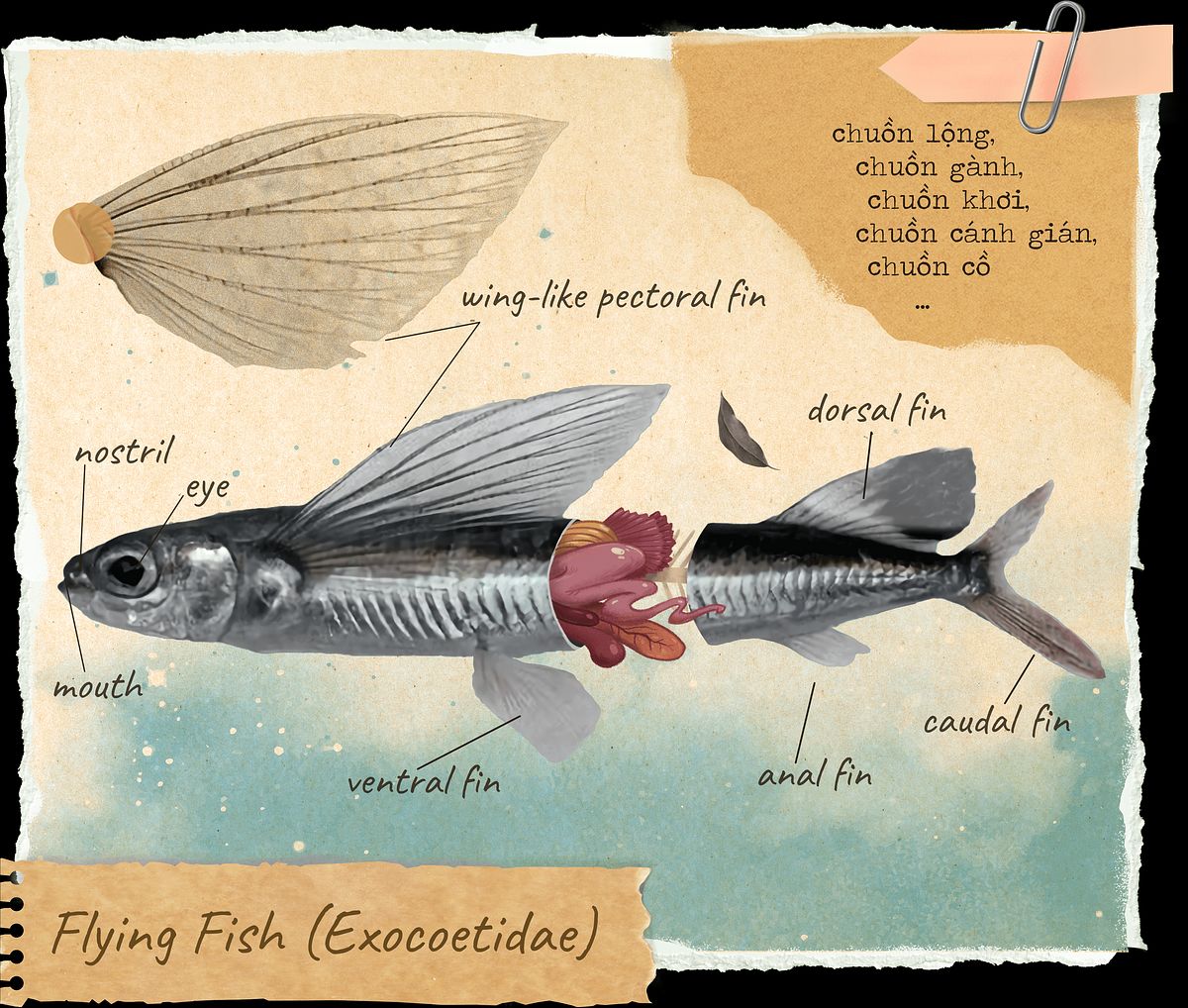

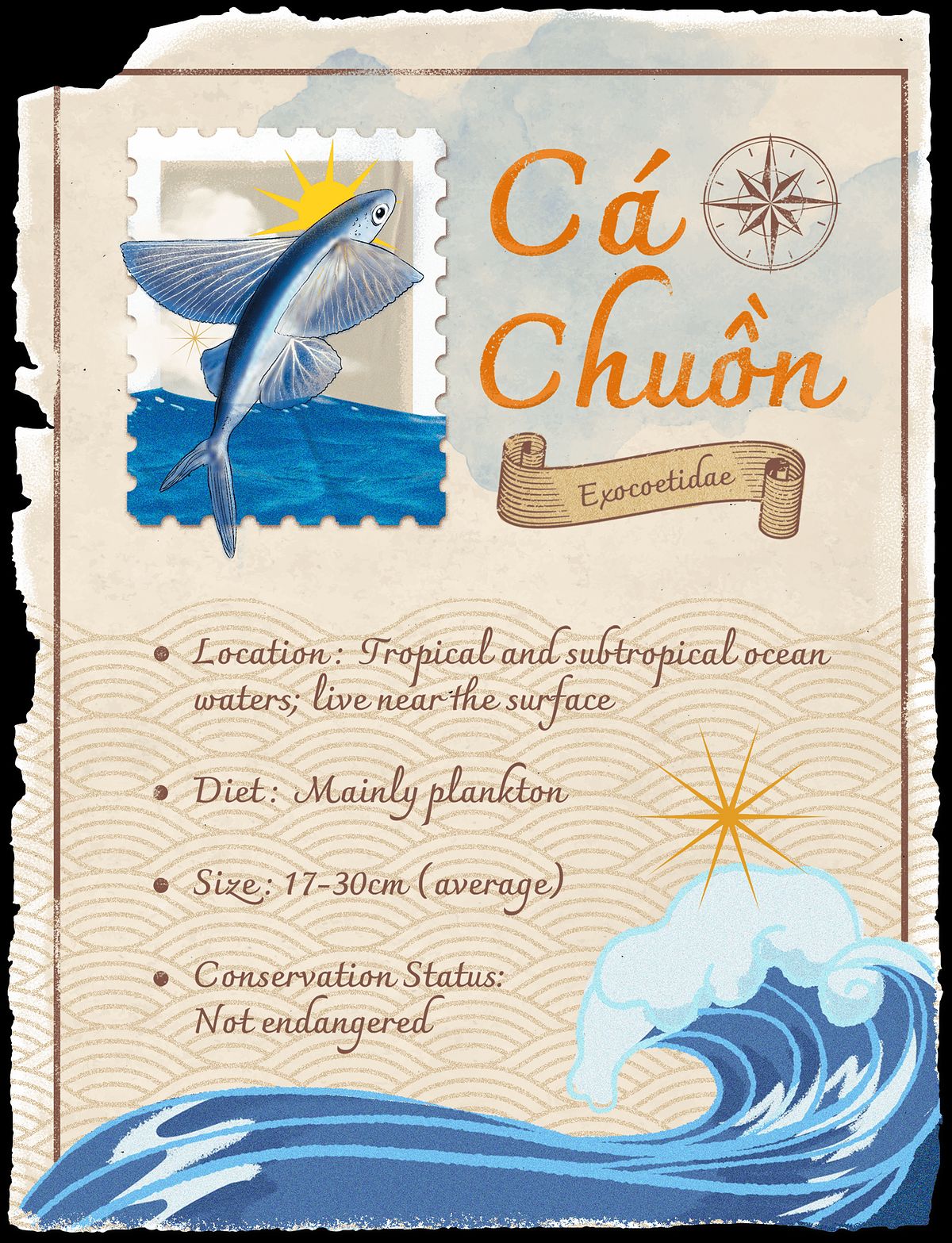

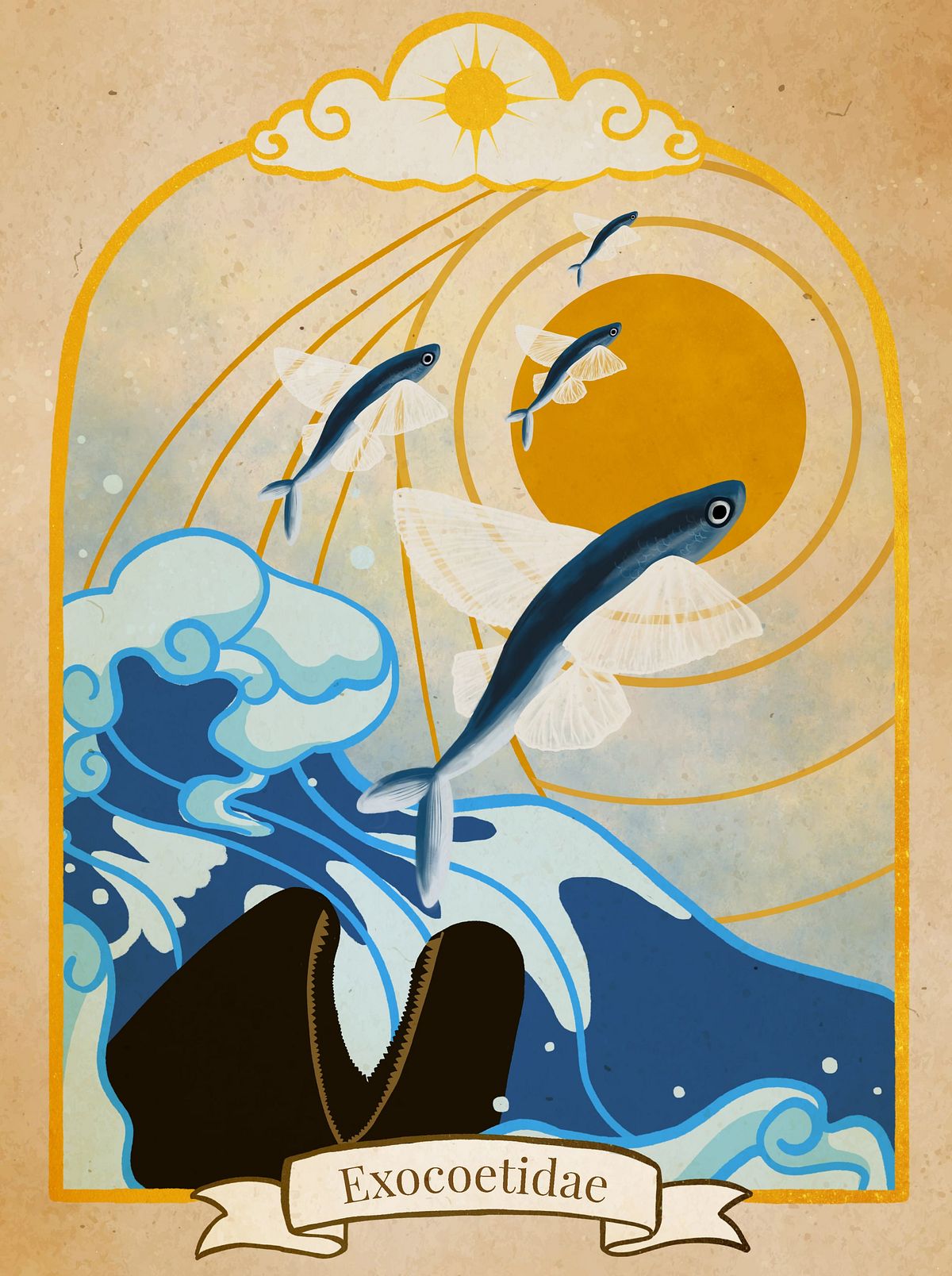

Approximately 64 species of cá chuồn roam each of the world’s oceans. Thanks to enlarged pectoral fins, and in some cases pelvic fins, and a rigid, strong spinal column with a uniquely shaped tail, after building up speed, they can break the ocean’s surface and glide for up to 200 meters for more than 30 seconds to evade predators such as dolphins, marlins and tuna pursuing them beneath the waves. When their iridescent wings unfurl and catch the sunlight, it’s easy to think you’ve seen the fish spontaneously transform into butterflies or scaled fairies.

Evolution, that drunken seamstress, has stitched together all sorts of strange creatures. From pistol shrimp that shoot superheated water bubbles to frogs that give birth through their mouths to the simple absurdity of a giraffe’s neck, natural selection has crafted some truly bizarre critters, so fish that can pseudo-fly are not that odd, really. And scientists have mostly sussed out the logical steps it took to go from small leaps above the surface to outmaneuver hunters to today’s extended gliding via slow and steady body modifications over hundreds of thousands of years of survival of the fittest.

Despite Darwinism’s many astonishments, it is highly unlikely that cá chuồn’s soaring will ever progress to true flight, though. After all, they cannot breathe air, have no feasible food source beyond sea-dwelling plankton and other small marine animals, and are at the mercy of more agile seabirds when airborne. This, however, shouldn’t cause any anger over their inaccurate name. After all, electric eels are not eels, red pandas are not pandas, and koalas are not bears. And the word flying is applied to species of squirrels, lemurs, snakes and lizards that, like cá chuồn, are simply long-distance gliders.

Cá chuồn are largely unheard of by inhabitants of most countries.

It’s not merely the sheer surprise of seeing a fish in false-flight that makes me enamored with cá chuồn, however. It’s also how relatively unknown they are. Much like cassowary, narwhal, axolotls, echidna, and capybara, cá chuồn are largely unheard of by inhabitants of most countries, despite their magnificence. Except, of course, in Barbados, where they are the national icon and appear on currency and passports, serve as an ingredient in the national dish, constitute a significant portion of the country’s economy, and have even resulted in tense stand-offs with neighboring nations over fishing rights. If nothing else, learning about the existence of cá chuồn reminds us of how magnificent the natural world is, and the pleasures offered by thinking beyond the scope of humanity once in a while.

But just because many people haven’t pictured a cá chuồn coasting above the sea, doesn’t mean they haven’t encountered them here in Vietnam. Several species, notably chuồn lộng, chuồn gành, chuồn khơi, chuồn cánh gián and chuồn cồ are caught in central Vietnam far off the coast in late spring using nets strung from the surface, or by placing lights in canoes that lure the fish to jump in. The catches then find their way to markets across the country via seafood wholesalers and even major ecommerce sites like Tiki.

When not unfurled for gliding, their fins don’t stand out, and they are sometimes removed after being caught, so if you see cá chuồn piled high in a vendor’s wicker basket you might not recognize them for what they are. But there is a chance you have eaten one, whether stuffed with turmeric and fried, braised with young jackfruit and green chili, or grilled with garlic. In the central region there is even a common song announcing the season when they are served: "Ai về nhắn với bạn nguồn / Mít non gửi xuống, cá chuồn gửi lên" (Whoever comes back, message me the source / Young jackfruit to you, flying fish for me).

they appear as miraculous dragonflies before melting like “snow-flakes as they touch the surface.”

Cá chuồn have found their way into English verse as well. In 1917, American poet Charles Wharton Stork penned ‘An Ode to Flying Fish.’ He praises the way they appear as miraculous dragonflies before melting like “snow-flakes as they touch the surface.” Plunged back into the dangerous depths, their flights are all too brief; but rather than become pessimistic about the plights of the flying fish, he concludes:

Yet joy it is! to scorn the dread of death,

To dwell for shining moments in the sun

Of Beauty and sweet Love, to drink one breath

Of a diviner element—though but one;

To reach a higher state

Of being, to explore a new domain;

To leap, and leap again,

Unheeding the gray menace of our fate

That follows till we fall:

For—fishes, men and all—

The grim old Shark will have us, soon or late.

Those brief moments of near-immortal exuberance are as much as any “poet, saint or lover” can hope for in life, he decides.

This brings me back to my attempt to console my friend over his broken heart. Perhaps I should have referenced flying fish after all. Cá chuồn can hope to remain in flight for only so long, I should have explained. But after they plummet into the frigid, merciless abyss, they can regather their strength, regain momentum and again break into the shimmering sunlight, savoring the splendors of the cool air. In this, they remind us it’s always possible to break free from our current situations and aspire to something greater, however brief it may be.

Graphics by Hannah Hoàng, Phan Nhi, and Hải Anh.

Animation by Phan Nhi.

Illustration by Hải Anh.

Photos by Steve N.G. Howell, Ross Robertson, and Hiroya Minakuchi.